Precision Fatigue: Escaping the Sterility of Digital Perfection in Design

Ismail Seleit is a speaker at RELEASE [AEC] — the first tech event designed to help professionals stay on the cutting edge of innovation and master the tools of the future. As technology, digital solutions and artificial intelligence continue to reshape the AEC sector, a unique event like RELEASE [AEC] is more essential than ever. The inaugural edition will be held in Paris on November 17, 2025. The event is 100% free for AEC practitioners: register today!

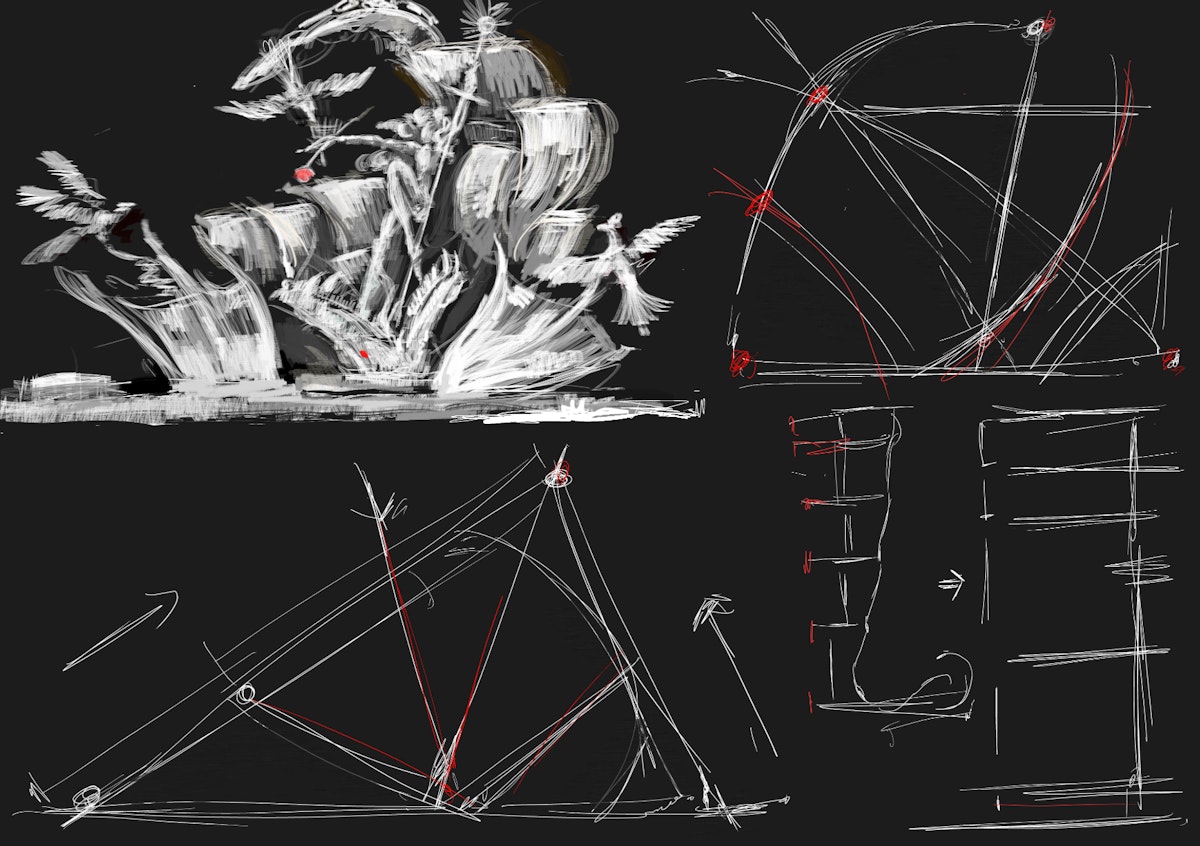

For years, my relationship with the computer was about control. I was obsessed with knowing the perfect sequence of commands to translate a thought in my head into a digital reality. But my head doesn’t work that way; it’s messy. Thoughts collide and visions are in constant flux. By the time I could force an idea through the rigid logic of software, the idea itself felt obsolete. This process demanded precision far too early, funneling all possibilities into a narrow channel and limiting the playfulness of design. We started to think like the machines we were using, where everything became an array of copy-pasted elements, and even complex designs were just modulations on a simple, predictable surface.

This new way of working with AI is the complete opposite. Naturally, my first instinct was to handle it as I always had: to try and force it to generate precise, “buildable” things. It refused. That refusal was annoying at first, but then I began to understand. There are more critical things than precision, especially in the beginning.

It’s like writing this article. I have a destination in mind, but I am not counting the words or agonizing over sentence structure on the first pass. I have to focus on what matters first.

From Designer to Precision-Policer — And Back Again

Over the years, the pendulum in architecture has swung too far toward technicality. You can’t even start drawing if two lines are microscopically off-parallel or a dimension doesn’t read “500.000000 mm.” Our role shifted from designer to precision-policer, and we praised this as the highest virtue. I’m not saying perfectionism is bad, but our tools have skewed our priorities to the point that nothing on a resume seems to matter more than the “software skills” section. It feels like we are designing for computers, not for the physical world — a world which, by the way, is messy and has nothing to do with perfectly straight lines that snap at 90 degrees.

Over the years, the pendulum in architecture has swung too far toward technicality. You can’t even start drawing if two lines are microscopically off-parallel or a dimension doesn’t read “500.000000 mm.” Our role shifted from designer to precision-policer, and we praised this as the highest virtue. I’m not saying perfectionism is bad, but our tools have skewed our priorities to the point that nothing on a resume seems to matter more than the “software skills” section. It feels like we are designing for computers, not for the physical world — a world which, by the way, is messy and has nothing to do with perfectly straight lines that snap at 90 degrees.

As the architect Hassan Fathy called it, we were practicing “T-square architecture,” void of aesthetic or expressive quality. Now, it has become even more obsessively lured into the sterile world of digital precision.

This was different. Suddenly, I could communicate an idea. I could describe the feeling of a building in a particular context, and the computer would respond. There was no need to memorize a sequence of commands to produce an empty shell and then wonder if it ever matched the thing in my head. I could write down my thoughts, and the machine would not only help me visualize them but also suggest things I hadn’t asked for: things that I hadn’t commanded.

It was a humbling experience. I could spend an afternoon in a conversation with the computer, a conversation held not just in text, but through images. And the dialogue wasn’t about the mathematical formula for a perfect hyperbolic form; it was about feeling, light, materiality, composition and philosophy.

This is where the challenge — and the point — lies. Trying to tame these generative models to serve me like the old software was missing the lesson. I had to let go. If I knew exactly what I wanted, I would just model it the old way. But the truth is, what I want is never that clear, and our current tools fail us in that ambiguous, fertile space.

Natural Selection: Returning to the Story and the Idea

The process is inherently messy, and that’s what makes it feel right. It embraces unpredictability, intuition and the beautiful accidents that happen when ideas get lost in translation. It feels more grounded in the reality of how we ought to design for the physical world. This is where we can draw a powerful analogy from nature. Evolution doesn’t work from a perfect blueprint; it thrives on messiness. It uses random mutations — mistakes, essentially — to explore possibilities. Most of these variations fail, but some lead to brilliant, unexpected adaptations. The sterile perfection of “T-square architecture” is like trying to design a forest by copy-pasting one perfect, computer-generated tree. A real forest is a chaotic, resilient, and beautiful system born from imperfection.

The process is inherently messy, and that’s what makes it feel right. It embraces unpredictability, intuition and the beautiful accidents that happen when ideas get lost in translation. It feels more grounded in the reality of how we ought to design for the physical world. This is where we can draw a powerful analogy from nature. Evolution doesn’t work from a perfect blueprint; it thrives on messiness. It uses random mutations — mistakes, essentially — to explore possibilities. Most of these variations fail, but some lead to brilliant, unexpected adaptations. The sterile perfection of “T-square architecture” is like trying to design a forest by copy-pasting one perfect, computer-generated tree. A real forest is a chaotic, resilient, and beautiful system born from imperfection.

Working with generative AI feels like stepping into the role of natural selection. You guide the process, apply pressure and curate the outcomes, but you don’t dictate every step. You let go of the need for absolute control and allow for emergent complexity.

Suddenly, the emphasis returns to the story and the idea. This is what makes you shine in a sea of accessible, shiny images. You can now easily spot a generic image lazily generated from someone else’s prompt, the same way you can spot a ChatGPT-written email. The process remains genuine because the story still counts, and we instinctively value human-created narratives. This doesn’t mean you can’t use the tools to co-create. You are reading this article after it has passed through an LLM, not only for punctuation and editing but also because the ideas themselves were solidified in a conversation I had with it.

The Importance of Low-Rank Adaptations (LoRAs)

Screenshot

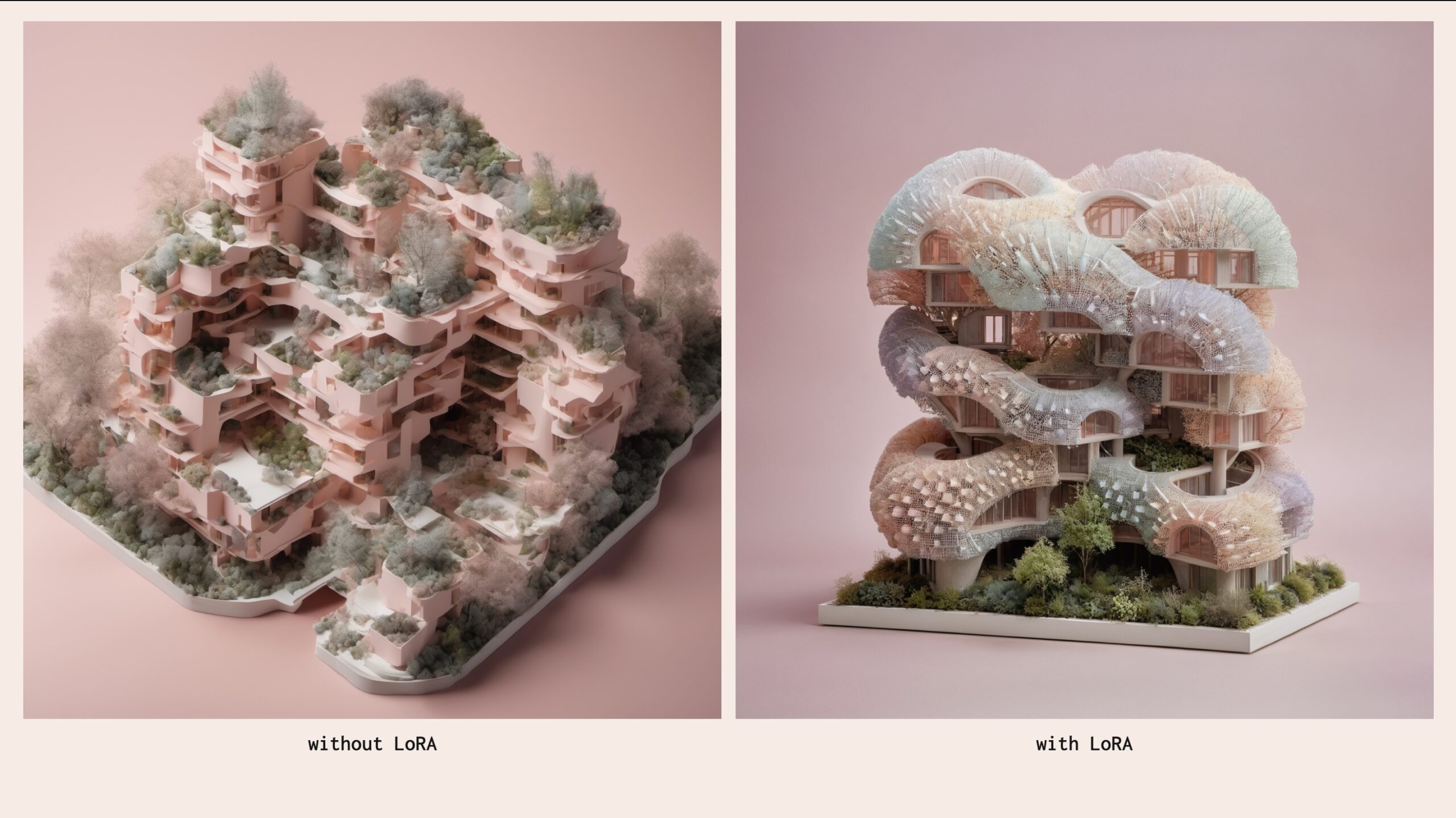

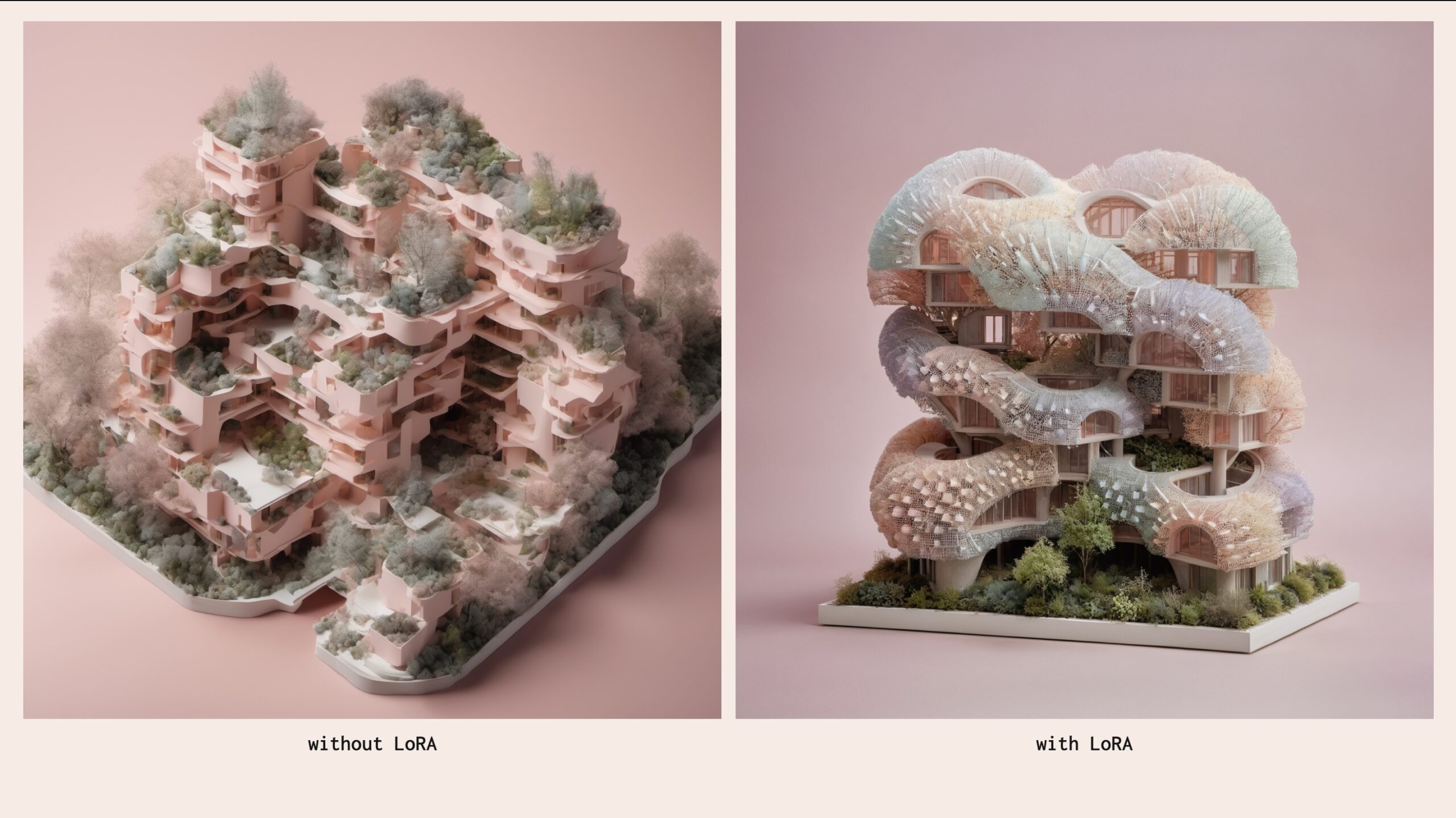

All of this has made me realize how much meaning an image holds beyond its geometry and textures. It’s the subtleties that evoke a feeling in the first second you see it. This is why teaching the model is crucial. A base model has seen everything, so it will naturally resort to the most generic, “average” scenario. In a highly specialized and image-obsessed field like architecture, that’s the last thing you want.

This is where LoRAs, or Low-Rank Adaptations, come in. In essence, they are tiny, specialized models that you train and attach to the main model, like plugins. They add a specific bias, transforming a generic AI that knows billions of images into a specialist that deeply understands a specific concept, your concept. They are easy to train, versatile, and can be mixed together. If trained well, they are powerful enough to completely change how you work. If you can conquer the image space in architecture, you’ve cracked 40-50% of the workflow, especially in the early phases.

This is a breath of fresh air for the industry. Because it is so novel and disruptive, it will take time to see a full shift. But it made me realize how much we needed it.

Sometimes, you have to let go to get precisely what you want.

Ismail Seleit is a speaker at RELEASE [AEC] — the first tech event designed to help professionals stay on the cutting edge of innovation and master the tools of the future. As technology, digital solutions and artificial intelligence continue to reshape the AEC sector, a unique event like RELEASE [AEC] is more essential than ever. The inaugural edition will be held in Paris on November 17, 2025. The event is 100% free for AEC practitioners: register today!

The post Precision Fatigue: Escaping the Sterility of Digital Perfection in Design appeared first on Journal.