From Outsider to Icon: Frank Gehry’s Legacy (In His Own Words)

Architects: Want to have your project featured? Showcase your work by uploading projects to Architizer and sign up for our inspirational newsletters.

Frank Gehry’s recent passing has sparked a wave of tributes across the architecture world, and for good reason. Few architects have shaped contemporary culture quite the way he did (and even fewer have sparked as many arguments along the way).

Born in Toronto and based in Los Angeles, Gehry went from experimenting with plywood and chain-link fencing in his Santa Monica home to designing the very buildings that cities now use to brand themselves. Whether you loved his work, hated it or simply didn’t know what to do with it, you probably had an opinion. And that is precisely why he loomed so large.

Frank Gehry was many things, but he was never a neutral figure. His work had a gravitational pull that cities felt long before critics agreed on what to call it. Bilbao’s titanium wings, Disney Hall’s sculptural steel and the drifting glass forms of Fondation Louis Vuitton were all part of the same instinct: architecture that insisted on being noticed. Even his smaller projects carried that conviction that buildings don’t need to apologize for taking up space.

And Gehry himself was never shy about articulating his views either. Across interviews, documentaries and the occasional press-conference outburst, he gave us a surprisingly candid record of how he thought, worked and saw the world. And in a moment when the profession is trying to understand (or define) what his legacy really means, returning to those words feels like a fairly honest place to start.

On the emotional impact of architecture:

“I stood in front of a Greek statue called the Charioteer… it made me cry. And I thought: that’s what an architect should do — be able to create an emotional response with their work that lasts through the centuries. That’s what I try to do. I know that sounds pompous, but it’s a wish. It’s a hope.”

Vue du bâtiment de la Fondation Louis Vuitton (façade sud) et de l’entrée Bois de Boulogne; © Gehry Partners, LLP and Frank O. Gehry; photo by Iwan Baan, 2014

Gehry made this statement late in life, but it’s hard not to see reflections of it throughout his career. While many people in the industry (and outside of it) often reduced his work to pure spectacle, statements like this one shift the narrative a little. It’s clear that Gehry’s buildings weren’t created for the shock factor alone, as there were always attempts to tap into something that’s beyond surface impact.

Speaking with Architizer about Fondation Louis Vuitton (which was the venue of the 2023 A+Awards gala), Gehry described his first encounter with the site in a way that hinted at how seriously he took these moments. Beneath the spectacle, there was always a sensitivity to context and memory that guided him, even if that side of the story was rarely the headline.

On standing out and fitting in (depending on who you ask):

“I respond to every fucking detail of the time we’re in with the people we live with, in this place. So it’s all taken into account as best I can. You know, I believe that’s the most important thing to do — to live in the place and time you are in and what the issue is.”

Luma Arles by Gehry Partners, Arles, France; Photo by Sharon Tzarfati Photography

Gehry said this in a Dezeen interview about the Luma Arles tower, a project that immediately drew questions about scale, visibility and environmental responsibility. Many felt the building stood apart from its surroundings in a way that bordered on interruption. Gehry, however, described his choices as a response to the conditions of the moment, which suggests that his idea of context might have been broader and more fluid than what people expected.

Such a tension was visible in his Santa Monica house, too, the first project that truly announced him to the world (and launched his reputation for disruption). While his neighbors saw an intrusion, Gehry saw a reaction to the textures, rhythms and small collisions of the street. What appeared provocative to others seemed, in his view, like a straightforward engagement with what was already there.

These examples point to something that often gets missed when people critique his work. Gehry doesn’t respond to context in the traditional sense of matching forms or materials, yet he was responding to something. His buildings often register the mood of a place, the cultural noise around a project or the urgency of the moment in which it was made. It is not context in the textbook sense, but it is a kind of contextual reading all the same, one that explains why his work can feel disruptive to some and strangely truthful to others.

On his process:

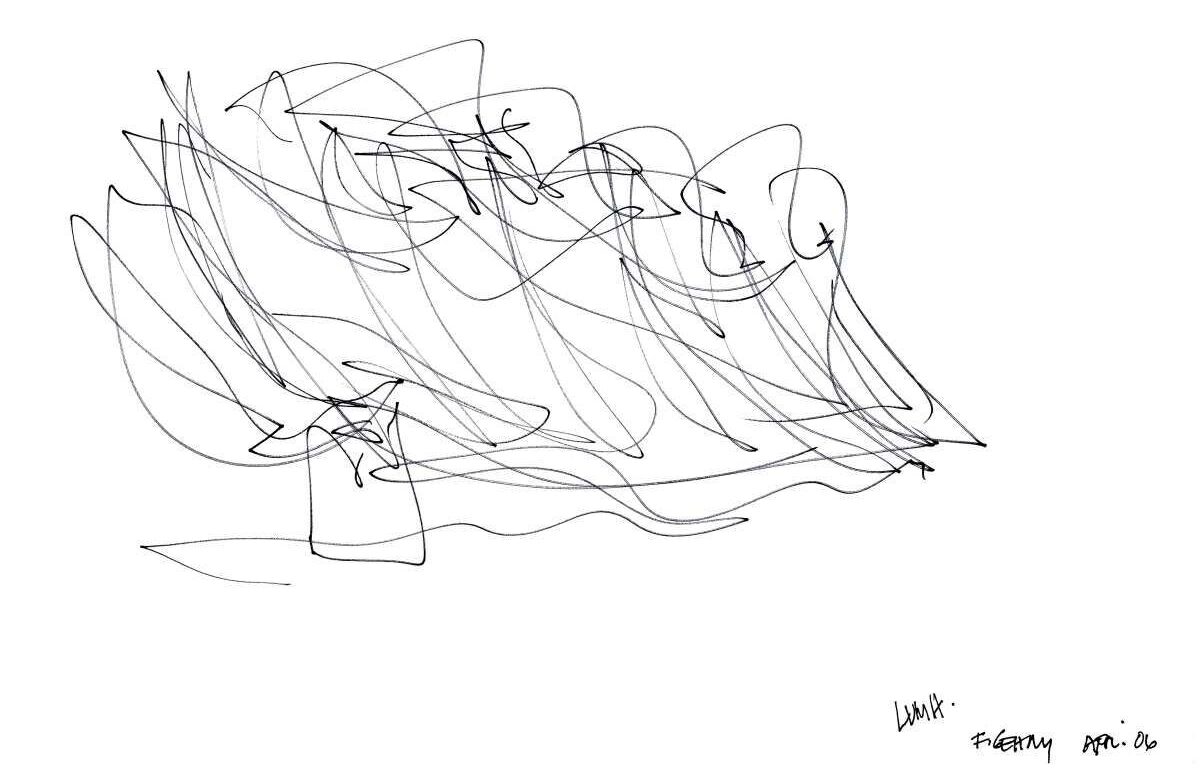

“Our process starts with a very detailed deep-dive into the client’s space needs, their budget and the zoning constraints of the site. We build a lot of basic block models exploring the three-dimensional functional diagram of the building. This makes it easy for the client to engage with the project and to give feedback to help drive design decisions. My sketches don’t come out of thin air. They come after we have decided on a general massing, and after a lot of conversation with the client about their aspirations.”

Vue générale du bâtiment de la Fondation Louis Vuitton (façade nord) depuis le Jardin d’Acclimatation; © Gehry Partners, LLP and Frank O. Gehry; photo by Iwan Baan, 2014

Early conceptual sketch by Gehry, 2006 © Frank O. Gehry

Even before the Simpsons episode, the public loved the idea that Gehry simply scribbled something wild on a napkin (or rather, crumpled the whole napkin) and let the software team turn it into a building.

What he described here, however, paints a different picture. The sketches come after the diagrams, after the zoning studies, after the conversations about what the building needed to do. His spontaneity was real, but it arrived late in the process rather than at the beginning, often as the final expression of a structure that was already deeply defined, at least in terms of function

This is perhaps one of the biggest ironies of Gehry’s career. The parts that looked the most chaotic were often the parts supported by the most groundwork. His gestures that were perceived as if done on a whim were simply the last layer of a process that was far more deliberate than his reputation suggested.

On the discipline behind the gesture:

“First of all, if you’re going to be an architect, you have to learn the craft. You have to learn how to build, you have to learn engineering, you have to learn how to be responsible to build something that doesn’t leak, that stands up, that doesn’t kill people. There’s a discipline you have to learn, for sure. Your personal spirit has to evolve into a language you create.”

Carol M. Highsmith, creator QS:P170,Q5044454, Image-Disney Concert Hall by Carol Highsmith edit, marked as public domain, more details on Wikimedia Commons

For all the attention on the curves and the steel, Gehry’s buildings depend on an extremely rigorous understanding of construction, engineering and risk. The Guggenheim Bilbao has stood through harsh weather and heavy footfall for more than twenty-five years. Walt Disney Concert Hall is still praised for its acoustic precision. Even his Santa Monica house has held up structurally despite its experimental materials.

The discipline he describes here is easy to overlook because the narrative around him often focuses on the gesture rather than the groundwork. Yet the longevity and performance of his buildings make it clear that the expressive language he developed was grounded in a technical foundation he took very seriously.

On wearing the criticism (literally):

“When Bilbao was presented publicly, there was a candlelight vigil against me… and there was a thing in a Spanish paper saying, ‘Kill the American Architect.’ … Once the building was built, I could live there for free. The same thing with Disney Hall — when it was first shown, they called it broken crockery, and now everybody thinks it’s great. So it takes a while.”

Gehry understood backlash almost as a phase of the work. The protests in Bilbao, the skepticism around Disney Hall and even the “Fuck Frank Gehry” t-shirts shirts circulating through the city (and apparently through his wardrobe, too) made it clear that public opinion rarely arrives in step with architectural intent. However, he didn’t treat this hostility as a wound so much as an inevitability of making something unfamiliar.

What happened afterward turned into what we now know as “the Bilbao Effect”, or the idea that a single building can shift a city’s economy, identity and global visibility.

It also became one of the earliest and clearest examples of what would later be called “starchitecture”. The term is often used dismissively, a shorthand for buildings designed to shock rather than serve, and many of the criticisms attached to it are not without merit. Yet Bilbao defied that narrative. It suggested that, under the right conditions, an ambitious cultural building could do more than dominate a skyline. It could redirect a city’s trajectory, revive its economy and give residents a renewed sense of place.

Starchitecture may still be controversial, but Bilbao demonstrated that its value cannot be reduced to spectacle alone. In some cases, the bold gesture produces an impact that goes far beyond the surface.

On the state of the industry:

“Let me tell you one thing,” he said. “In the world we live in, 98 percent of what gets built and designed today is pure shit. There’s no sense of design nor respect for humanity or anything. They’re bad buildings and that’s it.”

This response to a journalist’s question has become one of Gehry’s most quoted remarks, partly because of the casual profanity, but mostly because it feels uncomfortably accurate. Even though he later blamed the outburst on jet lag and many read it as pure provocation, it feels like there is a clear thread of honesty running through it.

One could imagine that for Gehry, the real problem with most buildings was not that they were ugly. It was that they felt empty. He spoke so often about architecture carrying intention and emotional weight that it’s hard not to wonder whether he viewed the absence of those qualities as a kind of professional failure. Indifference seemed to offend him far more than eccentricity ever could.

This might also explain why he so frequently returned to the importance of engineering, construction and responsibility before personal expression. If that foundation slips, architecture can drift into something corporate or technically polished without offering much in return. His comments don’t say this outright, but they point toward a discomfort with work that functions smoothly yet has nothing to say.

His buildings may have been polarizing, but they were never indifferent. In the end, his work came from a belief that architecture should register on a human level, even when that stance risked backlash.

On his legacy:

“Legacy is best left to others to determine. Time is the ultimate arbiter of success. I just try to do my best on every project that I work on. It means listening a lot… and being curious about the activities that will be taking place in the building.”

Gehry may have left the question of legacy for the future, but the world has already begun to answer it. His buildings changed cities, stirred debate and pushed the discipline forward. What his work becomes in the decades ahead is harder to predict. It may settle into the canon, it may spark new reactions, it may even be reinterpreted through lenses we don’t yet have.

That sense of possibility however, might be the most fitting legacy of all.

Architects: Want to have your project featured? Showcase your work by uploading projects to Architizer and sign up for our inspirational newsletters.

The post From Outsider to Icon: Frank Gehry’s Legacy (In His Own Words) appeared first on Journal.