Brick, Light and Lyricism: Snøhetta Reimagines St. Louis’s Powell Hall as a Civic Beacon

A century after its debut as a vaudeville movie palace, St Louis’ iconic Powell Hall has re-entered public life with new purpose and new poise. Snøhetta’s ambitious expansion and renewal does not seek to overwrite the past — instead, the project amplifies what St. Louis already loved while opening the institution, spatially and symbolically, to new audiences of all demographics.

From the outset, Snøhetta’s co-founder Craig Dykers framed the brief less as an act of preservation and more as an act of belonging. “One of the things that was intriguing wasn’t the fact that the building was old, but that it was loved. The people of St. Louis loved it,” Dykers explained. The task, then, was to honor that affection while giving shape to a vibrant future home for the orchestra within the city’s evolving Grand Center Arts District.

“We wanted to create a sense that … this was a place for everyone to visit,” he added. This underlying ethos would shape everything about the project, from urban strategy to brick coursing.

Opening a One-Sided Palace to the City

Snøhetta‘s reimagined Powell Hall, St Louis; photo by Sam Fentress. The project was realized in collaboration with architect of record Christner Architects, theater planning consultants Schuler Shook, construction manager BSI Constructors and acoustic designers Kirkegaard.

Powell Hall’s historical typology is familiar: a singular, highly ornamented front façade and three largely blank sides, designed by legendary theater architects Rapp & Rapp and completed in 1925. This configuration was designed to serve a ticketed, pass-through movie audience, not a contemporary arts public that lingers before and after the performance. With this in mind, Snøhetta’s decisive urban move was to convert this very one-sided building into an accessible and welcoming civic actor. As Takeshi Tornier, Project Director at Snohetta, put it, “We decided that we’re going to open up this building on all sides.”

A new addition to the south introduces broad glazed arches that cut sight lines through the complex. Approach from Grand Boulevard and you can see all the way through, via a series of expansive glazed façades, to Delmar. Similarly, arrive from parking and service areas and you can see right into the enticing new entrance lobby. This visual connectivity is a distinguishing characteristic of the new addition, making wayfinding more intuitive and offering a palpable sense of permeability. Entrances, views and programmatic thresholds now cross-reference one another throughout. “We simplified all the circulation based on views, targets and simplicity,” Dykers said. In this way, the once-opaque perimeter becomes an instrument for orientation.

Huge arched windows connect the public plaza outside with the entrance lobby inside; photo by Sam Fentress.

The new plaza on Grand Boulevard is the project’s civic prelude. Snøhetta set their sweeping, sculptural extension back from the street, retaining views to Rapp & Rapp’s Greco-Roman front while making room for gathering. The principal window at the lobby operates as a public signal. “We made this giant window facing Grand and it’s like a lighthouse. It’s a beacon,” Dykers noted. Before performances, the plaza reads as an outdoor foyer. On non-performance days, it operates as a small, inviting urban square for locals living and working in the district.

Canted Brick and Lyrical Arches

The architecture of the new addition is intentionally distinct from the historic envelope of the original building, but the difference is complementary rather than combative. Inside and out, the visual language is inspired by operatic scores, defined by curves, inflections and varied, rhythmic openings. “We don’t use uniform arches. We use a kind of lyrical, bouncing arch that almost feels like a work of music,” Dykers explained, likening the forms to the movement of a conductor’s baton and the waist and F-holes of string instruments. Beyond the façade, these gestures also describe the sequences of interior balconies that let audiences “see and be seen” across a triple-height space.

Snøhetta‘s extension is constructed from stepped brickwork; photo by Sam Fentress

At the massing scale, the additions lean gently away from the site boundary, preserving key views down Grand Boulevard and striking a formal contrast to Powell Hall’s historic silhouette. The sloped exterior walls are composed of stepped surfaces made through canted brickwork that lends the building a tactile quality.

“The walls are not actually slanted, they’re stepped … Each brick course is corbeled slightly further out than the one above it,” Dykers explained. This geometry forms a subtle yet striking exterior that will express different qualities depending on the season. In summer, the inclination improves solar access to spaces below while visually lightening the mass as it rises. In winter, those brick ‘micro-ledges’ will catch snow, drawing delicate horizontal lines across the façade.

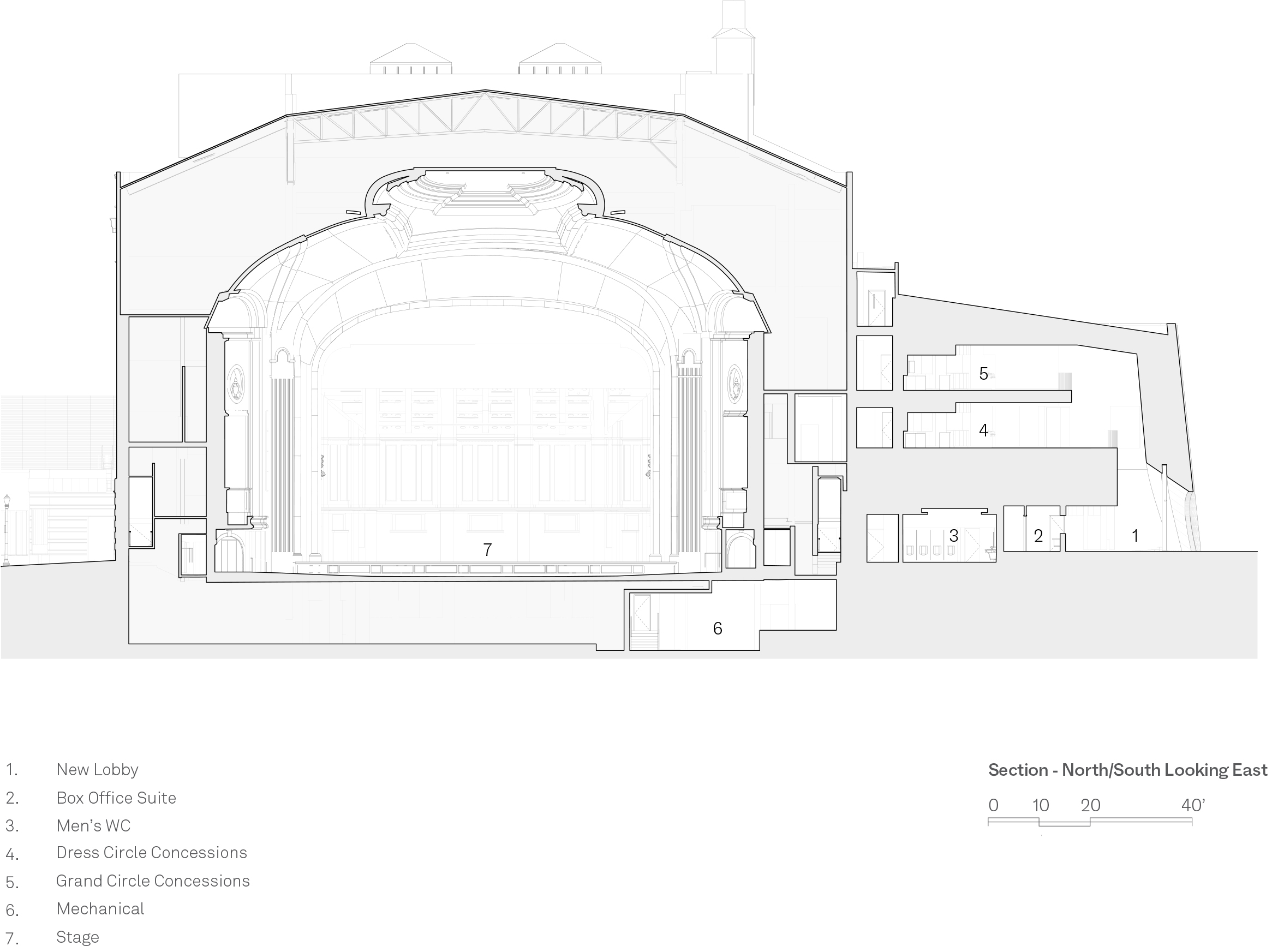

Section drawing through Powell Hall with Snøhetta’s new addition on the right; drawing courtesy of Snøhetta

Complex curves can be onerous when it comes time to build, so the designers rationalized the form of the building envelope to help with constructability. “It’s almost like you’re taking a cylinder and you’re leaning it over,” Dykers said. “So wherever you cut it horizontally, the radius doesn’t change.”

This logic allowed masons to build the façades using conventional techniques, despite the unusual geometry. “We told the mason where the center of each radius is and how it matches up for each course, and he could build it with traditional methods,” Tornier added. “It came out really nicely. I have great respect for the masons in St. Louis.”

Fabrication as Performance

If the exterior reads as a lyrical overture, the lobby’s grand stair is the solo. Rising within the triple-height entrance space, its upper parapet is constructed from a thick, formed steel ribbon. Dykers described it with characteristic awe: “The top … is solid steel that was bent and molded into this helical shape which is about as close to a Richard Serra sculpture as you’ll ever get.”

The grand staircase spirals up the triple-height lobby space; photo by Sam Fentress

Fabrication of this key architectural element unfolded like choreography. “The people would bring it to site, look at it, and then if something was off, they would mark it up, take it back to the shop, re-bend it,” Dykers recalled. “It was a piece of very iterative work.” Templates for the flared, non-repetitive treads towards the foot of the stair were crafted full-scale in plywood before being adjusted as needed on site. The resulting staircase is dramatic, joyful and profoundly tactile. The stair doubles as a physical and visual connector, a place to occupy during intermission and a sculptural register of movement that is visible to the public through the lobby’s sequence of grand arched windows.

Refurbishment You Can Hear (and Feel)

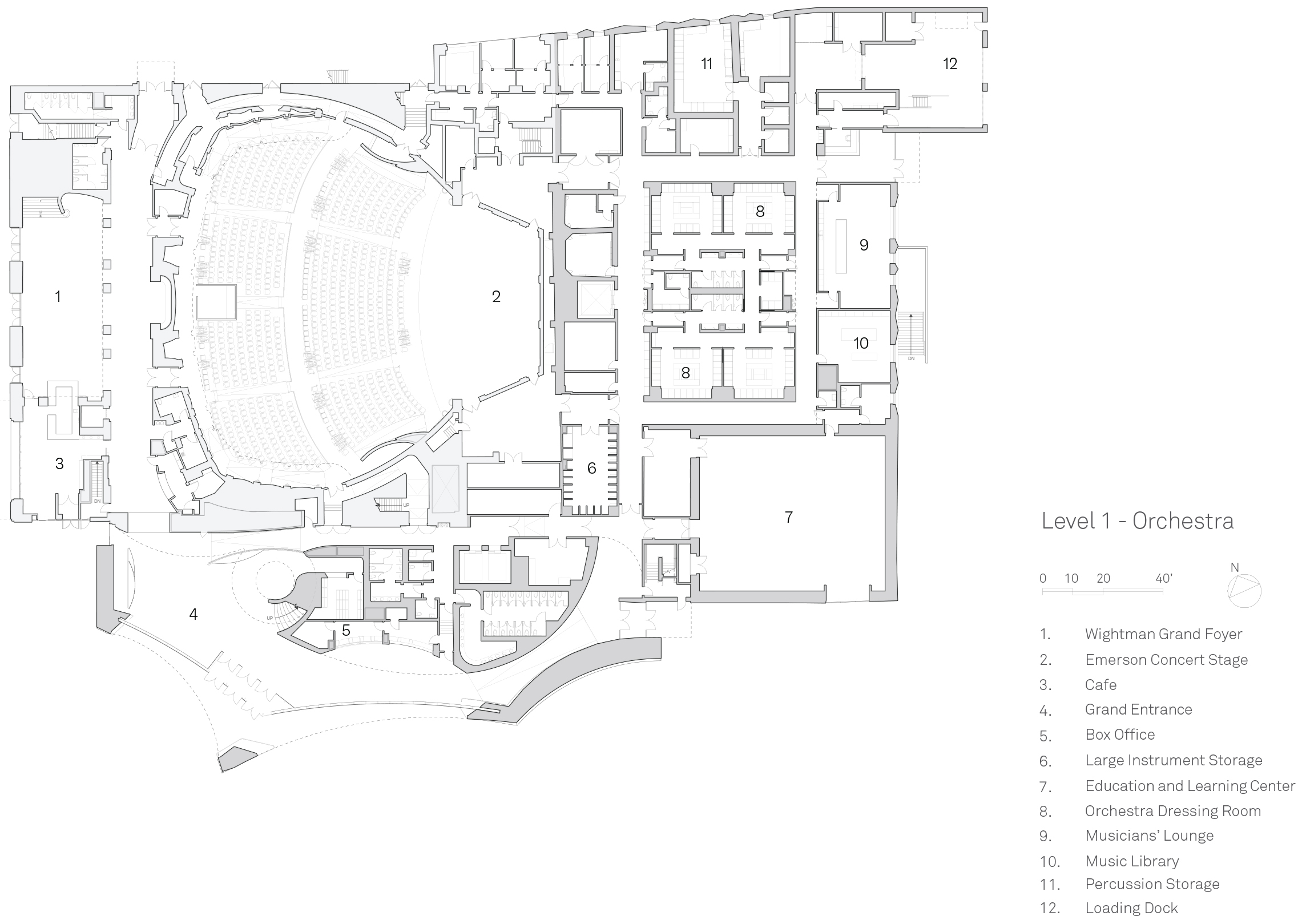

The front-of-house may be most photogenic, but the most consequential human upgrades arguably occur behind the scenes. A logical loop of circulation now threads dressing rooms, rehearsal suites, storage and stage doors, providing a simple, legible layout that maximizes comfort conditions for performers.

“We give them daylight, access to fresh air and a nice place to lounge,” Dykers explained. The lounge, scaled for the reality of 90–100 people, incorporates as much seating as possible, right down to upholstered window sills. Small, empathetic details have been integrated to truly modernize the back-of-house space: “We made a small shelf that each musician can put their little coffee cup on,” said Dykers.

Ground floor plan of Powell Hall with new lobby to the south and expanded back-of-house spaces shown to the east; drawing courtesy of Snøhetta

Beyond the visible architecture, the team undertook an exacting refurbishment of the historic hall. Air supply and acoustic tuning were carefully recalibrated without disturbing the room’s character. Despite these updates relating to less tangible characteristics, the stakes were at their highest here: “If you mess up the acoustics, that’s it. There’s no purpose in doing the project,” Dykers admitted.

The goal was to retain what musicians already considered special and refine it further for contemporary performances. Early rehearsals suggest success: “The music director said he feels he can reach out and grab the music,” Dykers noted.

The original hall was also refurbished to improve ventilation and acoustics; photo by Sam Fentress

The project also adds the Education and Learning Center, a 300-seat, wood-lined, multipurpose venue with a street-facing window. This multi-purpose space will host a diverse range of contemporary performing arts programs, as well as supporting both community partners and youth ensembles. This addition is further proof that Snøhetta’s project was not just about adding square footage: It was about providing more kinds of creative space for more kinds of people.

Heritage, Context and a Broader Public

Powell Hall sits at the confluence of complicated histories: a city shaped by rivers and industry, by cultural brilliance and economic contraction, by neighborhoods with unequal access to resources. The project recognizes this context without making it a slogan. By opening façades and entrances in every direction, the building now acknowledges the communities around it, including those who long felt unwelcome.

Perhaps most importantly, the work reframes what a concert hall should be in 2025. The historic hall remains intact, but everything around it shifts toward public life. The spaces between ticketing and ovation — plaza, lobbies, lounges, classrooms — are now active civic zones. This is adaptive reuse as cultural urbanism, calibrated for the present and the future of St Louis. In Dykers’ words, the project was about “reusing as as much as possible and adding as little as necessary.” The goal was not to create a new architectural icon — it was to foster a new relationship with musicians, with neighbors and with the city itself. On this note, Snøhetta have struck a harmonious chord, providing a valuable case study for performing arts spaces in the years ahead.

To explore more recent projects by Snøhetta, check out their growing firm profile here.

The post Brick, Light and Lyricism: Snøhetta Reimagines St. Louis’s Powell Hall as a Civic Beacon appeared first on Journal.