Radburn, New Jersey and the Utopian Origins of the American Suburbs

Architects: Want to have your project featured? Showcase your work by uploading projects to Architizer and sign up for our inspirational newsletters.

When you hear the phrase “utopian design,” the images that arise in your mind are likely avant-garde. Perhaps you picture Buckminster Fuller’s floating spheres or, more contemporarily, the twisting glass towers and hovering drones of Telosa, a proposed city of 5 million that would be situated in the foothills of Appalachia. You likely do not picture a suburban cul-de-sac.

Today, the cul-de-sac seems utterly quotidian, especially in America, evoking images of placid tract housing. When I hear this word, I am imaginatively transported to Lake Park subdivision in Pewaukee, Wisconsin, where I lived from the ages of 6 to 9. Training wheels, sidewalk chalk, the smell of grilling bratwurst — these are the Proustian sensations that flood my mind. Nostalgic, maybe, but not utopian.

However, the cul-de-sac, like the subdivision itself, has its origins in utopian urban planning. Some of the earliest cul-de-sacs in America were built in the 1920s in the planned community of Radburn, New Jersey, a “Town for the Motor Age” constructed on the spinach fields of Bergen County, approximately 15 miles (24 kilometers) from midtown Manhattan. Developed by the City Housing Corporation and partially backed by John D. Rockefeller, Radburn received tremendous media attention when it was proposed in 1928 as one of the nation’s first centrally planned “garden cities.” Onlookers regarded the project as both novel and bold.

Aerial view of Radburn, New Jersey taken in 1935. Note how the homes are clustered close together. The narrow residential streets are cul de sacs — among the first to ever be built in America. This image was taken by the Farm Security Administration and is in the public domain as part of the Library of Congress collection.

Students of urbanism, especially Americans, are at this point waiting for the other shoe to drop. Planned communities, we are taught, are always failures. They seek, hubristically, to “organize freedom” and inevitably do not function as intended. We see the same thing time and again. Planned public spaces become neglected, often turning into hotbeds of crime.

While this might be a familiar story, it is not Radburn’s story. An incorporated community in the borough of Fair Lawn, Radburn’s layout really does function as intended. Pedestrians make ample use of the footpaths, which are refreshingly insulated from the constant buzz of traffic that characterizes life in Bergen County. I’m not sure this community manifests utopia, but it is a place its residents take pride in.

I first learned about Radburn a few years ago when I moved to Bergen County from Manhattan. I was on a playground, pushing my son on the swing next to another parent who spoke effusively about her 1920s subdivision with “no backyards, just a shared courtyard.” In Radburn, I learned, residents can walk to the local shopping center and school without needing to cross the street. As someone who was struck by cars multiple times as a distracted adolescent, I was envious.

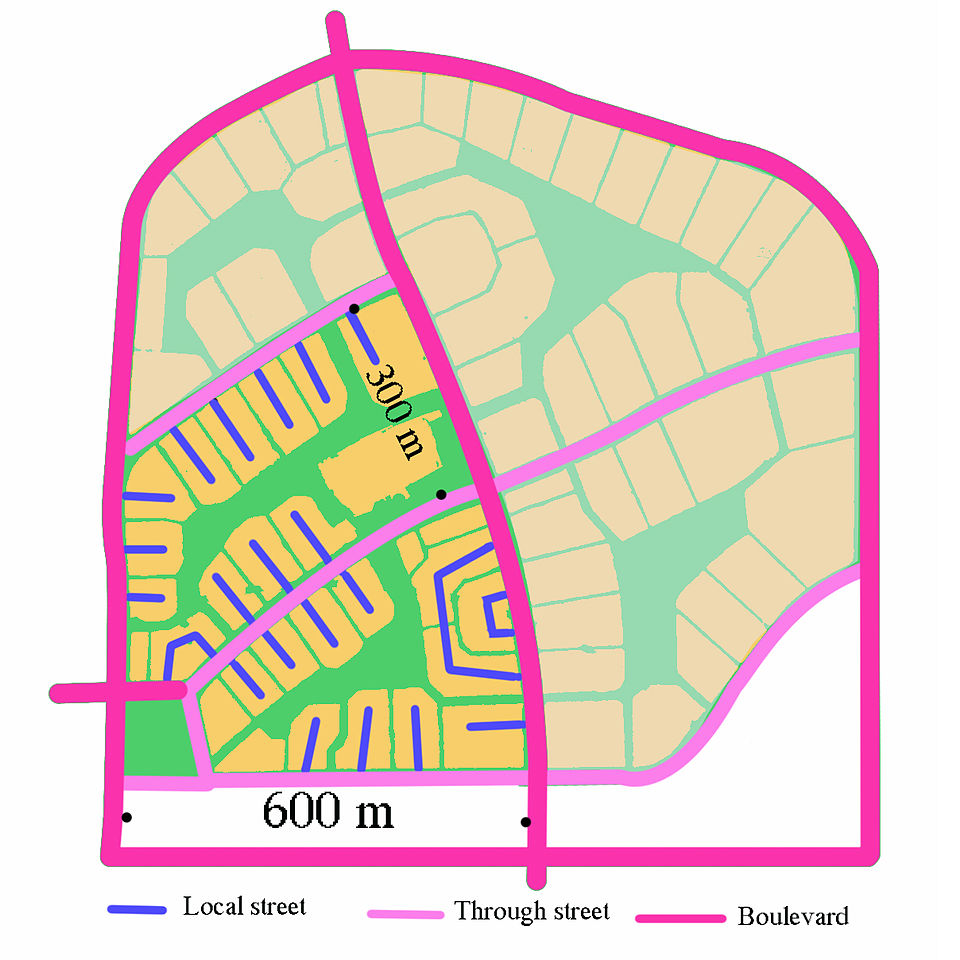

A diagram of Radburn’s layout. The shaded area was not built. The shared green spaces in between the superblocks — Radburn A and B — are protected from the roads and lined with pedestrian walkways. Image by Fgrammen, CC0, marked public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Looking more closely into Radburn, I was able to wrap my mind around the layout. Essentially, the neighborhood is organized into superblocks with the backs of houses facing onto a public park crossed by pedestrian paths. There are really two parks, Radburn A and Radburn B, but they are contiguous. Residents access their homes by car by turning into the famous cul-de-sacs, among the first ever built in the U.S. (Some say this cul-de-sac in Buffalo is the actual first one). By Jersey standards, the lots and homes are relatively small, giving the neighborhood an intimate feel. There are a blend of freestanding homes, townhomes and apartment buildings and the predominant architectural styles are unassuming and quaint, mostly Tudor and Colonial typologies. While this is a centrally planned community, there is enough variety to offset the homogenous feel that so many similar developments suffer from.

In a 1930 article in the journal “Landscape Architecture,” Radburn’s landscape architect Marjorie Sewell Cautley explains the key features of her proposal: “In the first place, there are no backyards. Instead, living rooms and porches open directly into little lawns and garden areas, and through the center of each group of gardens a walk leads safely to the park. The effect is quite the reverse of that on the street side: from every porch there is an extended view, across garden plots and flowering hedges, to the park beyond, a view which can never be spoiled by some neighbor’s garage or service wing, for these were so placed in the beginning to preserve that very view. Again the houses that seemed most shut in at the end of the short residence streets are the very ones which enjoy the greatest space and the most extended views up and down the parks.”

The picturesque scene Cautley described is still accurate today, almost 100 years later. The parks are likely even more beautiful than they were then, as the trees that Cautley planted have reached maturity. But what sets Radburn apart from other suburban neighborhoods is its livability. Several well-known Fair Lawn businesses are housed within the Radburn Plaza building, recognizable by its iconic clock tower. This building, which experienced significant fire damage several years ago, has since been carefully restored to its original appearance. Close by is the Old Dutch House, a historic tavern dating back to the era when the area was a Dutch colony. Opposite the Plaza Building stands the Radburn railroad station, which continues to serve passengers today via New Jersey Transit’s Bergen County Line. Finally there is The Radburn School, an Elementary School situated on the edge of the “B” park. To me, this is the coolest part of Radburn — the fact that kids can get to school without having to cross the street.

A Radburn cul-de-sac. It might seem commonplace now, but at the time these types of streets were unknown in America. The real magic of Radburn, however, is visible behind the houses, where small lawns open onto the shared green space. | Dmadeo, Radburn-cul-de-sac, CC BY-SA 4.0

Currently, 3,100 people live in Radburn. A townhouse development is currently under construction that will expand the community somewhat, but it is still far from the original proposal, which was meant to house 30,000. Like many other building projects of the 1930s, Radburn’s growth was stalled by the Great Depression.

Radburn’s success led to a new paradigm of building called Radburn design housing, in which residences are created to face onto a shared courtyard rather than the road. Many such developments were created all around the world, from Los Angeles to the UK to Australia. However, the majority were not as successful as the original. Like many other types of centrally planned communities or “projects,” Radburn style estates became hotbeds of crime. Urbanists, echoing Jane Jacobs’ critique of planned developments of all kinds (she specifically criticizes Radburn in The Death and Life of Great American Cities), blame the fact these communities are cut off from the surrounding urban fabric. Like awkward little islands, they are unable to flexibly adapt to new changes and are thus less resilient than urban areas that have not been centrally planned. In a 1998 interview, the architect responsible for introducing the Radburn paradigm to public housing in New South Wales, Australia, Philip Cox, spoke regretfully about a Radburn-designed estate in the suburb of Villawood: “Everything that could go wrong in a society went wrong…. It became the centre of drugs, it became the centre of violence and, eventually, the police refused to go into it. It was hell.”

A blogger for the website “Here and Now” who goes by the alias “The Urban Idiot” provides this analysis of Radburn’s influence in the UK: “As with many brilliant ideas, a layout developed for the middle classes in New Jersey didn’t work quite as well for a council estate on the outskirts on Hull. Radburn estates in the UK looked very different to the leafy streets of the original. They were built for council tenants, at high densities but also contained an additional refinement that guaranteed that they would never work. Whereas the houses in the original Radburn faced onto the street, British planners decided to turn them around so that they fronted onto the pedestrian network with cars relegated to rear parking courts. Anyone who has spent any time on a Radburn estate in the UK will know what a disaster this was. Residents no longer understood which was the private side of their home, indeed everything became public. Cars parked beyond high ‘rear’ garden fences were vulnerable to crime while the pedestrian walkways at the ‘front’ were deserted and dangerous. Overall the layouts became convoluted and confused, making them impossible to police and turning them into no-go areas for anyone who didn’t live there.”

In 1964 Radburn, N.J., was featured in a public television program, “The Rise of the New Towns.’’ The clip here depicts “the town for the motor age’’ in the late 1930s and in the early 1960s. The ‘30s footage is from The City, a documentary made for the 1939 New York World’s Fair. The ‘60s scenes seem to have been shot specially for the program in 1964 that aired on WNET.

So what is the deal? Is central planning at fault? In my view, only partly. For sure, bad planning — schemes that isolate communities and make work and shopping less accessible for residents — can magnify existing social problems. But it doesn’t cause them. By the same token, good planning, taken by itself, cannot solve deep rooted problems such as inequality. The biggest issue with the Radburn estates in the UK wasn’t the pedestrian courtyards, it was that they split low income residents from the rest of the city. Mixed-income superblocks would have worked out very differently.

The story of Radburn is one of hope. Clarence Stein, Henry Wright, and Marjorie Sewell Cautley all shared the belief that people in the future would live better, more dignified lives than people did in their own times. Observing a society of crowded tenements, they designed garden cities. While there are no perfect solutions for an imperfect world, the problem of providing the best housing for the most people is one that continues to demand the attention not only of architects, but people at all levels of society. In this task, the failures of Radburn are as instructive as its triumphs

Architects: Want to have your project featured? Showcase your work by uploading projects to Architizer and sign up for our inspirational newsletters.

Cover Image: Radburn, NJ in 2001. Image via Design for Health, CC By 2.0.

The post Radburn, New Jersey and the Utopian Origins of the American Suburbs appeared first on Journal.