Lines of Thought: Why Architects Still Draw — and Why It Still Matters

The votes for the 2025 Vision Awards have been counted! Discover this year's cohort of top architectural representations and sign up for the program newsletter for future updates.

Recently, I was invited to give a lecture on Drawing Practices in Architecture. The catch? The audience was a rather large group of first-year students. While preparing for the presentation, a couple of questions came to mind: how do you explain something as complex and deeply ingrained in architectural culture to people who have been studying architecture for only two months, and, perhaps more importantly, how do you stress its importance in architectural practice – especially to people who know nothing of architecture?

Drawing is the architect’s bread and butter, and yet the common misconception is that it is merely a medium used to represent either the world that exists or the building that exists only in the architect’s mind. Architectural representation, however, is just one of the languages or modes of thought that drawing is capable of. It can also become very explorative, either through analysis or speculation. It can reveal relationships between conditions (material or immaterial), scales and narratives, all through the single act of drawing.

Drawings by Eugene Tan, Architectural Illustrator of the Year, 2025 Vision Awards

When discussing analytical drawing, the operative idea is “drawing to understand.” From detailed surveys of historic buildings to thorough site analysis plans that record sun paths, wind, vegetation, movement, smell and so forth. These drawings are all about documenting, measuring and clarifying conditions found on a site, a city, a landscape or a building. They are the working surface upon which a later design proposal or speculation may emerge. However, it has another equally important function: it opens up questions or — to use a more architectural phrase — threads of investigation.

A great example of such drawings is this year’s Vision Awards winner, Eugene Tan, as Illustrator of the Year. In his project description, he states, “My work focuses on representing architectural illustration as a form of dialogic design. I believe that good architectural representation can do more than act as a static method of instruction, but also serve as a mode of inquiry for the ‘creative user’.”

The Archatographic Map of the Incomplete Landscapes on Pedra Branca by Eugene Tan, Editor’s Choice Winner, Computer Aided Drawing, 2025 Vision Awards

His drawing of The Archatographic Map of the Incomplete Landscape plots the political and ecological significance of disputed islands in Pedra Branca. It is composed through a series of aerial views and multiple elevations to construct a comprehensive depiction of the island and its surrounding context. In parallel, the drawing challenges the island’s status as a political territory and proposes to transform it into a space for public enjoyment and environmental appreciation. Specifically, the archatographic map acts as both a survey and a critical instrument that tackles questions of ownership and ecology.

On the other hand, speculative drawing looks beyond what is there and asks, “What if?” It becomes a narrative device that constructs worlds in order to test things; it showcases environments – built or otherwise – that are often beyond the sphere of physical materialization. Zaha Hadid’s early paintings, the Archigram comics and the Superstudio collages exemplify the speculative lineage within architectural representation – one that remains remarkably alive in contemporary practice.

Nomadelle 2080 by Jimena Ruiz Sing, Jury Winner, Vision for Transport, 2025 Vision Awards

Nomadelle 2080 by Jimena Ruiz Sing for instance, is a project that suggests a very speculative and unorthodox vision for transport. It carries us to year 2080, when a major flood strikes the province of Limón, Costa Rica, devastating its central and coastal areas. Consequently, the population is forced to migrate to higher ground within the province. The design proposes a series of autonomous mobile vehicles that offer transportation throughout the flooded landscape as well as respond to the immediate social and economic activities. The vehicles also adapt to different types of terrain, with one distinct example being a banana processing plant that enables the transportation from the plantations to the Port of Moín, where the goods are prepared for exportation.

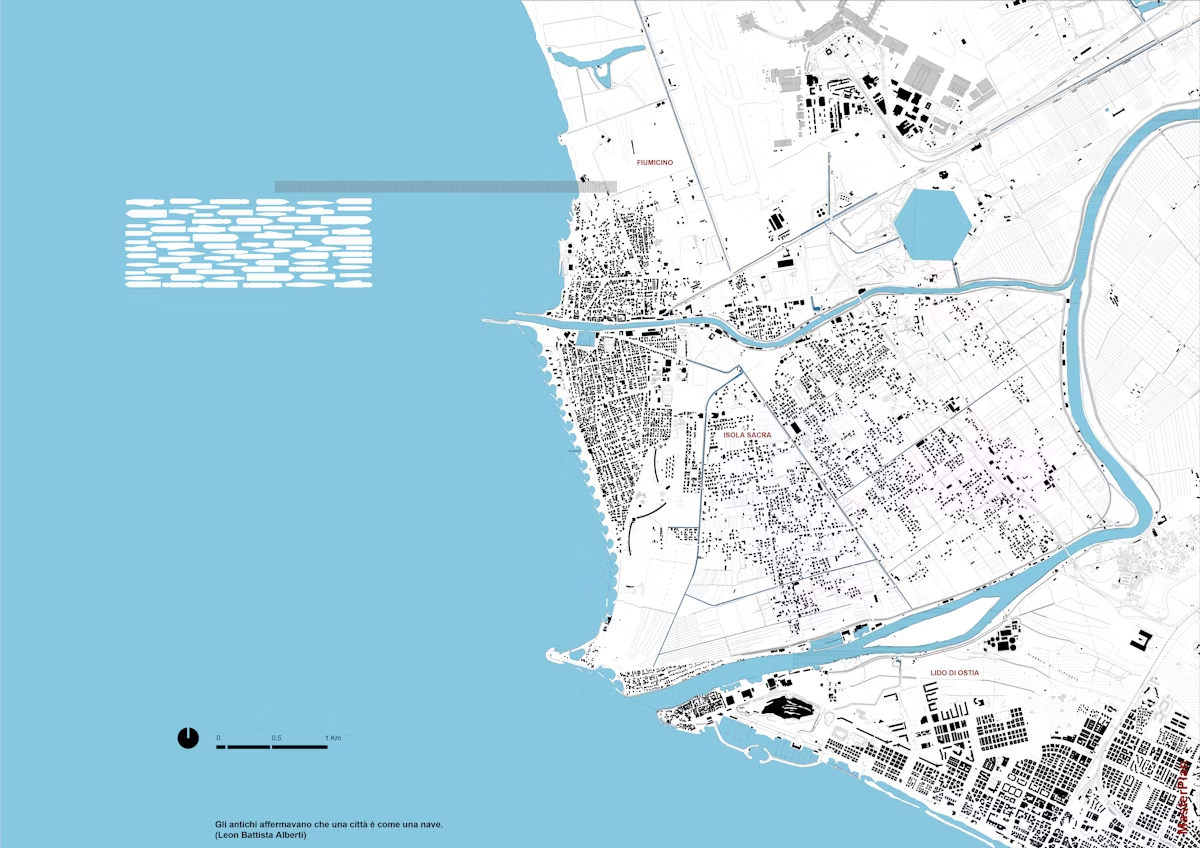

At a much larger scale, TERRAS MEDITERRANEAS a floating city for Rome by Studio Andrea Dragoni, reimagines a city as a ship. Portuguese author Josè Saramago, in his book, The Stone Raft, envisions that the Iberian peninsula detaches itself from the mainland and begins to sail towards an imaginary landing place. He conceives the open sea as the extension of Italian cities. In response, the project tests this speculation by drawing up a reconversion of large ships destined for decommissioning into small floating cities. Both projects act based on an assumption – a speculation of a flooded landscape or a drifting territory. They explore different ways of moving through a terrain or rebuilding future cities, all through the act of architectural drawing.

TERRAS MEDITERRANEAS a floating city for Rome by Studio Andrea Dragoni, Editor’s Choice Winner, Vision for Cities, 2025 Vision Awards

Whether the drawing is regarded as analytical or speculative is irrelevant. Although this distinction helps us articulate the many possibilities of architectural drawing, their relationship is far from binary. An analytical drawing can turn speculative, where measured data is transformed into an investigative act, and a speculative drawing can be grounded in research, based on real-world information or geographies.

Ultimately, the argument posed through this article is that drawing is not merely a tool of representation but rather a mode of inquiry. It is a fluid process that observes as well as invents facts and fictions, blurring the line between research and imagination. Within this continuum, architectural drawing becomes a form of research in its own right through the act of making, reminding us that drawing is not just about showing architecture, but about thinking architecturally.

The votes for the 2025 Vision Awards have been counted! Discover this year's cohort of top architectural representations and sign up for the program newsletter for future updates.

Featured Image: Nomadelle 2080 by Jimena Ruiz Sing, 2025 Vision Awards, Jury Winner, Vision for Transport

The post Lines of Thought: Why Architects Still Draw — and Why It Still Matters appeared first on Journal.