The Death of 20th Century Idealism: Are Today’s Architects Too Pragmatic?

Got a project that’s too wild for this world? Submit your conceptual works, images and ideas for global recognition and print publication in the 2025 Vision Awards, June 6th marks the end of the Main Entry period — click here to submit your work.

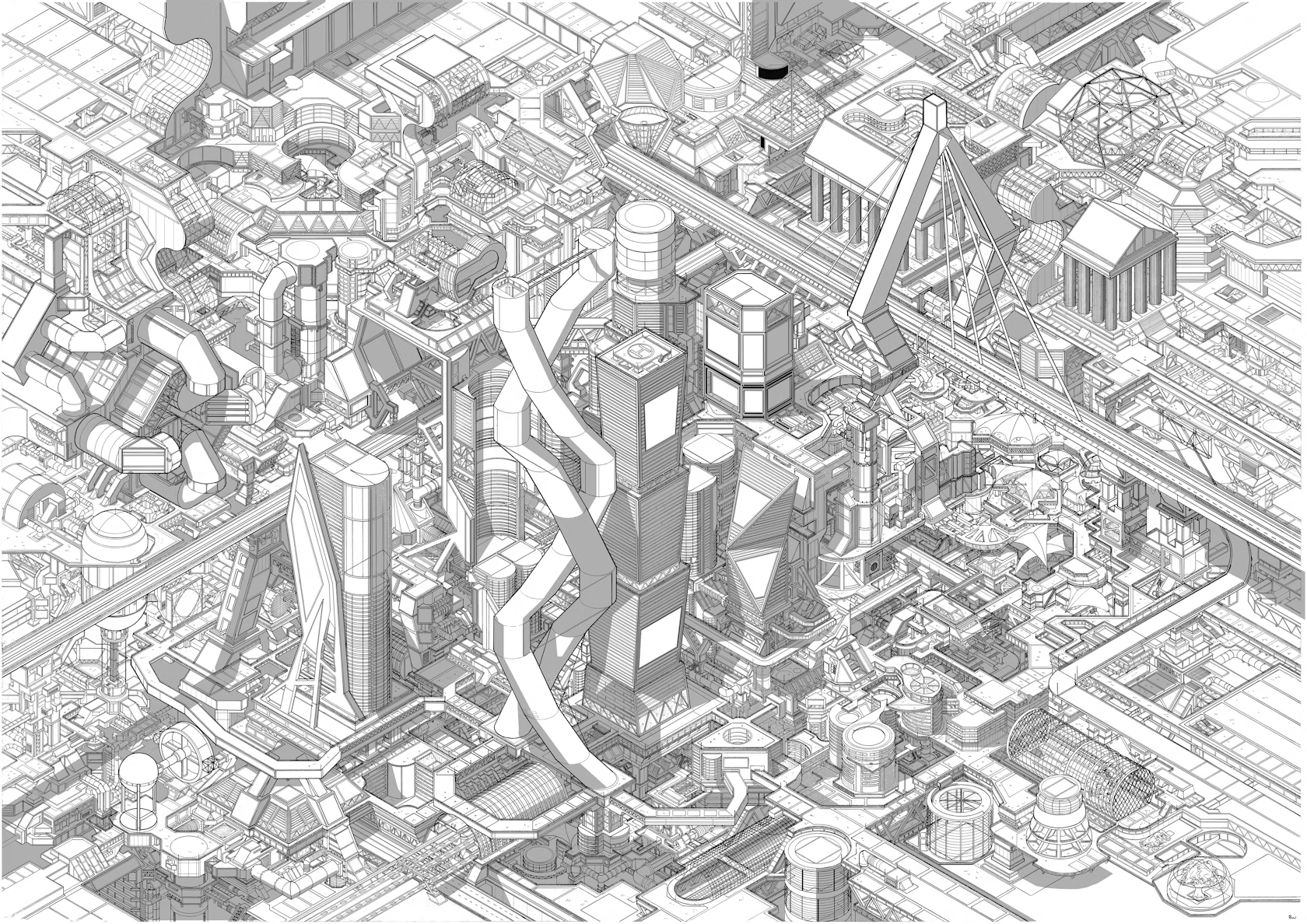

The word “ideal” carries a subtle yet powerful trap, particularly in the context of city-making. Detached from the practicalities of construction, many architects throughout history have assumed a godlike role, crafting visionary urban proposals prioritizing perfection over feasibility. These so-called architectural utopias were often driven by the desire to radically improve how societies function, adopting the belief that reshaping physical environments could lead to social transformation. Yet, the allure of the ideal can be double-edged, often leading to designs that, albeit “perfect,” have repeatedly resulted in unintended consequences such as social exclusion, control, and isolation rather than the promised harmony.

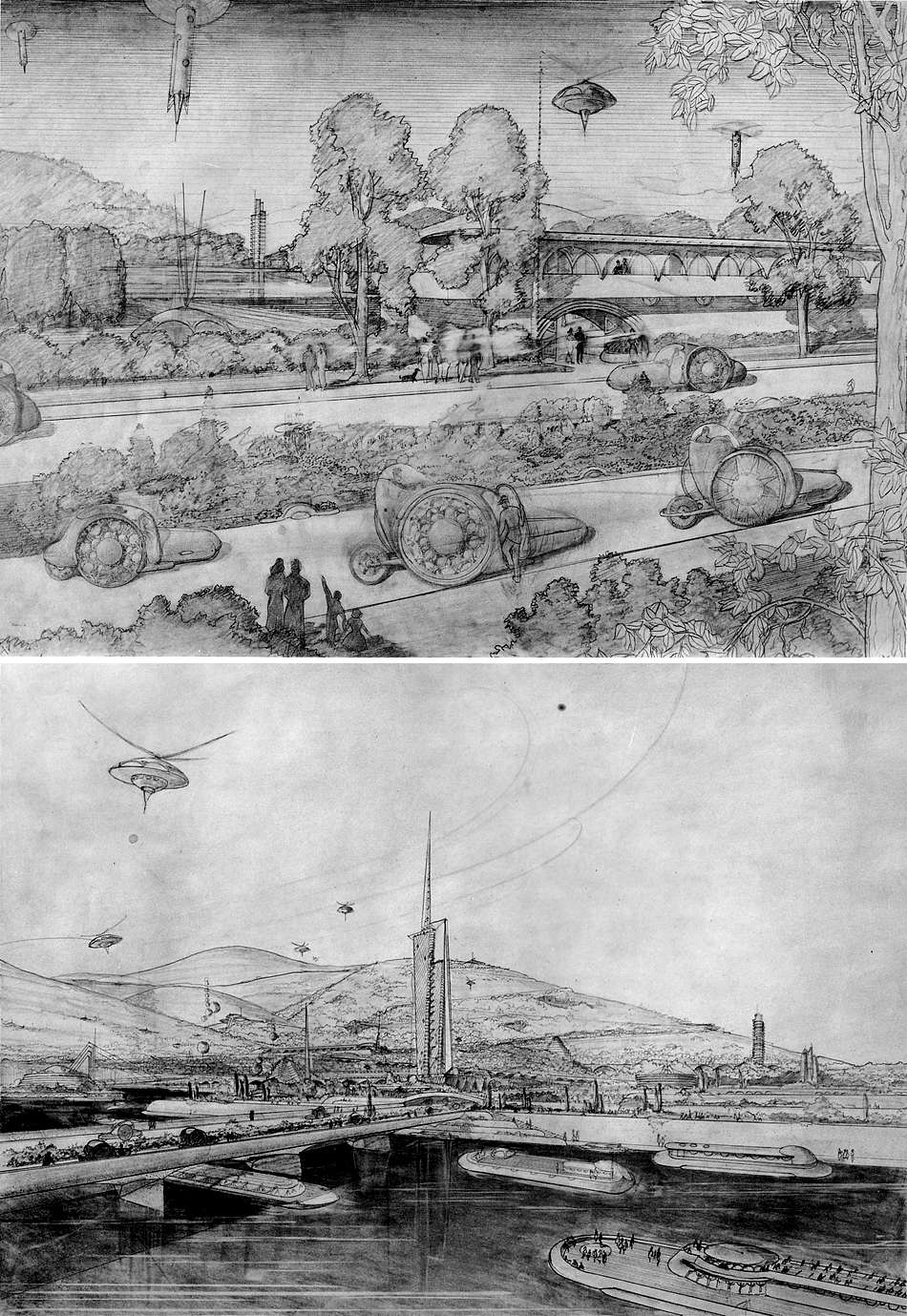

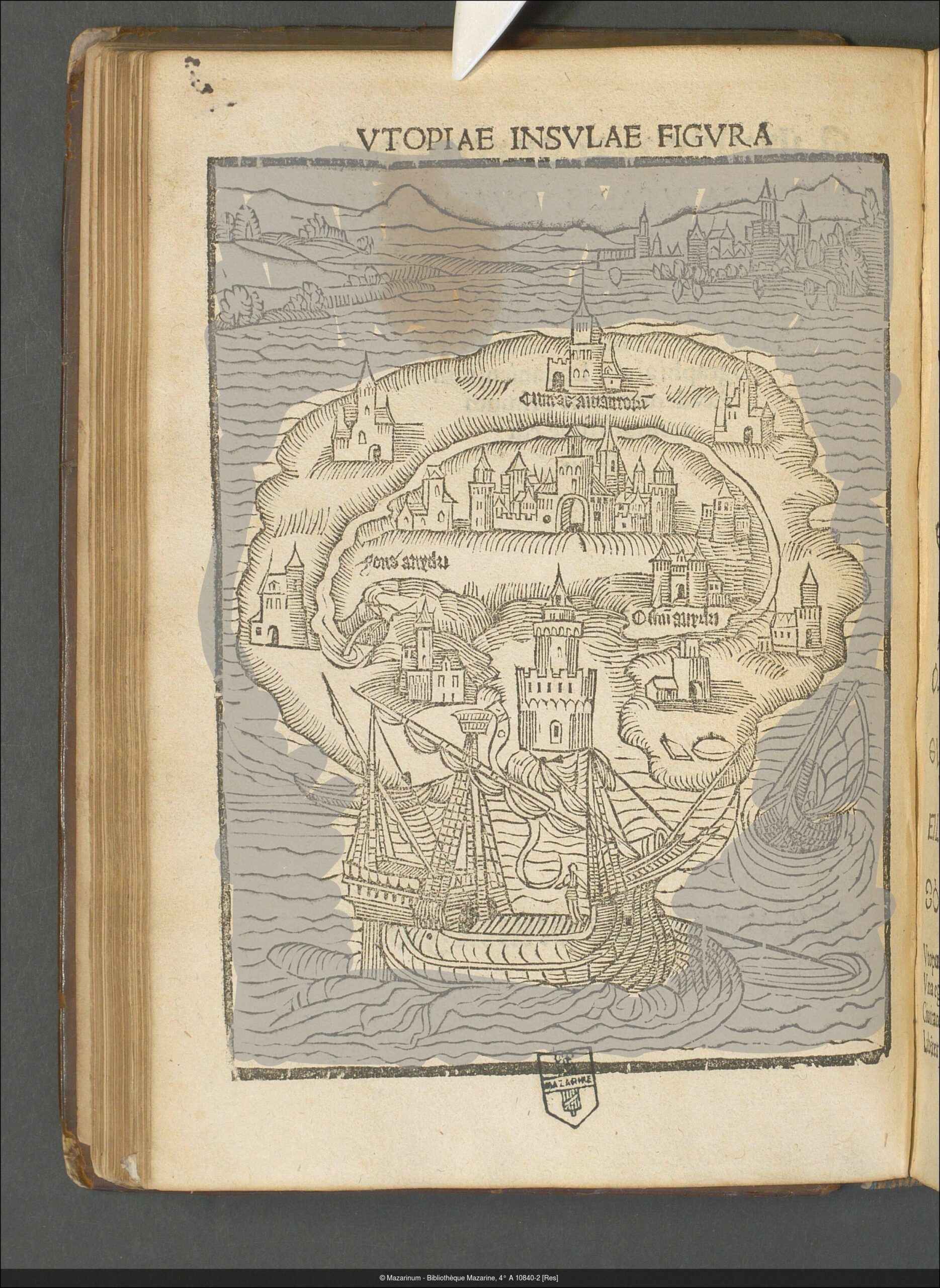

During the 20th century, a big surge of visionary utopias emerged through the practice of architecture. Of course, there were many earlier “iterations” of utopian visions, from drawings of Amaurot (Thomas More’s utopian capital) to the Cenotaph for Sir Isaac Newton by Étienne-Louis Boullée; still, the 20th century marked an astounding era of futuristic designs and technological aspirations. Perhaps the desire to explore more radical built environments and apply the modernism style to an urban scale was the driving force behind this endeavor. And yet, now nearly at the end of the first quarter of the 21st century, architectural utopianism has declined. Have architects abandoned grand ideals in favor of more practical, incremental approaches? Have they stopped dreaming big, or have these utopian models simply failed to live up to their promises?

To explore the following questions, let’s first delve into some of the most famous, radical, and—according to some—failed architectural utopian projects.

Brasilia

Anonymous Unknown author, Brasilia aerea torredetv1304 4713, CC BY 3.0

Brasilia was designed by urbanist Lucio Costa and is filled with some of the most beautiful, sculptural and symbolic buildings by Oscar Niemeyer. Costa’s ambition was to create a progressive city that would offer a good quality of life to its residents. Following principles of orderly, rational, and systematic design, the city was conceived in four scales: the Monumental, meaning the long axes; the Gregarious, meaning the civic architecture; the Quotidian, for the residential areas; and the Bucolic, for the open space.

In theory, the proposal signified an era of profound transformation. However, numerous problems arose when construction began: work camps (in the form of slumps) cropped around the city, and a massive segregation between upper and lower class occurred. Additionally, the design failed to account for pedestrian accessibility (relying heavily on cars) or consider the effects of land and urban economics. Albeit beautiful and impressive, transportation issues, urban sprawl and inequality are very real challenges modern-day Brasilia has to address, hence the label of “a cautionary tale for urban dreamers.”

Radiant City

Chandigarh, The theatre sector 17 by Richard Weil , via Flickr

Perhaps the most radical suggestion for the “implementation” of Radiant City was Le Corbusier’s idea to demolish historic parts of Paris. He envisioned a city organized in perfect symmetry, influenced by the parts of the human body and how they operate together efficiently. Famously, he viewed the city as a living organism — a machine for effective inhabitation. Vertical concrete towers arranged in a symmetrical grid, combined with large open spaces fit for public transportation, would offer social housing and accessibility.

A business district would connect to the residential and commercial zones at the center via underground passages. Even though Radiant City was never implemented, it inspired the urban plan for Chandigarh in India, drawn by Le Corbusier in the 1950s. Still, despite its ambitious design, the city (according to some critics) “lacked Indianness.” At the same time, it very quickly outgrew its capacity, with the prominent green strip that surrounded it becoming occupied by scruffy homes and shops.

Broadacre City

Broadacre City was essentially Frank Lloyd Wright’s vision of an architectural and urban democratic city. Placing the individual at the center of design, the proposal ensured each inhabitant a home, a farm and a place of employment. In parallel, utilities of everyday necessity such as power, transportation, and mediums of exchange were publicly owned.

Although the city was much more chaotic than the previous two examples, it was based on a genuinely democratic society where the government was strictly impersonal. Following such a free-thinking and complex design, Broadacre City was never realized. However, it fueled many of Wright’s architectural community projects and provided a framework for American city planning processes.

Ideal Cities, Flawed Realities

Bibliothèque Mazarine, Thomas More Utopia 1516 VTOPIAE INSVLAE FIGVRA (Bibliothèque Mazarine) Skull Version, CC BY-SA 4.0

Today, the spirit of architectural utopianism seems to linger more as a cautionary tale than a guiding light. In an era increasingly defined by economic constraints, climate urgency, and social complexity, the focus has shifted toward feasibility, resilience, and incremental change. The profession often celebrates what can be built rather than what dares to imagine, leaving many visionary, unbuilt projects overlooked or dismissed as impractical.

Consequently, holistic and speculative thinking has taken a backseat to metrics, deliverables, and regulatory compliance. While this pragmatism addresses real-world constraints, it raises a pressing question: have we lost something vital by retreating from the imaginative realm? The challenge for today’s architects is not simply to dream or to build, but to reclaim the space in between, where visionary thinking can coexist with grounded execution.

Got a project that’s too wild for this world? Submit your conceptual works, images and ideas for global recognition and print publication in the 2025 Vision Awards, June 6th marks the end of the Main Entry period — click here to submit your work.

Featured image: Utopia by Peter Wheatcroft / 10 Design, 2023 Vision Awards, Special Mention

The post The Death of 20th Century Idealism: Are Today’s Architects Too Pragmatic? appeared first on Journal.