Design Won’t Save Us — But We Need It: Inside the Triennale di Milano’s Blockbuster Exhibition, “Inequalities”

The winners of the 13th Architizer A+Awards have been announced! Looking ahead to next season? Stay up to date by subscribing to our A+Awards Newsletter.

In a recent article about the legacy of “garden cities” and other planned housing developments, I wrote that “[design], taken by itself, cannot solve deeply rooted social problems such as inequality.” Admittedly, the phrase “taken by itself” does a lot of work here, and I fear my point might have been lost. To be clear, architects, urban planners, and designers of all kinds, of course, play an essential role in addressing social problems. They have the same role all artists do, which is to open up new ways of thinking and seeing. While design can’t solve problems like inequality, designers can point new ways forward by questioning prevailing premises and offering provocations. As the literary critic Viktor Shklovsky said of literary writers, designers can “make the familiar strange so that it can be freshly perceived.”

The “Shklovsky standard” is the main criterion I use to evaluate speculative design projects like those featured in the current International Exhibition at the Triennale Milano, “Inequalities.” The 24th edition of the Triennale’s Internal Exhibition, which has been running since 1923, Inequalities “examines the issue of disparities through 10 exhibitions, 8 special projects, 20 international participations, installations, and events that share global visions, urgencies, and perspectives.” The show has been described as the final entry in a trilogy of highly meta exhibitions that began with “Broken Nature” (2019), which explored environmental destruction, and “Unknown Unknowns” (2022), which speculated on the cosmos.

The Triennale di Milano is the premier design museum in Italy’s design capital. Since 1923, the museum has intermittently hosted an “International Exhibition” showcasing work from artists and designers around the world. This year’s edition, the 24th, explores the theme of inequality. The museum is housed in the magnificent Palazzo Dell’Arte, a masterpiece of Italian modernism that also has an uncomfortable fascist past due to the political leanings of its architect, Giovanni Muzio. PPhotograph by Mike Peel, Parco Sempione (Milan), Wikimania 2016, MP 003, CC BY-SA 4.0

When browsing Inequalities, I did not primarily think about whether any of the proposals were workable solutions to the very broad and multifaceted problem of inequality. I thought more about whether the show succeeded in “mak[ing] the familiar strange so that it can be freshly perceived.” That is, does the show open up space for thought? Or does it — like so many other socially conscious exhibitions — merely pose familiar questions in familiar ways, evoking a heavy mood of despair and vague moral disapprobation? (Anyone who has spent a lot of time in museums over the past two decades knows what I am talking about).

Luckily, Inequalities is not a snoozefest or a lecture. Produced with input from an enormous team that includes architect Norman Foster, architectural historian Beatriz Colomina, architect and lecturer Mark Wigley, curator Hans Ulrich Obrist, and many other familiar names and institutions, including several Milanese universities and even a hospital, Inequalities succeeds in providing a platform for perspectives that feel fresh and urgent. The vastness of the show, which is impossible to take in fully in one day, is one of its strengths, as this reflects the global scope of the theme.

Interior of modular dwelling designed for displaced people on view at the Triennale. Norman Foster won two A+ Awards for this modular building system, which is called Essential Homes

The best projects here do not only seek to answer the question of how to reduce inequality or ameliorate its negative effects. They also push visitors to think about the variety of ways inequality can be measured and conceptualized: socially, economically, geographically, even biologically. (The curators describe the show as being divided, broadly, into two categories: the “geopolitics of inequality” and the “biopolitics of inequality”). In short, the very term inequality is problematized here, even as distinct inequalities are thrown into sharp — sometimes brutal — relief. Shklovsky would approve.

The section titled “Cities,” curated by Nina Bassoli, nicely introduces the key themes of the exhibition as a whole. In Bassoli’s walkthrough tour of the show, she repeatedly uses the word “contradiction” to describe how cities make inequality visible, placing wealth and poverty in close proximity to one another. As one looks closer, though, the picture becomes more complicated. One display by emphasizes the alienation of life in the upper stories of Manhattan’s new supertall towers, monuments to the wealthy residents’ distance from the people below at street level. This way of life differs markedly from the “horizontal” relationships in the city’s immigrant communities, where a lack of monetary wealth may be compensated, partly, by a wealth in familial and social relationships. More radically, this juxtaposition suggests that the drive toward capital accumulation involves the destruction of community. Each of these haughty towers takes up real estate that could be occupied by buildings that encouraged interaction.

Another section of the “Cities” exhibition showcases quiltwork “craftivism” by “Grenfell Next of Kin,” an organization of people connected to the Grenfell Tower disaster, a 2017 fire in a housing project in London that claimed 70 lives. This housing block, a fragment of working class life in the midst of the wealthy North Kensington neighborhood, became a symbol of inequality after the fire as subsequent investigations revealed that the property had been neglected for years and fitted with low cost, flammable cladding. By centering the voices of the survivors of this tragedy, the display attempts to avoid easy editorializing and present visitors directly with the deadly consequences of inequality. Another display, a map by (AB)Normal, the firm that created the exhibition design, helps to reinforce the theme of shifting paradigms. This map of the world is centered on the North Pole, not the Prime Meridian line that, for centuries, has placed Greenwich, England at the center of the Earth. If there is an overarching lesson to “Cities,” it is that the first step in equitable change is adjusting how we look at things.

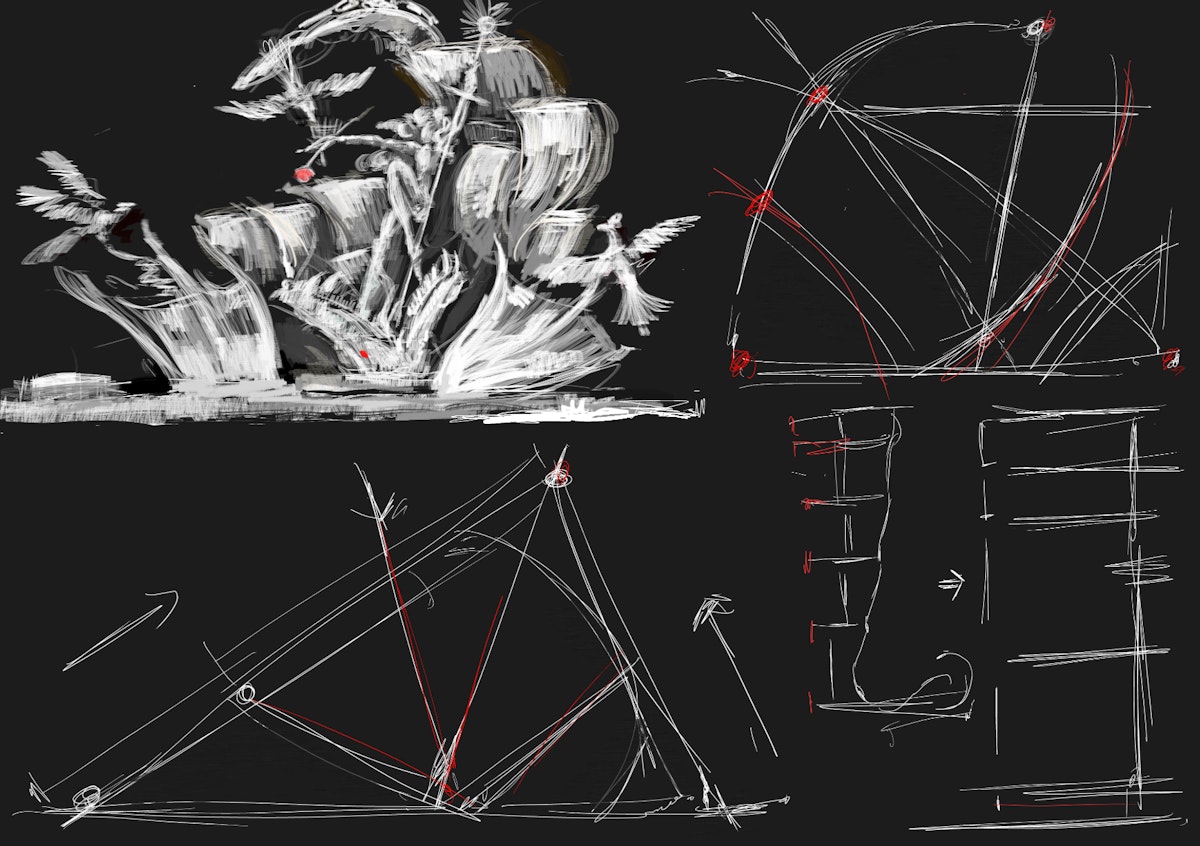

Prototype of dwelling from Norman Foster and Holcim Foundations’s Essential Homes modular system

Norman Foster’s exhibition, “Towards a More Equitable Future,” includes a display of the architect’s Essential Homes Research Project, which recently won Architizer A+Awards in two categories, Architecture+For Good and Architecture+Innovation. A collaboration between Foster and the sustainable solutions provider Holcim, this project is a prototype for housing aimed at addressing the needs of the estimated 103 million people who are currently displayed. “The objective is to design homes, not shelters, and to create communities instead of camps,” explained Foster. For just $23,500, using this prototype, workers can assemble a comfortable 580 square foot modular home from innovative lightweight materials including rollable concrete sheets. Additional projects featured in this exhibition also seek to solve the needs of displaced people. The low costs of these proposals — as well as their stylish appearance — show that it is possible for everyone in the world to live in comfort and dignity. What stands in the way is political will.

Another highlight is an installation by the social practice artist Theaster Gates titled “Clay Corpus.” Gates, an African American artist based in Chicago, has long used the techniques of storytelling and archival research to reconfigure the past, especially in ways that question prevailing racial narratives. Here, Gates transforms one of the Triennale’s prize possessions, a complete compact apartment by Ettore Sottsass called Casa Lana. With its red carpet and honey colored plywood partitions, Casa Lana always struck me as a kind of 1970s utopia, a model of urban sophistication that is also — for lack of a more technical term — cozy. Gates turns it into something else entirely, encasing the perimeter of the installation with rows of magnificent clay objects crafted by the master Japanese potter Yoshihiro Koide, a longtime resident of the village of Tokoname, which has been a center of pottery for centuries. Gates studied pottery in Tokoname and for many years has worked, in different ways, to keep the legacy of this village alive in the face of economic changes.

For his installation “Clay Corpus,” artist Theaster Gates reflects on his time spent studying pottery in Japan. This photo of the artist shows him at work in his 2012 performance piece, “Soul Manufacturing Corporation.” Locust Projects, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

“Wrapping Sottsass’s Casa Lana with Koide’s clay corpus, Gates echoes the architecture of Tokoname’s Sanpomichi path, a hill that connected the studios of potters for generations, making visible the ancestral practices of those who adorn the exterior of their homes with their wares, allowing them to weather,” explains a curatorial statement. By surveying the exterior of the apartment, visitors are able to glance into the life, work, and visual language of an artist they surely had never heard of before.

But how does this tie to Sottsass? And to the theme of inequality? These are questions that Gates leaves radically open. What we have here is simply a juxtaposition: two artists, one Eastern, one Western; one obscure, one famous; one traditional, one modern. They were brought together by a third figure: an artist who is known for situating his creative practice within communities, especially his own community in Chicago. But this work is situated within an institutional context, a museum exhibition that aims to critique global inequality.

The pieces can be put together many different ways. Perhaps Gates was interested in the uncredited Japanese influences on Sottsass’s modernism. Maybe he wanted to call attention to the way the “bachelor pad” typology of Casa Lana feels hollow when examined alongside the communal way that people live in Tokoname. Or maybe Sottsass, whose later work with Memphis is synonymous with capitalist industrial design, is being framed as an avatar of mass production, the antagonist of the endangered craft practices represented by Koide. All of these readings and more are plausible, but the installation cannot be reduced to just one of them.

It’s a cliche to say that the world is complex — but it is. Art at its best helps us begin to reckon with the complexity by disrupting the mental shortcuts we ordinarily use to make sense of the world. If you are in Milan, be sure to catch Inequalities before it closes on 9 November.

The winners of the 13th Architizer A+Awards have been announced! Looking ahead to next season? Stay up to date by subscribing to our A+Awards Newsletter.

Cover Image: Rendering of multi-unit housing project built with Norman Foster’s Essential Homes system

The post Design Won’t Save Us — But We Need It: Inside the Triennale di Milano’s Blockbuster Exhibition, “Inequalities” appeared first on Journal.