Montessori for Millennials: Architecture That Lets Adults Choose

Got a project that’s too bold to build? Submit your conceptual works, images and ideas for global recognition and print publication in the 2025 Vision Awards, launching this spring! Stay updated by clicking here.

Walk into a Montessori classroom, and you won’t find a front and a back. There will probably be no whiteboard wall and, certainly, no teacher’s desk monopolizing a fifth of the space. Instead, the area is open. All of the furniture, fixtures and fittings are low to the ground, and nothing’s hidden. Shelves are shallow. Cupboards are nonexistent. Tools are visible and within reach. Young people are taught that they are free to move between zones and subjects at will, without the need for permission. These are usually calm spaces, not controlling ones. And they are very deliberately designed that way.

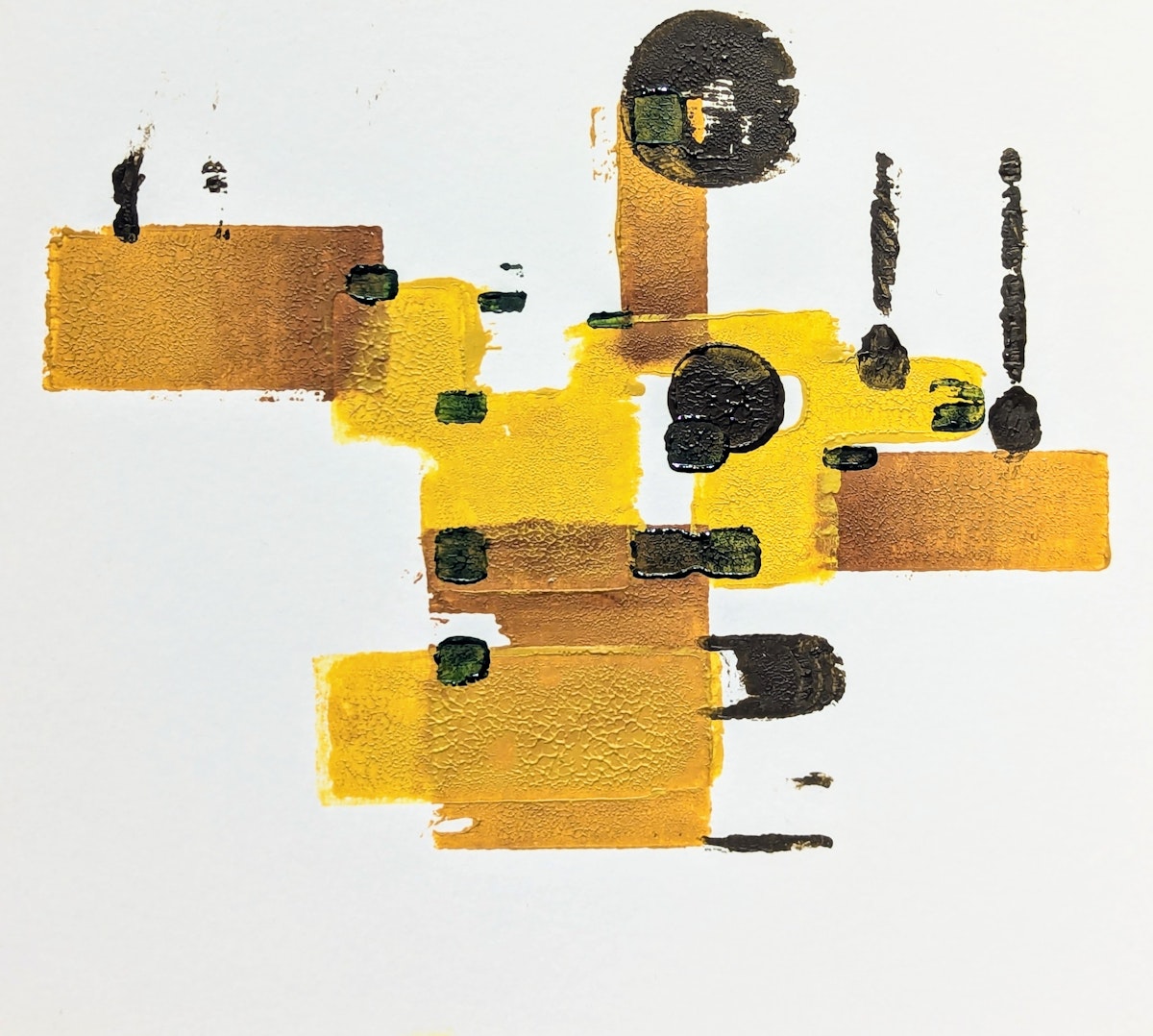

The idea that spatial design can guide behavior without dictating it is something interior designers and architects have pondered and played with for centuries. But usually to serve a goal set by the client or designer — more footfall over here, less lingering over there. Montessori, by contrast, is about encouraging individual thought and independent decision-making. The space isn’t guiding people toward an outcome. It simply makes sure they can get there themselves.

123+ Kindergarten by OfficeOffCourse, Shanghai, China | Photos by Li Huang

Maria Montessori wasn’t a teacher by training. She was Italy’s first recognized female doctor, with a background in medicine, anthropology and biology. Her method was developed through direct observation, paired with structured tools she called “didactic materials” — physical objects designed to teach through repetition and touch. In the early 1900s, she began working with children from working-class families and those considered intellectually disabled. Groups who, at the time, were excluded from mainstream education. What she noticed, quickly and clearly, was that most classrooms were designed not to support children but to control them. Rows of desks. Single points of instruction. Environments built for discipline, not curiosity.

She thought there was a better way. Instead of ordering children to pay attention, she changed the environment so that they could choose what to focus on. The room was broken into zones. The furniture was light and scaled to the user. Materials were out in the open, not locked away. If something spilled, it got cleaned up. If a child was ready to move on, they didn’t have to ask. The room told them what was possible. They just had to decide what to do.

AKN Nursery by HIBINOSEKKEI+youjinoshiro, Akiruno, Japan | Photos by Studio Bauhaus

It was a complete rethinking of what a learning space could be, and it’s still in use today. The Montessori classroom isn’t a stage for a tutor to perform. It’s a system of layout, scale and logic that individuals can inhabit in the way that suits them best. Every detail is considered, from the height of the chair and the depth of the shelf to the visibility of the tools available—not for aesthetics but for usability. Not to control the child but to give them autonomy.

Fast forward a century, and interestingly, most millennials are only now starting to experience the kind of spatial autonomy that Montessori built into her classrooms from day one. Most of us grew up with national curriculums, rigid lesson plans and carpet squares for assembly, and once we joined the workforce, the message stayed the same: follow the system, stick to the schedule, and keep to your lane. The idea of designing your own rhythm or setting your own pace was treated as an exception, not the norm.

Roche Multifunctional Workspace Building by Christ & Gantenbein, Grenzach-Wyhlen, Germany | Photos by Walter Mair

However, the pandemic upended routines and exposed how fragile those top-down systems really are. Almost overnight, the workplace lost its center. People started working from bedrooms and kitchen tables, and eventually from anywhere they wanted. Some returned to the office. Many didn’t. Others left entirely and took to the freelance way of life. Whatever the path, the result was much the same. People began rethinking how their lives should be structured — and who should be the one making the decisions.

It’s a clear shift in psychology. When Gallup started surveying workers post-2020, a consistent pattern emerged: autonomy wasn’t just preferred, it was directly linked to engagement and performance. In parallel, environmental psychology has shown that people respond better, both mentally and physically, when they feel a sense of control over their surroundings.

Now, five years on, you can see the change developing across the wider built environment, not just in our homes and offices but in all sorts of places where, not long ago, architecture was more interested in instruction than invitation.

Minneapolis Public Service Building by Henning Larsen, Minneapolis, Minnesota | Photos by Corey Gaffer

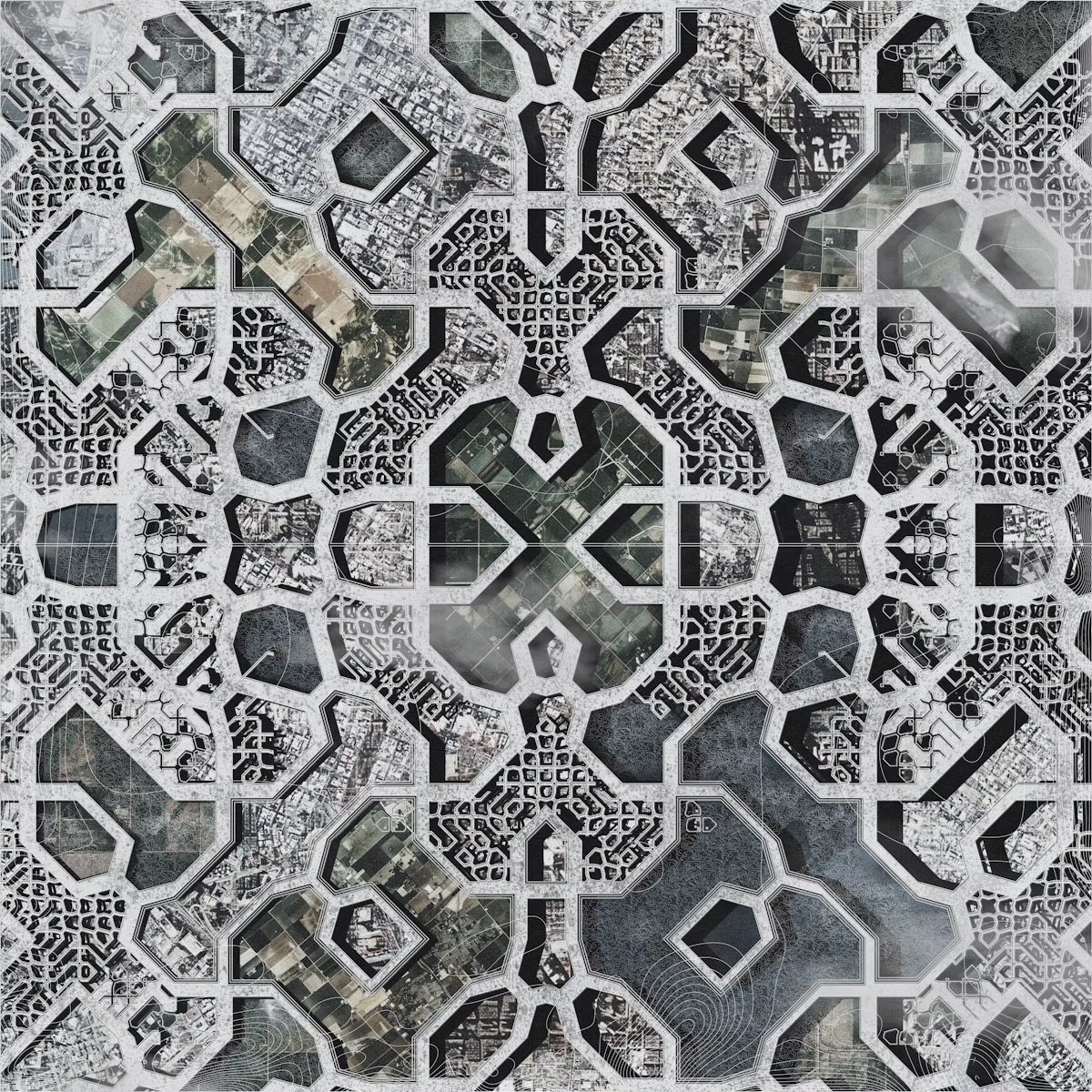

Take public buildings. The biggest change is in how people move through them. You used to enter a civic building and know exactly where you were meant to go. There was usually a big color-coded sign, maybe a map if you were lucky, to direct you. Now you’re more likely to find buildings laid out like frameworks rather than floor plans. No single route through. No strict zoning. Rooms aren’t named. Boundaries are suggested by a shift in floor finish, a change in light, or the way furniture sits in space. You’re given just enough to make sense of it and then you’re left to get on with it.

In cultural buildings, flexibility has become paramount, but not in the usual sense. It’s more about leaving interpretation open. A stair landing can be a reading spot. A window bench becomes an individual research center; we see more people sitting on the floor against a wall because that’s where they feel most comfortable. Some of the best new projects have stepped away from over-programming. They let their visitors give meaning to a space through its use, not by dictating with signage. Architects are getting more comfortable with that ambiguity. They’re designing areas that can absorb different types of behavior without collapsing into a mess. There’s real skill in that.

The Pitch by Mark Odom Studio, Austin, Texas | Photos by Casey Dunn

Across hospitality, we’ve seen this happening for a while. Probably longer than most industries. The hierarchy’s gone soft. The goal isn’t to lead the guest through a series of predetermined experiences — lobby, host, table, bar, exit. Now, the idea is to create an environment that supports different kinds of interaction without over-orchestrating them. Different guests want different experiences, and to be successful, you’ve got to find out how to facilitate that. There’s more variety in seating. More fluidity between the front and back of the house. You might be ten feet from the kitchen, or perched somewhere no one needs to find you. The space, and therefore the staff occupying the space, doesn’t assume everyone wants the same thing from it. And that’s the point.

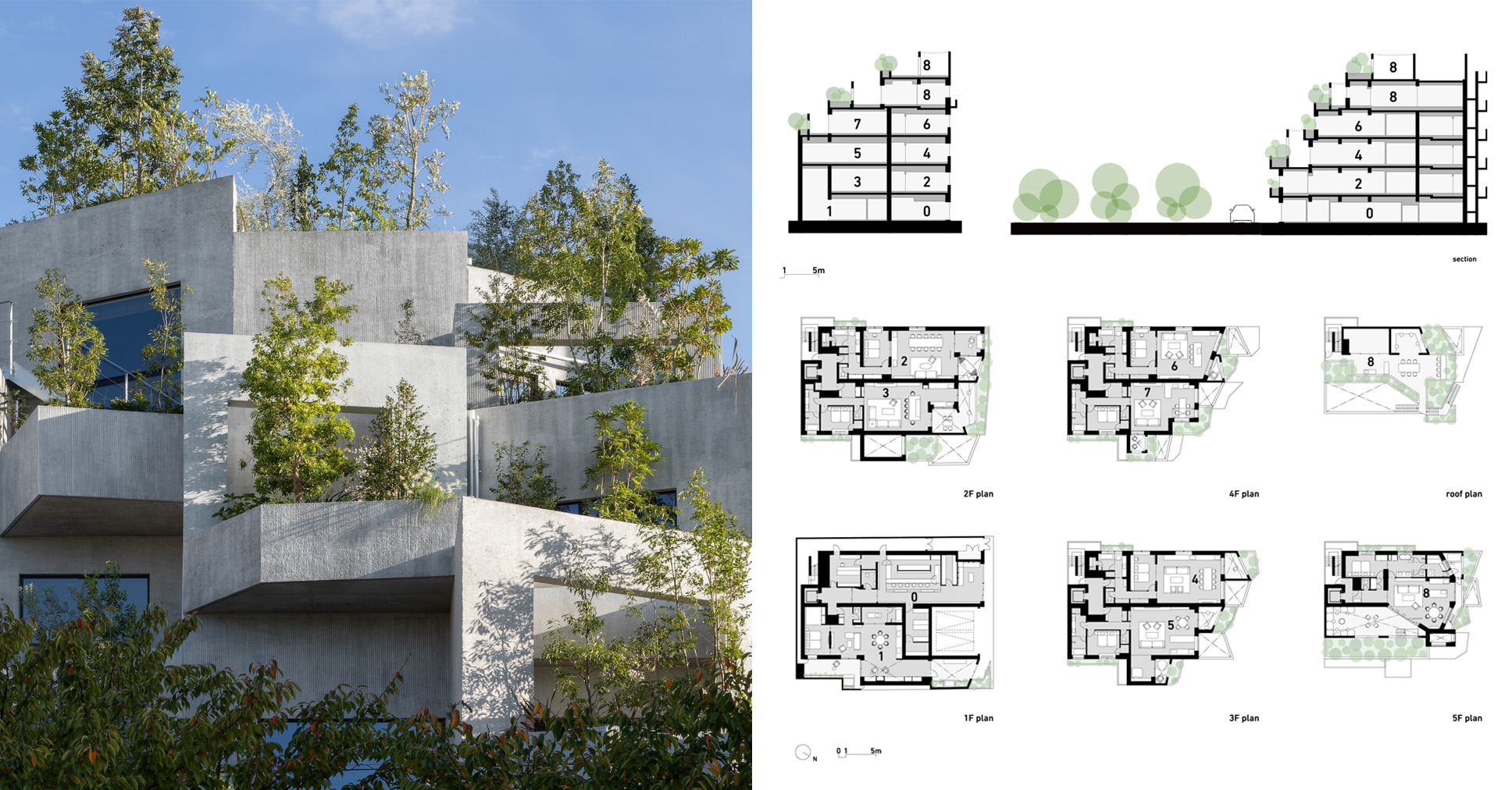

In housing, open-plan layouts aren’t enough, but rooms doing five things at once is way too much. What’s changing is the underlying assumption that each room within our homes has a job, and people are there to fulfill it. Instead, architects are starting to design for potential, not prescription. You get joinery that defines but doesn’t divide. Slight changes in level. Shifts in material. Lighting that nudges one way or another. There’s structure, but it’s light-touch. The space doesn’t care how you use it, just that you can — and do.

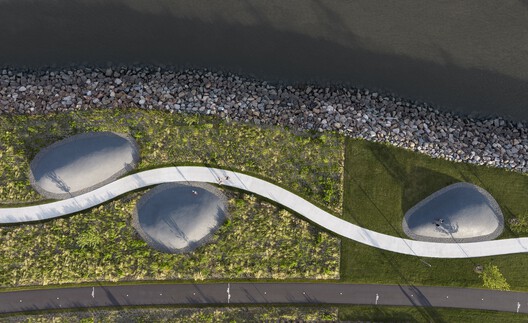

Tom Lee Park by Studio Gang, Memphis, Tennesee | Photos by Tom Harris

Even in the public realm, this Montessori thinking is filtering through. The most effective urban inserts aren’t grand or didactic. They’re simple yet highly effective. It could be a broad step that’s also a seat. A covered corner that might be for waiting, chatting, sheltering or even performing. It’s low-cost, high-agency stuff. The design doesn’t tell you what to do. It gives you just enough of a framework to do something.

Across all of these industries, the same change is playing out. Architects are designing less for function and more for use. This, of course, sounds obvious until you realize how many buildings are still laid out like factories. Trafficking us from one station to the next. Maria Montessori didn’t just build flexible classrooms. She built systems that supported autonomy. And now, the rest of the world is, too.

Got a project that’s too bold to build? Submit your conceptual works, images and ideas for global recognition and print publication in the 2025 Vision Awards, launching this spring! Stay updated by clicking here.

The post Montessori for Millennials: Architecture That Lets Adults Choose appeared first on Journal.