Analog Architecture: Why Designers Are Putting Physical Models Back in the Spotlight

The votes for the 2025 Vision Awards have been counted! Discover this year's cohort of top architectural representations and sign up for the program newsletter for future updates.

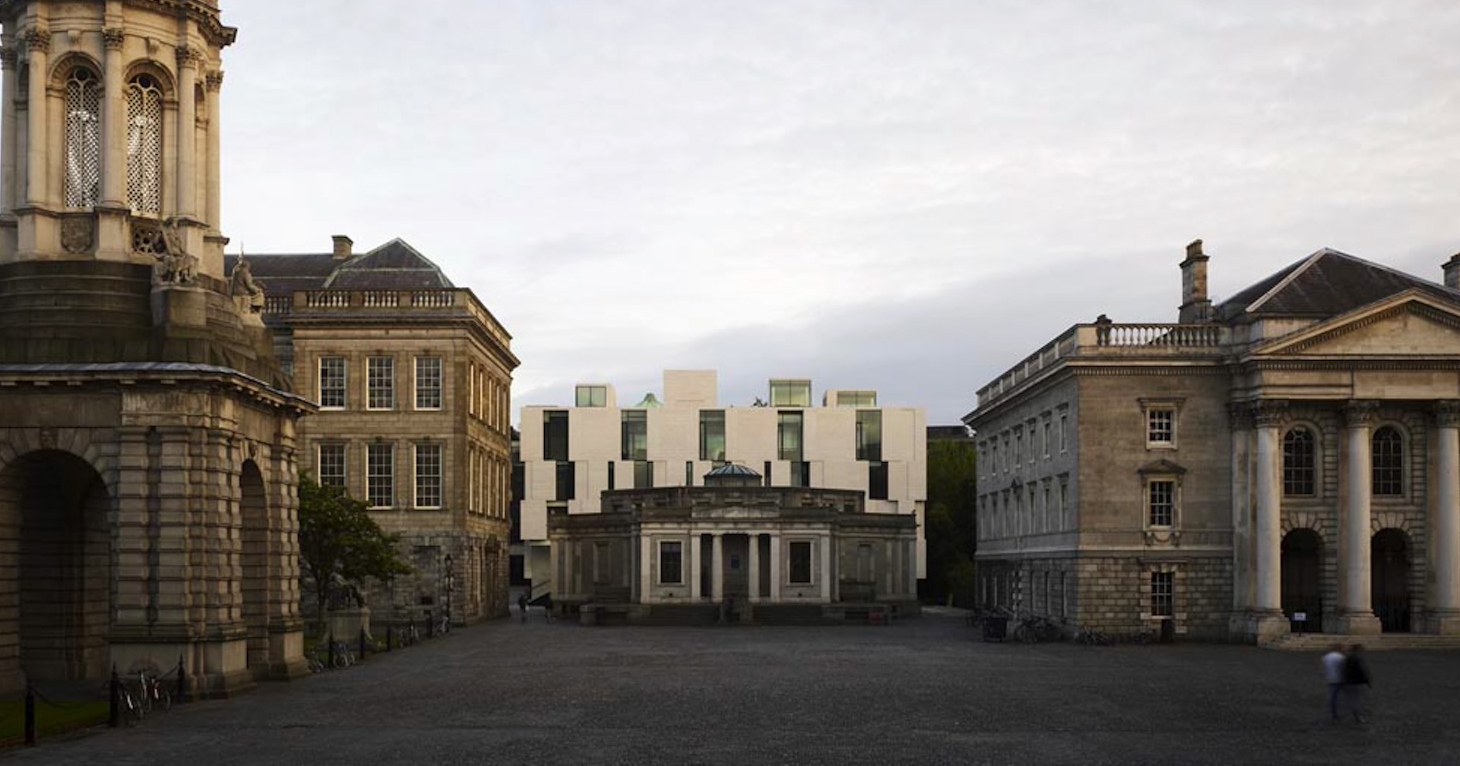

For years, both architectural education and practice have been moving steadily toward the digital realm. Sometime in the late 2010s, most of us slowly accepted that the future of the discipline would be screen-based: software kept getting faster, AI was just around the corner and model-making already felt like something we should leave in the past. After all, why should we struggle with blades and glue when 3D models could solve everything?

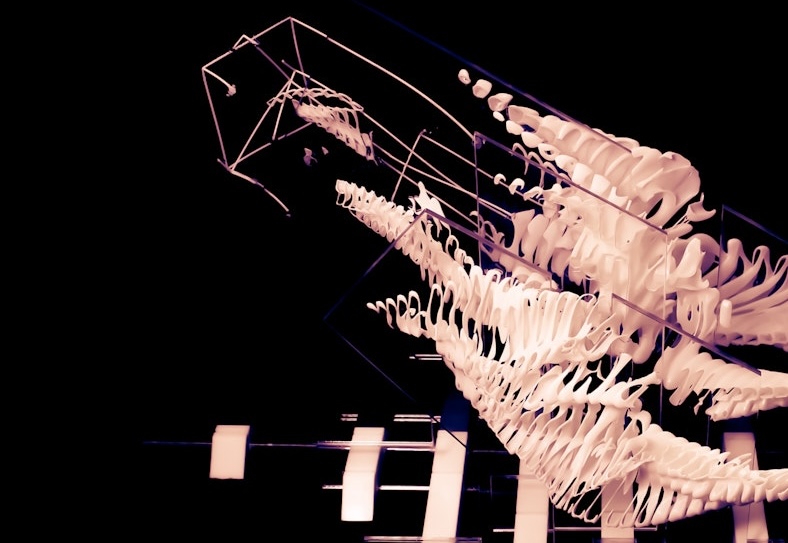

Yet, the more digital our tools became, the more one thing was missing in our work: presence — whether that be material, spatial or conceptual. (All these screens everywhere, but nothing to touch an architect’s soul like a plain old model).

But somewhere between the endless iterations and frictionless visualization, it became clear that architecture will always need a medium that slows us down and forces ideas into real space. And this year’s Vision Awards winners most certainly affirm that point. Analog models are definitely returning to the spotlight, not as nostalgic artifacts, but as a serious tool for design thinking.

From Screen Fatigue to Spatial Clarity: The Case for Tactility

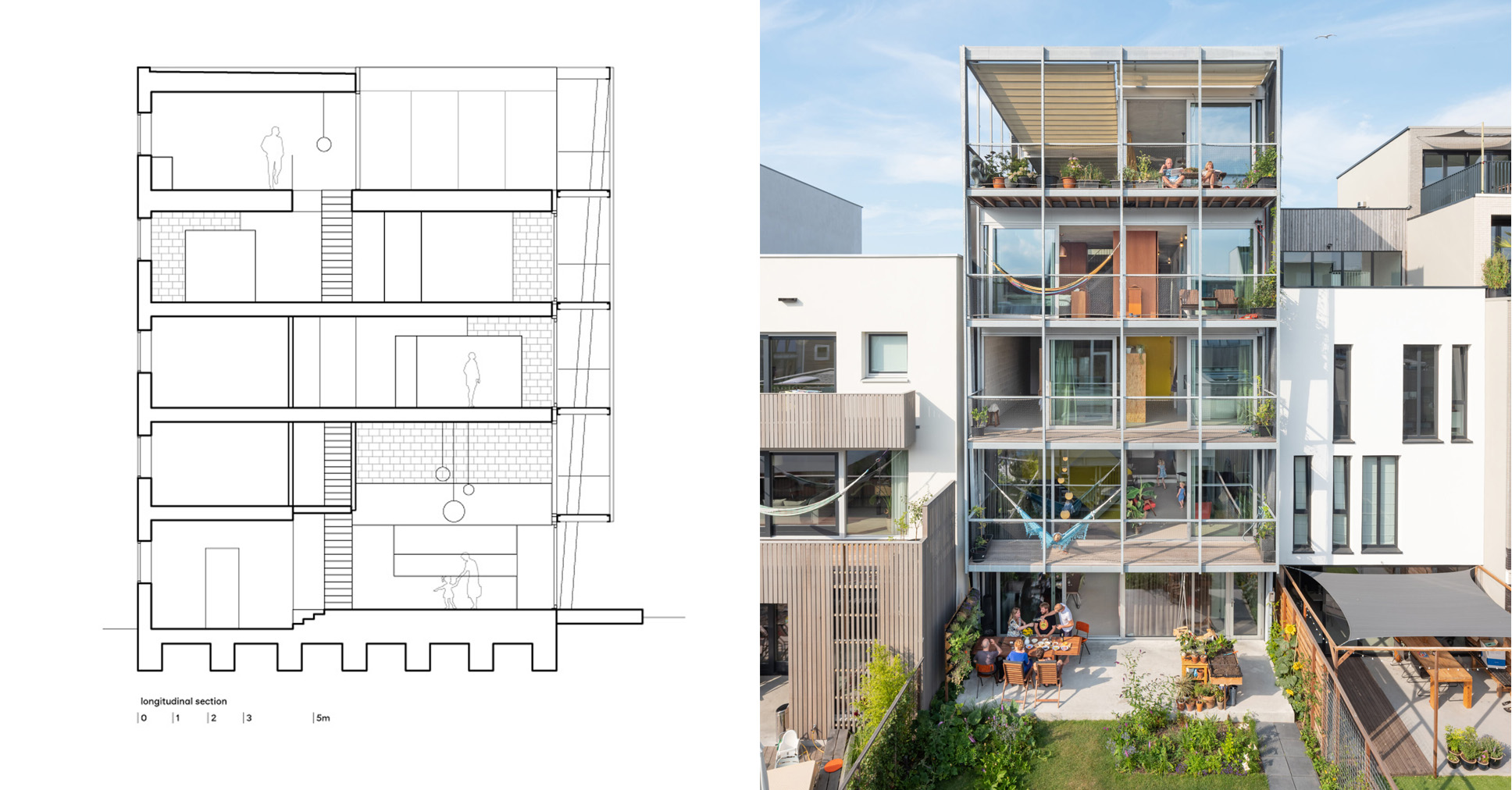

The House for Twos: Living and Collecting within Cones and Funnels by Alexander Htet Kyaw, 2025 Vision Awards, Presentation Model, Editor’s Choice Winner

One reason physical models feel newly relevant is the sheer volume of time architects now spend on screens. Most of the discipline’s workflow has shifted into software environments, and with that shift came a level of visual output that earlier generations never had to manage. AI accelerates this even further by producing endless variations at the click of a button. At some point, the ease of generating ideas begins to erode the ability to evaluate them.

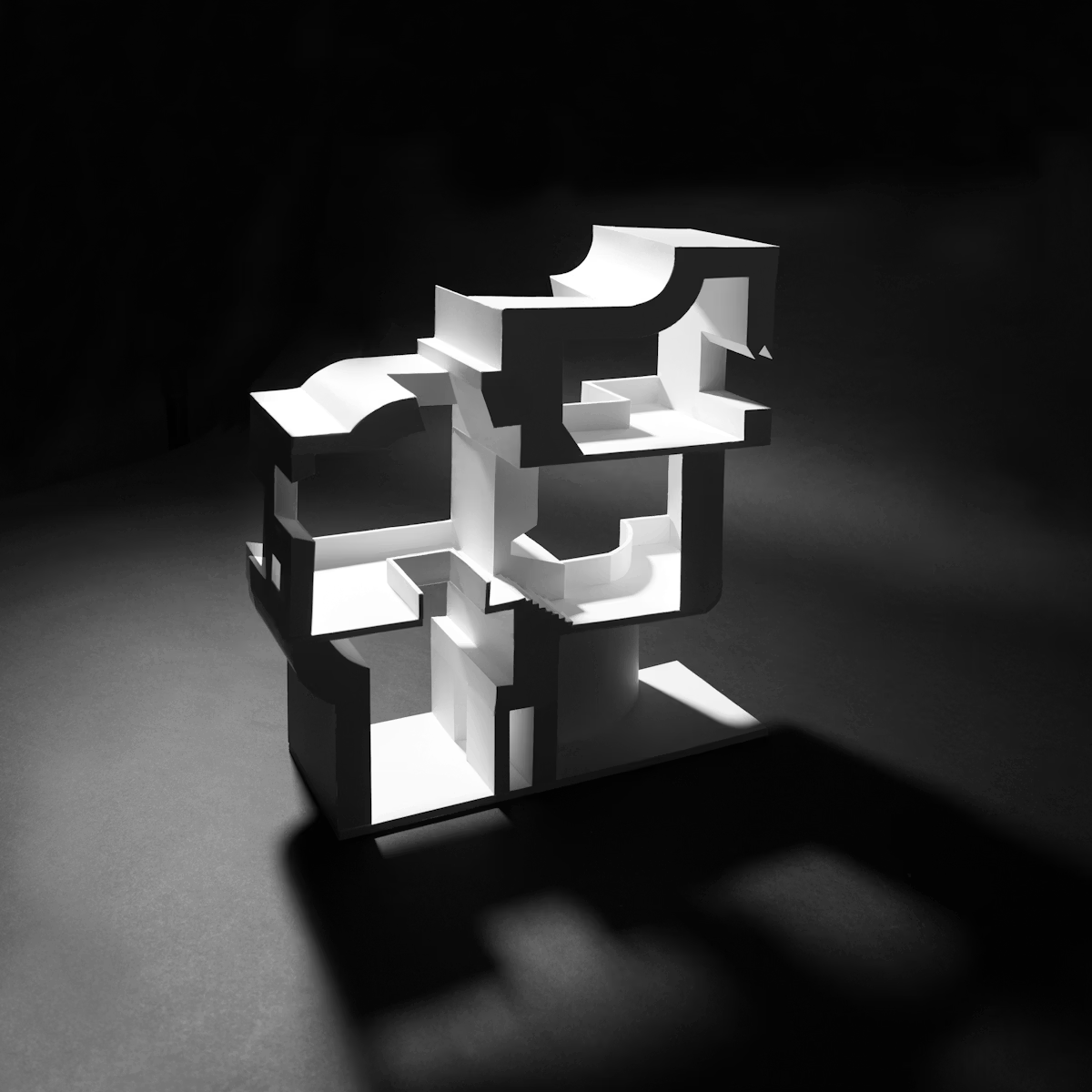

In contrast, tactility offers a corrective. A physical model introduces a level of resistance that digital tools cannot simulate. Cutting, assembling or testing materials requires commitment rather than casual iteration. The process slows just enough for decisions to become intentional, not automated, and that slowing restores a sense of focus often lost in fast-paced digital workflows.

Poché, Revisited by Fergal Tse, Editor’s Choice Winner, Concept Model, 2025 Vision Awards

Tactile engagement also reintroduces the body into the act of designing. Holding, shifting and adjusting a physical object offers a kind of understanding that does not translate through a mouse or a trackpad. The simple act of making grounds the work in reality, reminding architects that design is not only visual but tactile.

In our now digital culture that is defined by speed and abundance, tactility stands out because it simply brings clarity. The designer gets to step out of the cycle of constant on-screen refinement and re-enter the physical conditions that architecture ultimately inhabits.

Physical Models Clarify Architecture’s Spatial Logic

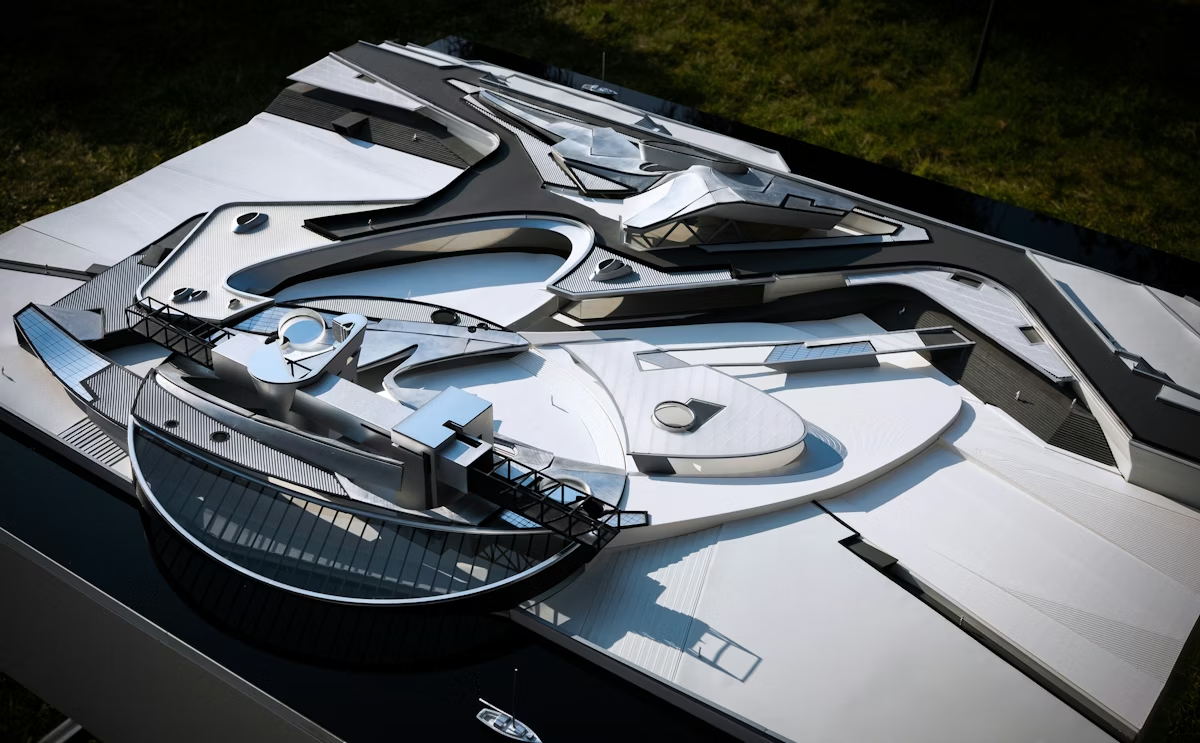

Perimeter Play by Paul Michael Davis Architects PLLC, Special Mention, Presentation Model, 2025 Vision Awards

Beyond their tactile appeal, physical models remain one of the most effective tools for understanding how a design actually works. Almost every architect has experienced the moment when a model, even a simple one, suddenly exposes a problem or confirms an idea with a clarity no drawing (whether analog or digital) ever managed.

Regal Dynasty Deluxe – The El Presidente Collection by Scott Specht, Finalist, Concept Model, 2025 Vision Awards

Certain spatial qualities become immediately legible when studied in three dimensions. Scale is one of them. Proportions that seem balanced on a screen can feel unexpectedly large or small when they exist as real volumes. Hierarchy is another. In a model, primary forms naturally assert themselves while secondary elements recede, revealing whether the design’s organizational intent is clear.

Adjacency and circulation also surface more honestly. Relationships that appear rational in plan sometimes feel disconnected when translated into physical massing, and transition spaces that seem minor on paper can take on unexpected importance when experienced volumetrically. Even the simple act of moving around a model reveals sequencing, orientation and sightlines in a way fixed digital viewpoints cannot replicate. (Even the infamous “turn it upside down” move many of us endured in school apparently had a purpose.)

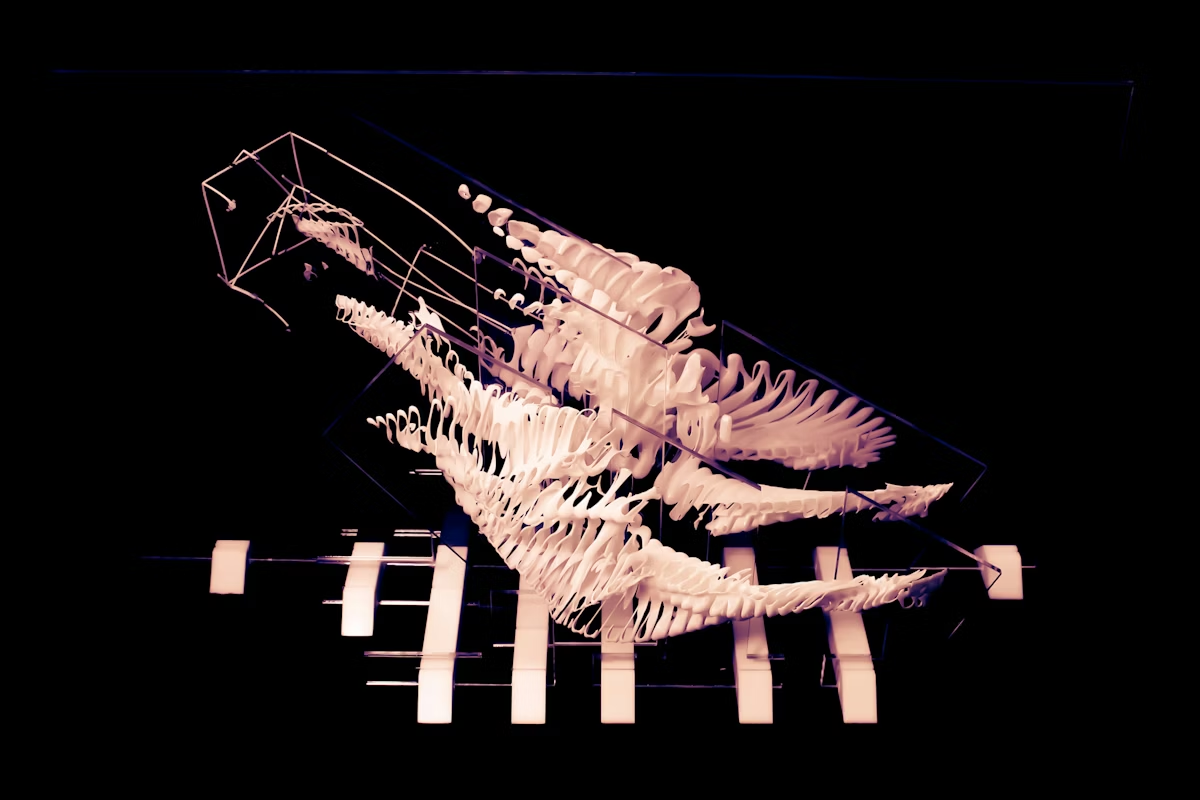

ENSEMBLE: Configurations of Objects, Forms and Spatial Relations by Julian Edelmann, Jury Winner, Presentation Model, 2025 Vision Awards

These insights influence how a building functions, how people move through it and how spaces relate to one another. Physical models expose strengths and weaknesses early, long before they become embedded in the design. In this sense, they serve as analytical tools that complement drawings and renderings, offering a level of spatial truth that is difficult to achieve through screens alone.

This is also why the earliest, roughest models are as important as the ones built for presentation, since they reveal the design’s intentions long before representation and good graphics smooth them out.

Digital Tools Expanded the Possibilities of Physical Models

Embodied Carbon by Masataka Yoshikawa – Lawrence Technological University, Jury Winner, Concept Model, 2025 Vision Awards

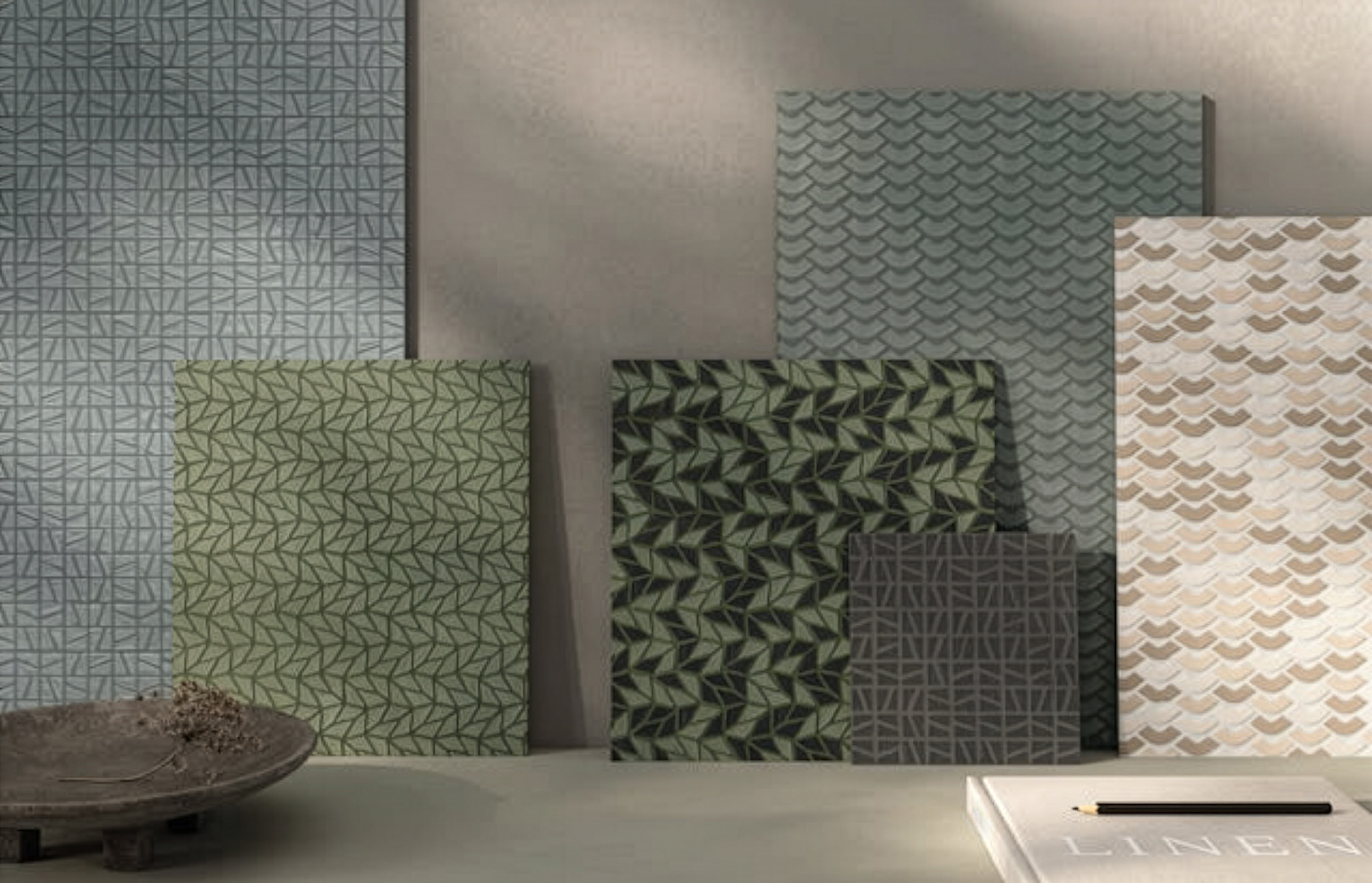

Even as digital technology introduces its own challenges, it has simultaneously expanded what physical model-making can be. Instead of replacing analog craft, contemporary tools have transformed it, introducing techniques and forms that were effectively impossible to build even a decade ago.

Laser cutters, CNC mills and 3D printers allow architects to explore geometries that would be too intricate, repetitive or time-consuming to craft by hand. Designers can prototype complex surfaces, modular assemblies or interlocking parts with a precision that manual methods cannot achieve. These components are then combined with materials like wood, acrylic, metal, plaster or soil, producing hybrid objects that merge exact fabrication with tactile, interpretive assembly.

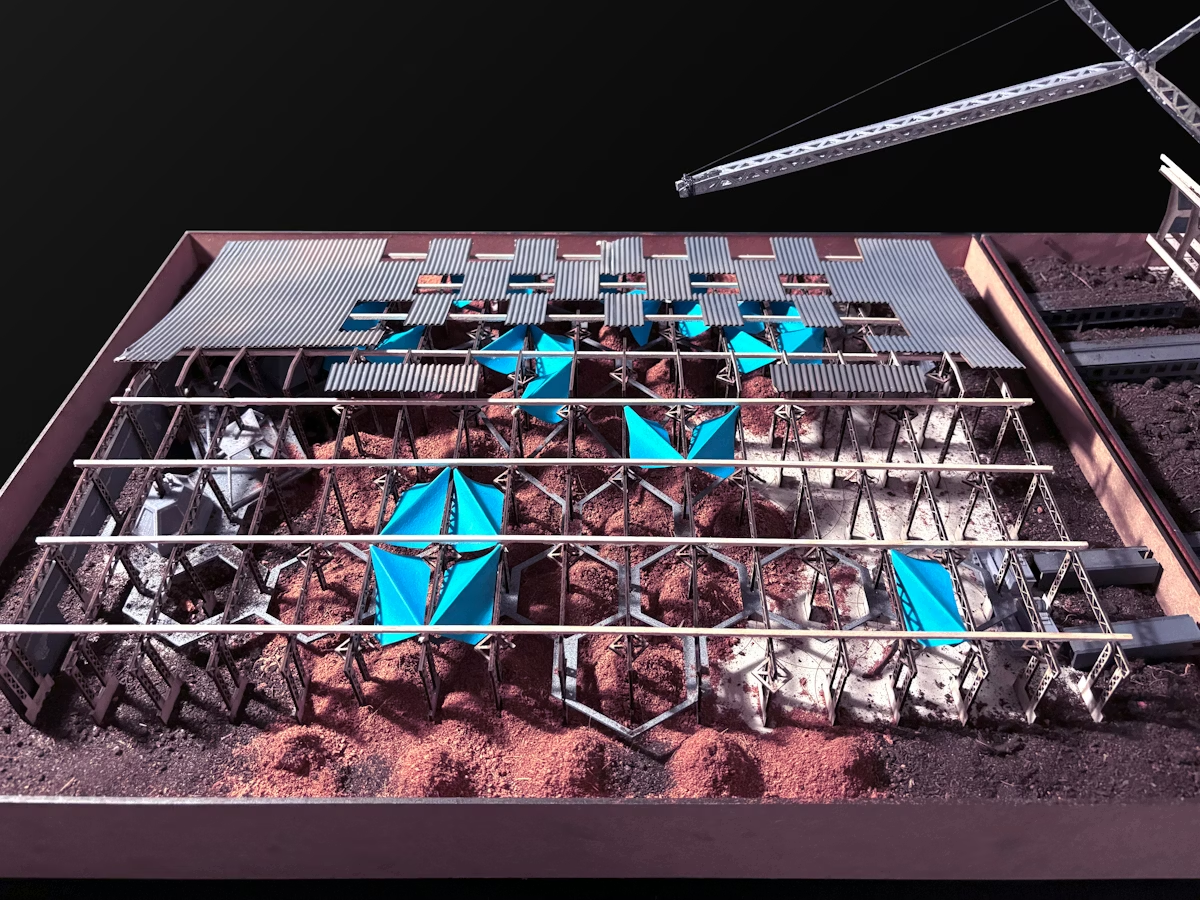

The Death and Life of Ultramafic Soil by Liu Yao, Finalist, Concept Model, 2025 Vision Awards

Digital workflows also make it possible to model ideas driven by information rather than imagery. A model may be produced from climate data, structural analysis, material behavior scripts or parametric systems, turning abstract datasets into something that can be handled, rotated and tested. In many cases, the model becomes less of a representation and more of a physical experiment, allowing architects to study performance, behavior and logic at a manageable scale.

Perhaps the most significant benefit of this post-digital approach is that it broadens what “model-making” can include. Models can test internal forces, layering strategies, mass-customized assemblies or complex curvature without requiring fully resolved technical drawings. They can also act as rapid prototypes that reveal how pieces connect, what tolerances are viable and how a form behaves when translated from a smooth digital mesh into real materials.

Why Models Will Always Matter

Data Democracy: The Memory Centre by Leo Wing Lok Lui, Finalist, Concept Model, 2025 Vision Awards

Physical models aren’t returning to the spotlight because digital tools failed, but because architecture works best when both coexist: digital tools for speed, physical making for truth. And in a moment when the software we use can generate endless iterations, a tool that offers a single, steady read on what the design is actually doing quickly becomes indispensable.

For all the promises of seamless workflows, the physical model continues to hold a place no digital tool has managed to replace. We won’t be getting rid of them any time soon (or ever, really) because they keep revealing things that drawings and renderings simply can’t. Plus, there is something oddly satisfying about seeing the medium we once cursed passionately become the one that brings presence back into focus.

The votes for the 2025 Vision Awards have been counted! Discover this year's cohort of top architectural representations and sign up for the program newsletter for future updates.

The post Analog Architecture: Why Designers Are Putting Physical Models Back in the Spotlight appeared first on Journal.