Form Follows Freedom: Relaunching Foster + Partners’ Sainsbury Centre

Architizer’s Vision Awards are back! The global awards program honors the world’s best architectural concepts, ideas and imagery. Preregistration is now open — click here to receive program updates.

It’s not every day you walk into a gallery or museum and realize you’re part of the exhibition. But it’s hard to feel like anything else when standing inside a glass box next to a priceless international art collection, being ogled by other pieces and members of the public alike.

This rare epiphany evokes a strange sense of empathy and even sympathy for art as objectified by industry and society. You begin to feel sorry for figures like the Mona Lisa and finally understand the pain of Edvard Munch’s tortured figure in The Scream. How does it feel to be stared at and glared at by strangers all day, every day? (Maybe with the exception of Mondays, when most British cultural institutions are closed.)

Whichever way you’re looking at whatever it is you’re looking at, the Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts presents it very differently. One case in point is the chaise longue to lie in and share secrets up close and personal with portraiture.

Completed in 1978 and funded by the family behind one of the UK’s biggest supermarket chains, even the institution’s inception was against the grain. While enthusing over the anti-establishment roots of this inimitable facility, Jago Cooper, director since a 2023 relaunch, tells us the benefactors took just one piece of advice before the project began: If you’re going to build a gallery unlike other galleries, don’t listen to anyone from the art world.

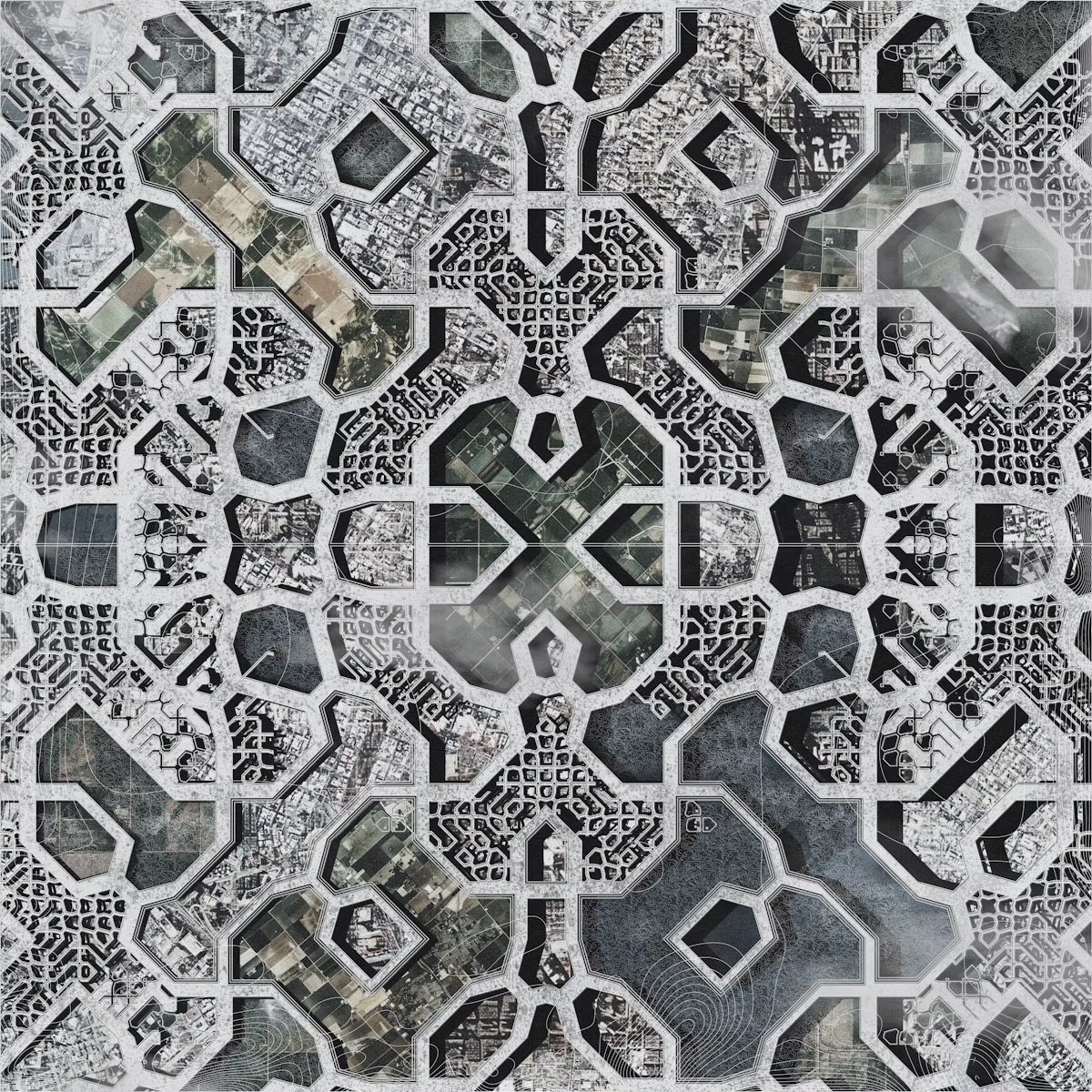

Aerial view of The Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts by Foster + Partners, Norwich, United Kingdom

Instead, they looked to then-rising architects Norman Foster and the late Wendy Cheesman. The Norwich site, which sits on the University of East Anglia campus, is the first of many public buildings from the behemoth master planner and was never going to go quietly. The design reflects and enacts the institution’s radical programming premise.

Among the statement features, 30-foot (9-meter) floor-to-ceiling glass walls and full-size trees in the main exhibition space responded to the modernist ideal of bringing nature and the built environment together. The internal foliage has since gone, but the location, in the midst of the center’s sculpture park and those vast windows, remains and continues to achieve the desired results.

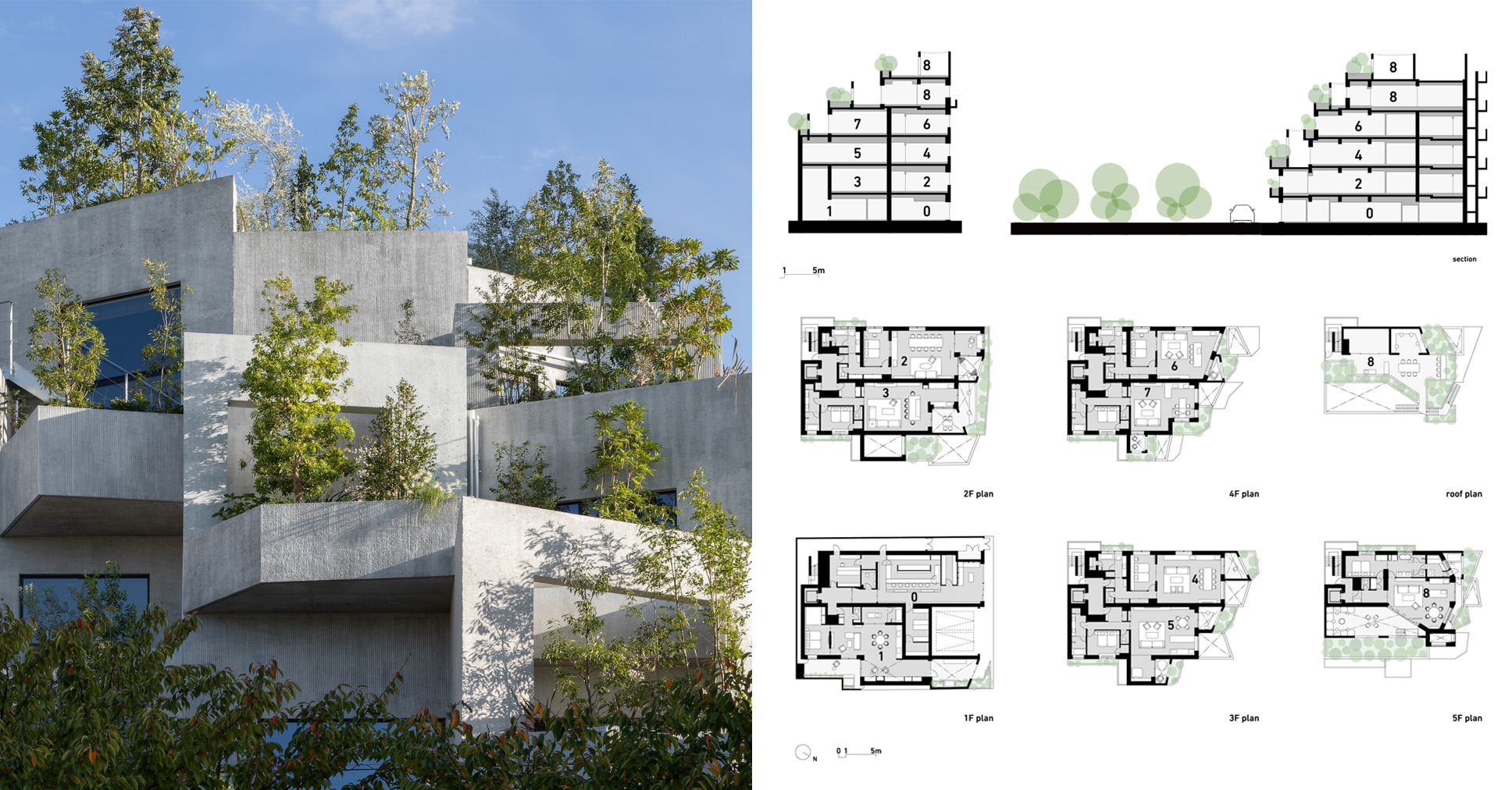

The Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts by Foster + Partners, Norwich, United Kingdom

“Museums, art, and all industries have loads of norms that become established,” says Cooper. “The genuine people who come with a fresh set of eyes and are not just looking at the structure and trying to change it, they are starting something with a completely blank canvas.

“There is a fundamental difference between trying to change an institution or a way of thinking, trying to change something that already exists, and when you start with a blank page from scratch,” he continues. “Because then you wouldn’t start off on the same pathway; it’s totally different.”

Sadly, the original cantilever system has also been confined to history; it would have moved as hours of the day passed, casting the interior in a different light depending on the sun’s position. However, the most unique aspect of the project is more difficult to see at first glance. When it opened, the Sainsbury Centre was Britain’s largest open plan space ever realized, with an overall floor area of 77,500 square feet (7,200 square meters). Measuring 490 feet (150 meters) in length, it’s as vast as an aircraft hangar, and there are near-endless ways it can be configured, depending on the use cases.

The Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts by Foster + Partners, Norwich, United Kingdom

Although there are some distinct spaces, including those on the lower level, the building is dedicated to a single area for the most part. Here, there are no predetermined routes or hierarchy of work. Everything is equal, and visitors are free to explore as they choose. And even the more siloed exhibitions are not ‘ring-fenced’ like standard galleries. The UK is lucky that many public museums and cultural destinations are free to enter. Still, visiting and special programs often charge a premium and are found in clearly delineated zones.

At the Sainsbury Centre, visitors pay what they feel, and the whole place is dedicated to big, overarching questions that run for seasons. These are not really separate exhibits but parts of an overarching theme. Why Do People Take Drugs? What Is Truth? And, currently: Will The Seas Survive Us? The big quandaries are honed down from open calls on social media. Shortlists then get posted in staff areas and voted on by everyone there. It’s pretty much fair game, albeit with a couple of caveats.

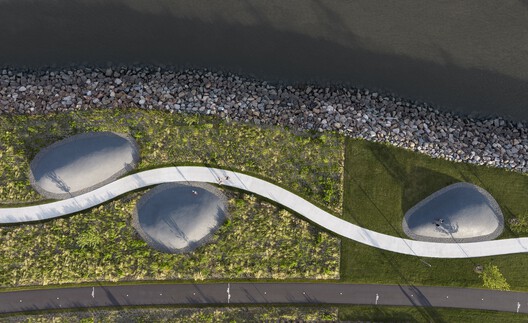

Becoming a work of art inside The Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts by Foster + Partners, Norwich, United Kingdom | Photo by Kate Wolstenholme

“If you’re going to empower people to make their own decisions about what they want to do, this goes to the bigger question of the museum itself — why do museums exist? Well, it’s to help society. So, therefore, the starting point is not a question that arises from the world of art or art history or archeology or anthropology; it’s the sort of question all people everywhere in society want an answer to,” Cooper explains before moving on to how the building itself facilitates the Sainsbury Centre approach.

“You basically create an open-plan labyrinth where the art isn’t on a wall; it’s in this three-dimensional space. Then, you choose your own pathway through that space, and all the art is in cultural dialogue across space and in that space. So, it means that you take ownership of your own journey through that space, and it’s very empowering to the visitor. And then the entrance is discrete — not too confrontational,” he tells us.

The Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts by Foster + Partners, Norwich, United Kingdom | Photo by Kate Wolstenholme

Sometimes, you need to be reminded we’re just talking about a large metal box with windows. But that’s precisely the point. Minimalist in the pure sense, by completely ignoring what remains the modus for galley design, evident everywhere from the British Museum and the Louvre to Tate Modern, Foster’s blueprint presents a bold challenge for any arts center: remove distractions, free up interpretations, and let the work speak for itself, on its own terms. Arguably, it is the greatest litmus test for the quality of the collection and thematic concepts.

“You can walk in any direction, go anywhere, and work might even force you to change your bodily position. So because the art isn’t on a wall, and you’re not walking down a corridor or going into a rectangle and then walking around the edge of the room, because it’s in this three-dimensional space where you’re walking through and around it, you’re changing your bodily position. You’re bending down, you’re up, you’re looking there,” says Cooper. “[You’re] not feeling like you’re on a journey just following, you know, the highlights tour of a museum.

“In nearly all other museums, there’s a big grand entrance, and you sort of go up steps into them, and then they have these hallways, and there’s a pathway around them into different galleries, which divide up either on chronology or impressionism or other big words,” he adds. “This is anything but that.”

Architizer’s Vision Awards are back! The global awards program honors the world’s best architectural concepts, ideas and imagery. Preregistration is now open — click here to receive program updates.

The post Form Follows Freedom: Relaunching Foster + Partners’ Sainsbury Centre appeared first on Journal.