Intermediate Territories: Negative Space as Design Strategy in the Atacama

Call for entries: The 14th Architizer A+Awards celebrates architecture's new era of craft. Apply for publication online and in print by submitting your projects before the Main Entry Deadline on December 12th!

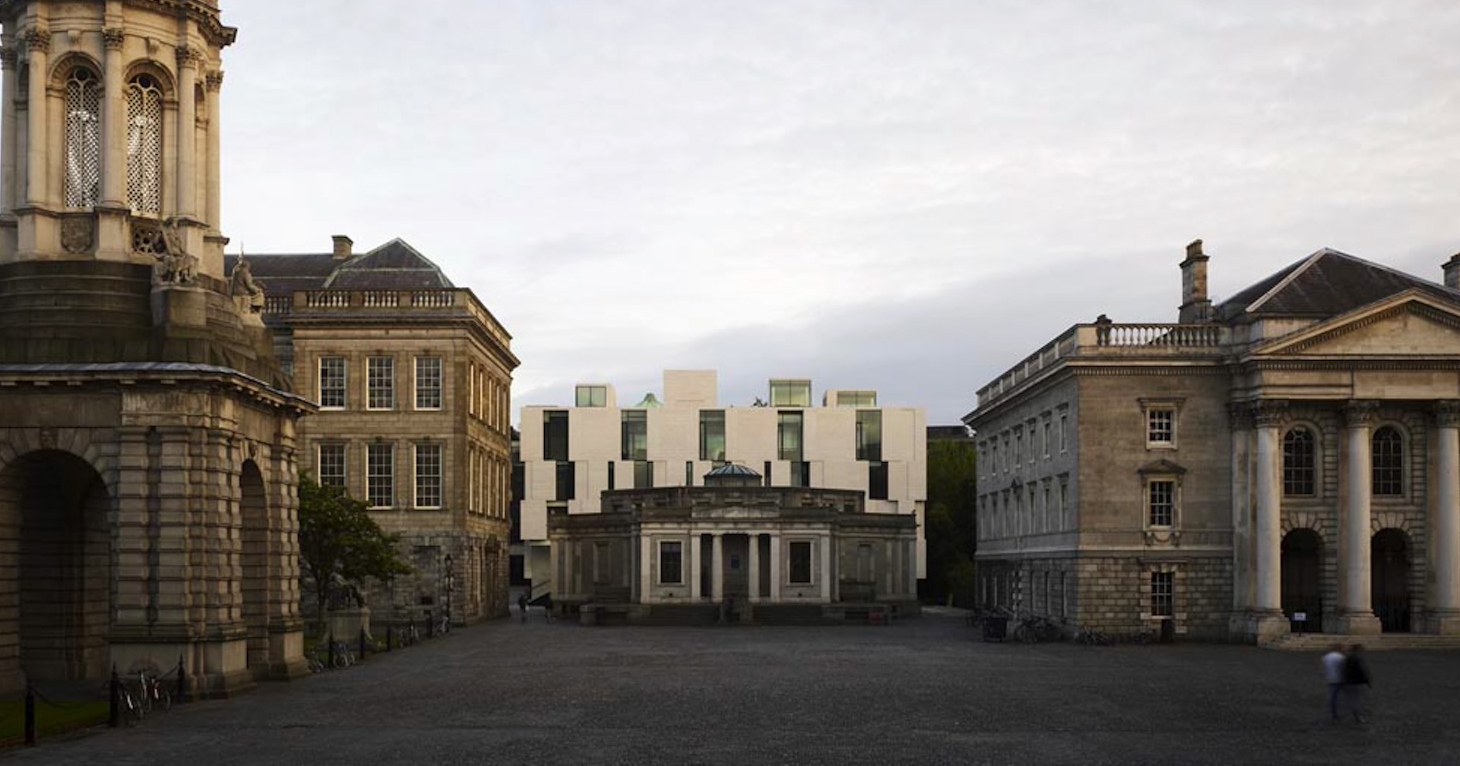

Built between 1634 and 1637, Convocation House was a westward addition — now a cornerstone — of the lower floor in the University of Oxford’s Bodleian Library. Used as a gathering point for the world-famous institution’s original governing body, the room is relatively simple, given the site’s famed antiquity, stunning fan-vaulted ceiling and ornate timber benches aside.

You could argue that this was the only place the Silence Hub could have used for a November 2019 concert comprising work from legendary contemporary composers like Arvo Part, Nils Frahm, and Philip Glass. Performed by members of the SCANJ string quartet and cellist Jacqueline Josephine, the comparatively pared-back setting was a fitting backdrop to an evening in which four of the musical pieces were silent.

Minimalism in extremis, the concept paid homage to an idea the likes of Glass have famously advocated for. Emptiness in an arrangement does not necessarily mean absence. Instead, the lack of audible noise is an essential tool that allows other elements to be heard fully. More so, we can also hear the silence.

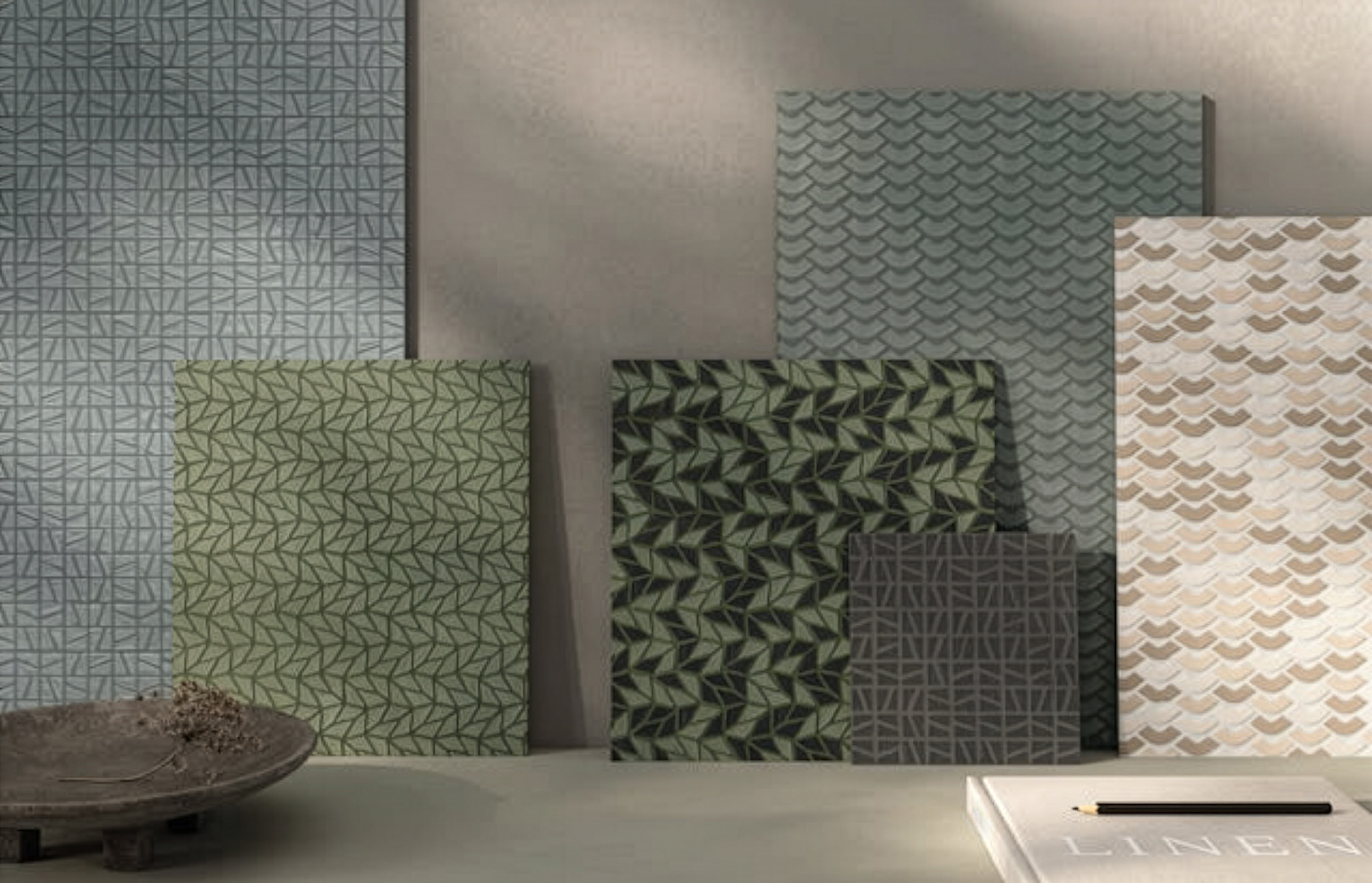

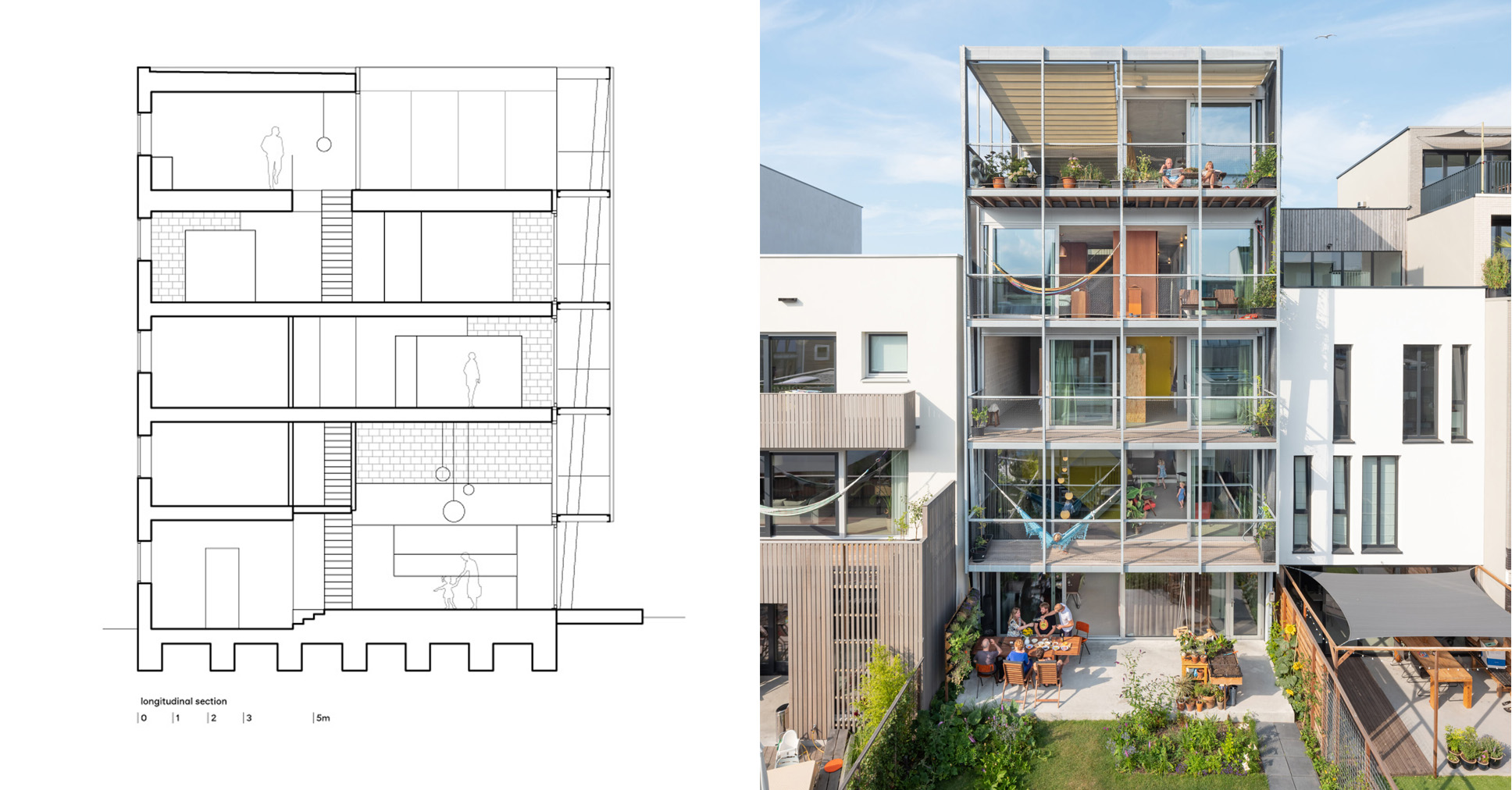

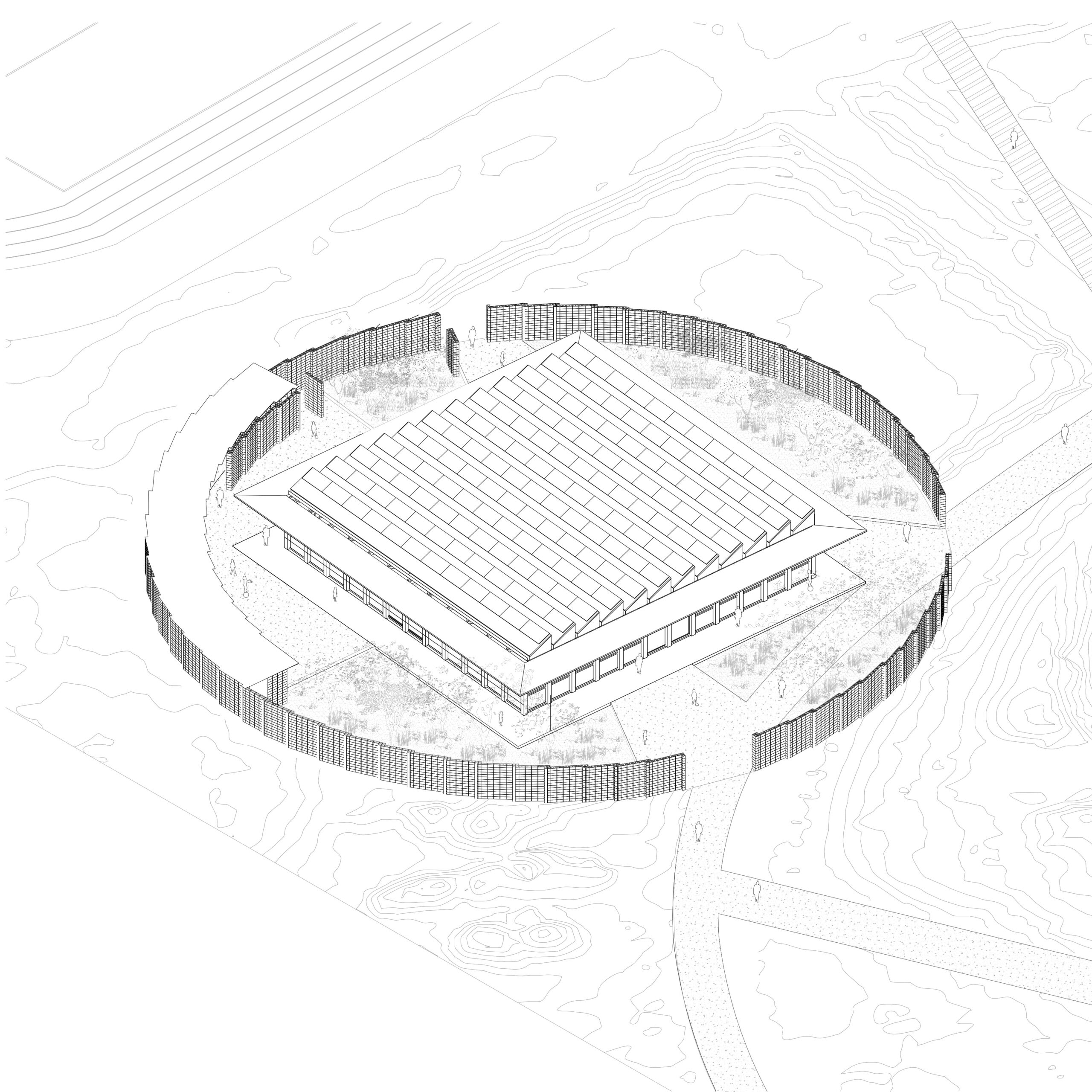

Negative space separates the boundary wall and central building at the Multipurpose Hall by Marsino Arquitectura, Chuquicamata, Chile.

Historical appraisals of this often wind up nodding to pioneering composers like Beethoven, some of classical music’s first masters of dramatic effect. But examples can be found in cultures across the globe, stretching back aeons, if you listen hard enough.

In architecture, it’s perhaps easier to trace the roots of a comparable concept — ‘ma’ (間). An aesthetic principle born in Japan, evident in both ancient and modern buildings, urban and rural spatial design, the idea is simple. Negative space is more than emptiness. The gaps between structures should be inherently beautiful and, as such, powerful.

In many ways, it is the antithesis to contemporary city planning in most corners of the globe — ironically, including super cities of the Far East. Rather than highly concentrated developments that maximize on use of available space, ma demands room so parts that are there can breathe. Not that you can’t still find individual examples of this concept at play in the densely built-up districts of Tokyo, for example.

One of the lesser acknowledged opportunities presented by ma is an open-ended use case for everything that’s not there. Many cases of the principle in practice clearly separate built elements from vacant space, but also suggest, if not insist, on what we do with that vacancy.

The transition from nature to built environment is supported by bringing the concrete pathway into the negative space of the Multipurpose Hall by Marsino Arquitectura, Chuquicamata, Chile.

A patio with stones for seating. A pebbled terrace meeting point. You get the point. This is where Multipurpose Hall in Chuquicamata, Chile, differs from the norm. Negative space is a definitive part of this masterplan by Marsino Arquitectura, but it’s up to the user what happens there.

Not just a clever name for a project, this development offers the school community in Atacama a chance to adapt, rethink, bend and subvert the area outside and inside the central building. It commits to the idea that some of the most useful architectural projects are those that have not been prescribed and will not proscribe. They are open to interpretation and truly celebrate the joy of a blank canvas.

In many ways, this is the direct result of circumstance and location. Situated on the outskirts of Calama, a city known as the gateway to the Atacama Desert, Marsino Arquitectura describes the controlled exterior as “intermediate space” — necessary for successful transition from uncharted and untamed badlands beyond, into the single-story building interior.

The Multipurpose Hall by Marsino Arquitectura in Chuquicamata, Chile offers open-ended use cases.

It’s there to make the switch from wild arid landscape to sanitized human-made environment less jarring, an approach supported by the elliptical floor plan, inviting an external concrete sidewalk into the school grounds. And it’s possible this may have failed in achieving the sense of tranquil transformation had that negative space been created with a clearer, fixed use in mind.

Composers such as Part and Glass have often been criticized for creating work which is essentially simplicity disguised as genius, lacking the complexity required to qualify as the ranks of musical giant. But this misses the details of their arrangements, how emptiness and silence are used for the end result. When we focus on this, their talent reveals itself.

The same is true at Chuquicamata — one glance suggests a basic design born from limited consideration. Then we try and picture what this would have been like had the opposite been prioritized: a busy, regimented exterior, or a single step from surrounding nature into the building. And vice versa. Both approaches could have been tempting. Neither of which would have stood a chance of catalyzing this essay.

Call for entries: The 14th Architizer A+Awards celebrates architecture's new era of craft. Apply for publication online and in print by submitting your projects before the Main Entry Deadline on December 12th!

The post Intermediate Territories: Negative Space as Design Strategy in the Atacama appeared first on Journal.