Fifty Shades of Brown: An Architect’s Guide to Santa Fe, New Mexico

Architects: Want to have your project featured? Showcase your work by uploading projects to Architizer and sign up for our inspirational newsletters.

One afternoon this August, while vacationing in Santa Fe, I was walking through a residential neighborhood when I was interrupted by a young man in overalls.

“I need your help, brother,” he said in a reedy New Mexico accent. “Is this color OK?”

I removed my AirPods and replied, “Huh?” It took me a moment to piece together that the man was a house painter and was pointing to a home that he was working on.

My first thought was that he was joking. The house was being painted brown — just like every other house on the block. Really, nearly every building in Santa Fe was a similar shade of brown, and virtually all of them had the same heavy adobe (or faux adobe) walls. But when I looked more closely at this painter, I saw he was serious. More than that, he was concerned.

“I think it’s too orange,” he said. “The owner picked this color, and I told him it was too much.”

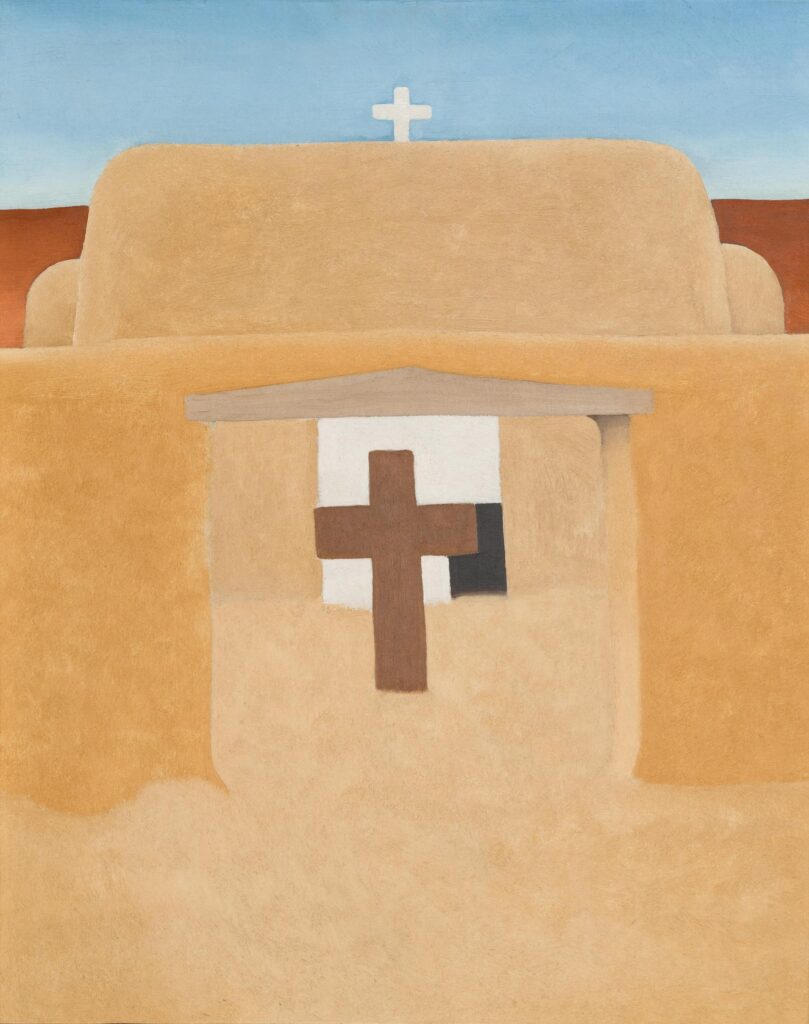

Longtime Santa Fe resident Georgia O’Keeffe is among the most famous admirers of adobe architecture. This painting titled “Gate of Adobe Church” was completed in 1929 and resides at the Carnegie Museum in Pittsburg. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

I squinted a bit and thought that maybe it was more orange than its neighbors, but I couldn’t really tell. Then I realized that this painter, who presumably lived in Santa Fe and worked on houses here often, was likely much more sensitive to slight differences in the color brown than I was. Familiarity had made him a kind of connoisseur. It isn’t true that the Inuits have 50 words for snow — this is an urban legend — but the story speaks to a general truth. Specialists see differences that the general public do not.

I told the painter that I thought the color looked great, but privately I knew that I wasn’t the one to ask. I couldn’t see brown like a local.

There are very few cities in the United States as architecturally cohesive as Santa Fe. This is thanks to the absolute dominance of the Pueblo Revival Style of architecture in commercial, government and residential buildings. (Even the Trader Joe’s here is Pueblo Revival). And while one could complain that this makes the city homogenous, it is also makes it distinctive. This is a rare quality at a time when people are complaining about a global urban monoculture, where the architecture in cities as far flung as Manhattan, Riyadh and Singapore appears interchangeable. The new buildings that go up in these places are often very unique, but they also rarely speak to anything specific in their environment.

Santa Fe proves that there is beauty in architectural homogeneity. The downtown area especially, near the Plaza, is truly magical, featuring a number of architectural gems. The individual stories of these buildings help paint a picture of the Pueblo Revival Style, which surprisingly has roots outside the American southwest.

View of La Fonda Hotel from the southwest. Photo by Atakra, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

An architectural tourist in Santa Fe should first stop at La Fonda on the Plaza, a hotel that contains all the hallmarks of the Pueblo Revival Style. Just like the historic Native American adobe buildings on which the style is modeled, such as the majestic 1,000 year old Taos Pueblo — also a must for travelers to New Mexico — La Fonda features stepped massing, rounded corners and, of course, heavy battered walls. I believe these are stucco, which is often used to simulate the appearance of adobe.

For a first class hotel, La Fonda is quite austere on the outside. Small projecting wooden beams called vigas along with the stepped massing and contours in the facade provide enough visual variety to offset monotony. (It should be said, not all Pueblo Revival buildings are so lucky. Many pueblo houses succumb to blobishness).

The current iteration of La Fonda opened in 1922. It was designed by architect Isaac Rapp, who is known as the “father of the Pueblo Revival Style.” This is an important point: while Santa Fe has been continuously inhabited by Europeans since 1609, it was not until the 20th century that they adopted a “revival” style to simulate the appearance of both old mission buildings and the Native American pueblos on which the mission buildings were themselves modeled.

The current predominance of the Pueblo Revival Style has been enforced by 20th century legal ordinances, especially a 1957 ordinance drafted by a committee led by architect John Gaw Meem IV that mandated that all buildings in Santa Fe’s historic district be built in the “Old Santa Fe Style,” defined as “so-called Pueblo, Pueblo-Spanish or Spanish-Indian and Territorial styles.” This ordinance remains in effect, meaning that the visual cohesiveness of Santa Fe is the result of deliberate policy. It’s not just the “authentic” way that people happen to build in this part of the country, which I had somewhat assumed when I first encountered the house painter on a Santa Fe street.

One other interesting detail: Isaac Rapp, who is credited with creating or at least codifying the Pueblo Revival Style, was not from the southwest. Rapp was from Orange, New Jersey — about twenty minutes from where I live — and learned his trade in Illinois. The Pueblo Revival Style is thus an outsider’s interpretation of regional motifs. It is not something organically rooted in New Mexico. This fact might seem banal to some, but for me it unlocked a new way to think about what regional styles are really about.

Modest in size, yet exquisitely proportioned, the Loretto Chapel is the most beautiful building in Santa Fe. It is also said to be the first Gothic building constructed west of the Mississippi. Photo by Camerafiend, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

The most beautiful building in Santa Fe is ironically not built in the Pueblo Revival Style. The Loretto Chapel is the first Gothic church constructed west of the Mississippi and it has all the hallmarks of that style: spires, buttresses and stained glass windows. It was built in 1873 from locally quarried sandstone, giving it a dusty appearances that allows it to cohere with its pueblo surroundings. In fact, the beauty of this building owes much to the fact that it stands out from its environment, but not like a sore thumb. It allows one to really appreciate and notice the Gothic details, which would be harder to do if the chapel was situated in a more visually busy environment like New York, my city, which contains hundreds of beautiful churches that are passed by each day without notice.

Inside the chapel is one of Santa Fe’s most popular tourist attractions: the miraculous staircase. According to legend, the sisters at the chapel wanted a new staircase to reach the choir loft. They prayed to St. Joseph, patron saint of carpenters, for nine days. On the tenth day, a mysterious man appeared with tools and building materials. Over the course of a few days, he fashioned a magnificent spiral staircase out of wood that wasn’t native to the area. In its original incarnation, the staircase had no railing and appeared as a surreal floating helix, a stairway to heaven. The man then vanished as suddenly as he had come, accepting no payment for his work.

The origins of the “miraculous staircase” are shrouded in legend. Originally, this staircase had no railing. Photo by Christopher Michel, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

People like to think of the built environment as something that just arrived, like the staircase at Loretto Chapel. And it is true that great buildings often carry an air of inevitability, as if they were simply meant to exist just where they are. However, life doesn’t really work that way. The distinctive Southwestern aesthetic of Santa Fe is something that was deliberately manufactured in the 20th century, spearheaded by an architect from New Jersey of all places.

If there is a lesson to all of this, I think it is a hopeful one: namely that our cities are nothing more or less than what we decide to make them.

Architects: Want to have your project featured? Showcase your work by uploading projects to Architizer and sign up for our inspirational newsletters.

Cover Image: Daniel Schwen, “Adobe Pueblo Revival Architecture in Santa Fe, NM,” 2008. CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The post Fifty Shades of Brown: An Architect’s Guide to Santa Fe, New Mexico appeared first on Journal.