Set-Jetting: How Film Tourism is Changing Real-World Landmarks

Fans are turning film sets into must-visit destinations and, in the process, are reshaping cities, architecture and even regulations. The post Set-Jetting: How Film Tourism is Changing Real-World Landmarks appeared first on Journal.

Architects: Want to have your project featured? Showcase your work through Architizer and sign up for our inspirational newsletters.

At some point in the last decade, the idea of a “cultural pilgrimage” has shifted from tours of cathedrals in Europe and exploring ancient ruins in Asia to snapping a selfie outside that particular brownstone in New York or running full speed up a certain set of museum steps in Philadelphia.

Every day, sites around the world are flooded with visitors who, thanks to their portrayal in TV shows and movies, are more interested in a landmark’s on-screen role than the true history of the architecture. The medieval streets of Dubrovnik have been recast as King’s Landing, Matamata in New Zealand has been known as Hobbiton since the early 2000s, and in Albuquerque, the owners of a perfectly ordinary family home have had to install a fence, not for security but to deter Breaking Bad fans from lobbing pizzas onto their roof.

It’s a phenomenon that is changing urban landscapes and, in some cases, requiring quite extensive intervention.

Unlike traditional tourism, which at its core is cultural appreciation, film-induced travel, otherwise known as “set-jetting,” is obsessively specific. It doesn’t focus on a certain city or a period of history with broad geographical bearings. A single storyline, character or shot is what is important to fans. They want to stand in the exact spot where their favourite character was triumphantly victorious or mercilessly executed. In the process, they’ve arrived in droves and altered the significance of these singular places, creating shrines of pop culture.

Highclere Castle, United Kingdom | Photo by leefenn-tripp via Pixabay.

For some locations, it’s a financial lifeline, pouring fresh revenue into a building that might otherwise be in disrepair. For others, it becomes more of a burden than a blessing. For better or worse, film-induced tourism has become a global sensation. As streaming services flood our screens with expansive universes, fans increasingly want to walk in the footsteps of their favourite fiction.

Yet it isn’t merely the novelty of fans running around in cloaks or brandishing plastic swords that makes fan pilgrimages great. On a deeper level, these pilgrimages are changing the way in which entire communities and their architecture survive.

For some buildings, cinematic fame provides a second life by injecting huge amounts of revenue. If Highclere Castle, the grand 19th-century estate immortalized as Downton Abbey, had relied solely on heritage grants and private funding, it might have suffered the same fate as countless stately homes across Great Britain. Partial closure, dwindling maintenance or an ignoble transformation into a corporate events venue is a story told year in and year out.

Instead, since the show’s debut, the estate has welcomed over 120,000 visitors a year, pouring revenue into much-needed roof repairs and historically accurate conservation work that might otherwise have been impossible. In the decade since Downton Abbey first aired, ticketed tours and spin-off events have funded repairs on over 50 rooms, helping the estate maintain its integrity without compromising its history. A similar story unfolded with the Hatley Castle in Canada, a popular film location for over 80 years. See X-Men and Deadpool as recent examples.

Dubrovnik, Croatia | Photo by Ioannis Ioannidis via Pixabay.

However, for locations with genuine architectural or historical significance, film tourism can be a double-edged sword. The streets of Dubrovnik, now synonymous with Game of Thrones, have seen an explosion in foot traffic, with over 4 million overnight stays recorded in 2019 — double the numbers from 2012, when the series first aired. The historic limestone streets, some over 700 years old, have suffered serious erosion under the weight of tourists, leading UNESCO to recommend stricter visitor management strategies.

In cases like this, preservation authorities struggle with a fundamental question: should a site continue to be protected for its actual history, or should it evolve to accommodate the identity given to it by popular culture? The latter isn’t as absurd as it sounds. After all, heritage is often shaped by perception as much as fact. The difference is that in traditional historic preservation, the narrative is that of real events. With film tourism, it is dictated by a storyline that has no direct connection to the site itself.

Skellig Michael, County Kerry, Ireland | Photo by NakNakNak via Pixabay

In truth, some places simply weren’t designed to handle their newfound popularity. Skellig Michael, a 6th-century monastic settlement off the Irish coast, saw visitor numbers surge from 11,000 to 17,000 annually after its role in Star Wars: The Last Jedi. While its dry-stone beehive huts have withstood centuries of Atlantic storms, they are far more vulnerable to human impact. The narrow stairways, never intended for large crowds, face accelerated erosion, prompting conservation authorities to also introduce strict visitor caps and controlled access points.

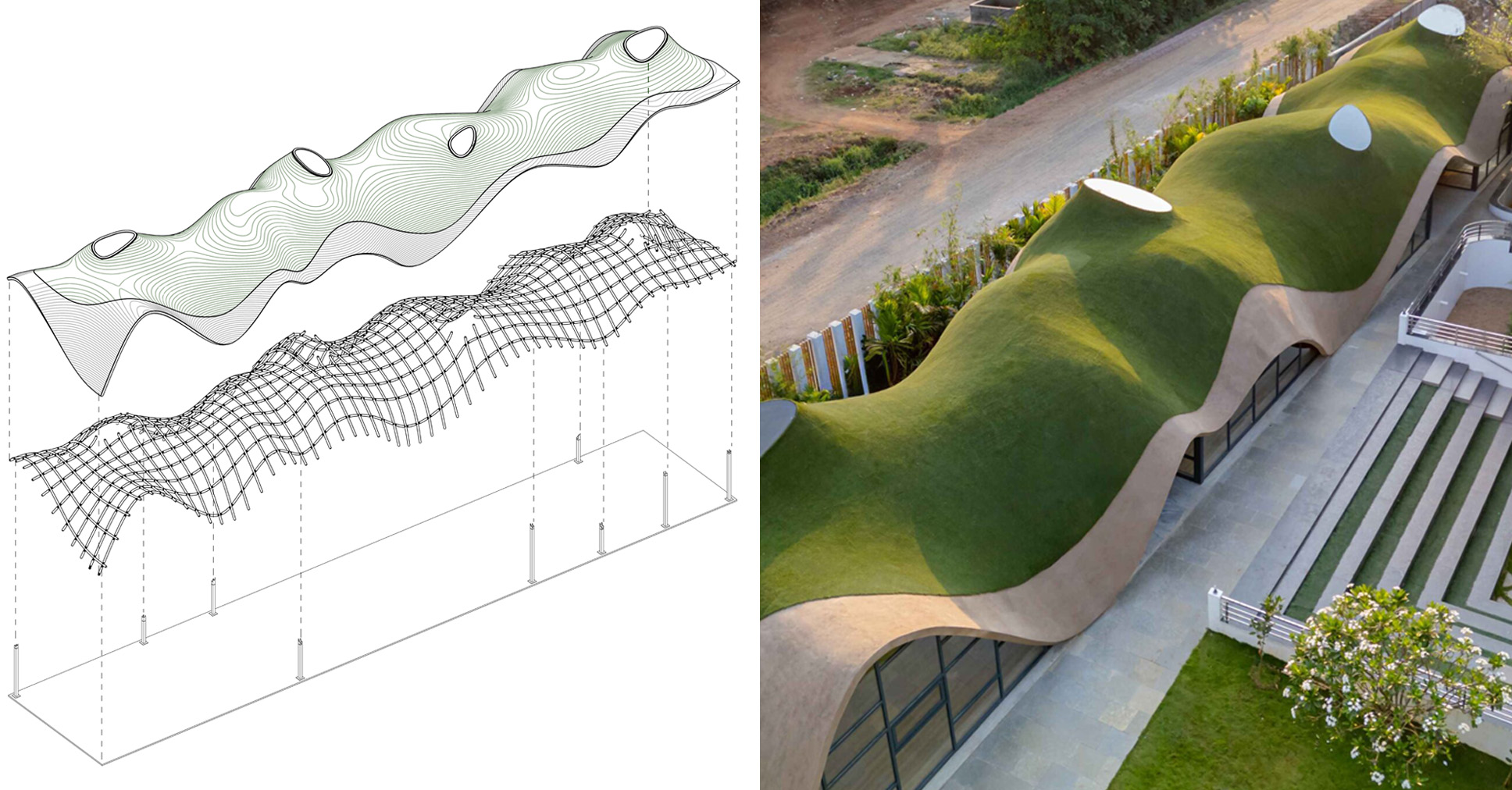

The architectural imprint of film tourism doesn’t just affect existing buildings either. It influences future development. In cities eager to capitalize on cinematic fame, new projects have been seen to take design cues from fictional worlds, ultimately reshaping the architectural vernacular of a place.

Tribune Tower Conversion by SCB, Chicago, Illinois

For instance, Chicago’s postmodern skyline has played the role of Gotham City many times, with Christopher Nolan’s Dark Knight trilogy using the city’s real streets and skyscrapers to depict Batman’s cinematic world. In the years following, multiple new high-rise developments have adopted darker glass façades and angular silhouettes, mimicking the aesthetics of Gotham’s on-screen identity. Whether deliberate or not, film-driven perception feeds back into the real world, influencing design choices in profound ways.

Hotel Marcel by Becker + Becker, New Haven, Connecticut

Likewise, on a broader scale, the revival of Brutalism in contemporary architecture can, in part, be attributed to shifting cultural feelings about the style that everyone once hated. Once regarded as ugly relics, the worst of mid-century design, the stark, imposing concrete structures have become essential backdrops for dystopian productions. Andor, The Last of Us and even Blad Runner 2049 all adopt a brutalist aesthetic, making it popular once more. This renewed visibility has fuelled a growing appreciation for Brutalist icons, recognizing them as sought-after cinematic settings.

In most cases of popularity as a result of set-jetting, the challenge lies in finding a balance between welcoming the cultural and economic benefits without sacrificing architectural integrity. For some, this means enforcing crowd management strategies for protection. In others, it might involve leaning into a site’s newfound cinematic legacy and using it as a means of reinvention. The most sustainable approach is one that acknowledges that a building can be both historically significant and culturally redefined and that architecture can exist in a state of continuous reinterpretation without losing its core identity. Architects: Want to have your project featured? Showcase your work through Architizer and sign up for our inspirational newsletters.

Top image: Hobbiton in New Zealand by hunt-er via Pixabay

The post Set-Jetting: How Film Tourism is Changing Real-World Landmarks appeared first on Journal.