Architecture 101: What Is Sustainability in Architecture and Design?

Low carbon, nature positive, planet-friendly: brush up on the basics of what makes sustainable architecture sustainable. The post Architecture 101: What Is Sustainability in Architecture and Design? appeared first on Journal.

Architizer's 13th A+Awards features a suite of sustainability-focused categories recognizing designers that are building a greener industry — and a better future. Start your entry to receive global recognition for your work!

Net zero. Carbon neutral. Nature-friendly. Future-ready. Green. Pro-planet.

Whatever industry you’re in, there are no end to the buzzwords and top-line phrases we use to imply and infer actions that directly benefit the Earth, slow and mitigate the damage human civilization has been causing for a few centuries now.

Each can be considered a subheading beneath the unwieldy label of ‘sustainability’ — a word that literally means the ability to maintain something at a constant rate or level, indefinitely. But, while many of the myriad tags are essentially pretty meaningless, there’s no escaping from the truth. People need up-skilling in the art of not destroying the environment, upon which their own existence depends.

This is particularly true of architects and designers, the professionals tasked with creating cities and objects, buildings and items, of the future. Currently, the built environment accounts for 40% of all carbon emissions, and this figure remains stubbornly high. Progress is only be guaranteed when we wrap our heads around what it sustainable development really means. Here’s a 101 in green design and architecture to start us off.

Characteristics of Sustainable Architecture

Bundanon Art Museum + Bridge by Kerstin Thompson Architects, Illaroo, Australia | Jury Winner, Architecture +Environment; JuryWinner, Sustainable Cultural Building, 11th Annual A+Awards

What are the benefits of sustainable architecture?

It’s simple maths really. Without reducing our environmental footprint and making buildings — along with everything else — more nature and climate-friendly, the continued development of society risks destroying bringing about an end to civilization. So the benefit of sustainable architecture is avoiding self-annihilation.

Digging deeper, there are key ‘wins’ with sustainable architecture. Carbon emissions and other airborne pollutants are usually significantly lower with sustainable approaches. Often, fewer resources are used, with waste and — potentially — cost coming down as a result. These projects frequently place a high value on natural assets, too. And given green space, trees, plants and wildlife are proven to improve human health and mental health, it should go without saying this is another major plus point.

What is embodied carbon and why does it matter for architectural sustainability?

Embodied carbon refers to the greenhouse gas emissions produced during the design, construction and completion of a structure, and then any physical parts required to keep it standing. Breaking this down into Upfront (emissions up to the point the building becomes operational, in-use — day-to-day maintenance) — and end-of-life, meaning carbon footprint of demolition and deconstruction, reveals how big a deal it is.

Embodied carbon is hugely important for architecture to be truly sustainable because as we transition to renewable energy sources and operational footprints come down, most emissions associated with buildings are more likely to be a form of embodied at the construction stage. We’re still some way off perfecting truly affordable green concrete, which is a big issue in tackling this. Nevertheless, as regulations tighten, embodied carbon in the materials and creation of new structures will be more important than ever.

Gaia by RSP Architects Planners & Engineers, Singapore | Jury Winner, Sustainable Institutional Building, 12th Annual A+Awards

How important are regenerative and eco-friendly materials in sustainable design?

If using lower carbon materials is pivotal to tackling the climate crisis, then using regenerative and ‘eco-friendly’ products takes this one step further. Regenerative materials usually refer to anything that can contribute positively to a ‘right-carbon’ future, actively bringing down emissions and self-maintaining.

Interestingly, materials such as biochar, hemp, bark, cork, straw and bamboo are now considered at the bleeding edge of the regenerative revolution, but actually have more ties to historic, localized and indigenous construction methods than (almost) anything the 20th century gave us.

It is also crucial to consider that just because something is technically regenerative doesn’t mean it is planet-friendly. We need to note where materials are sourced from, how responsibly feedstocks were cultivated, and consider how alternatives measure up. The debate over recycled steel is a good example of this — technically regenerative, yet anything but ecological.

What role do adaptive and modular spaces play in sustainable design?

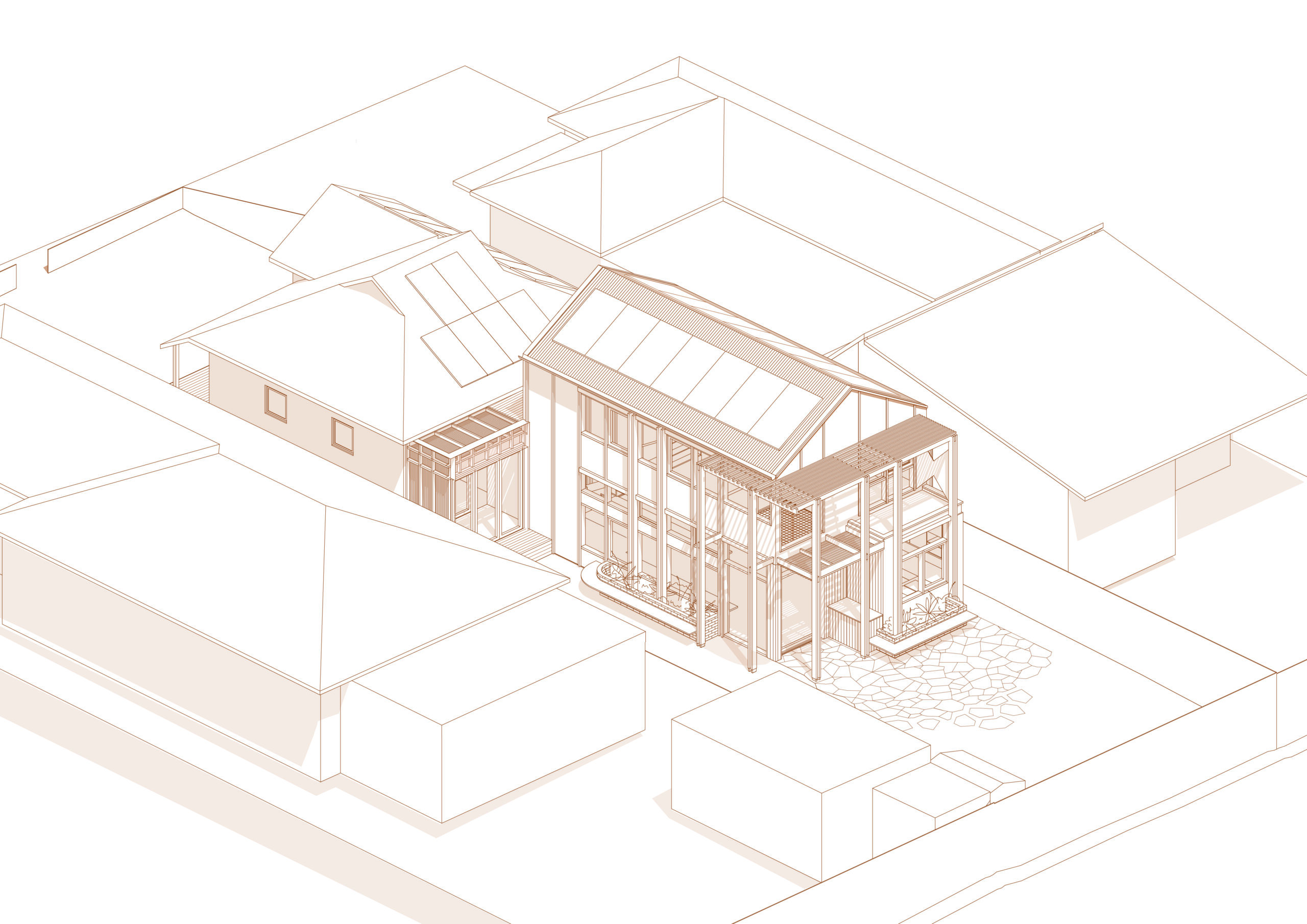

Adaptive architecture refers to the creation of buildings and structures that can adapt to and exploit traits in their environment. Passive heating and cooling systems could be one example. A living roof, which develops in response to climate conditions and species interactions, is another.

Sometimes, ‘adaptive’ relates more to the connection between inhabitants and users and buildings. Like designs that purposefully address accessibility for people with particular needs.

In contrast, modular means “employing or involving a module or modules as the basis of design or construction”. This means building something from smaller parts, often pre-fabricated then brought to site as a series of ‘complete’ parts, at which point it’s pieced together.

This isn’t always a sustainable option, but often results in less embodied carbon from production processes as labor times are reduced, fewer trips are needed to transport materials, and completion times are quicker. There’s often less waste, too, as materials can be precision prepared in specialist facilities, rather than cut to fit mid construction.

Manshausen – Two Towers by Snorre Stinessen Architecture, Steigen, Nordland, Norway | Jury Winner, Architecture +Environment; Popular Choice Winner, Sustainable Hospitality Building, 12th Annual A+Awards

How can biophilia, or incorporating plants and nature into buildings, help with sustainability?

Biophilic design has one core purpose — reconnecting people with nature by looking to nature for guidance on how to approach developing, improving or inventing solutions.

If we want to state the obvious, this is a fundamental principle of sustainable architecture because the blueprint is Earth itself, which has evolved systems capable of sustaining life for hundreds of thousands of years at a time without biosphere change.

Natural light and ventilation, engaging with the existing landscape, living walls, planted roofs and the use of eco-friendly, grown materials all fall into this category. By simulating the way plants have evolved to become self-sufficient but also net positive contributors to the planet, we can produce far more environmentally friendly buildings.

History of Sustainable Architecture

What is the history of sustainable architecture?

Sustainable architecture almost predates architecture itself. Traditional, rudimentary, ancient building methods were all sustainable by their very nature due to the materials available. So, despite their 21st century positioning, eco-friendly buildings are really mimicking and mirroring, or at least replicating the impact of what we were doing millennia ago.

The expansion of the Industrial Revolution, and the advent of the age of mass-production really marked the turning of a tide towards far less sustainable building practices. Modernism during the mid-20th Century then ushered in a period of ‘holistic’ architectural theory in some regions and circles, giving rise to today’s combination of au naturel solutions, ecological innovation and high-tech sustainability.

Examples / Case Studies

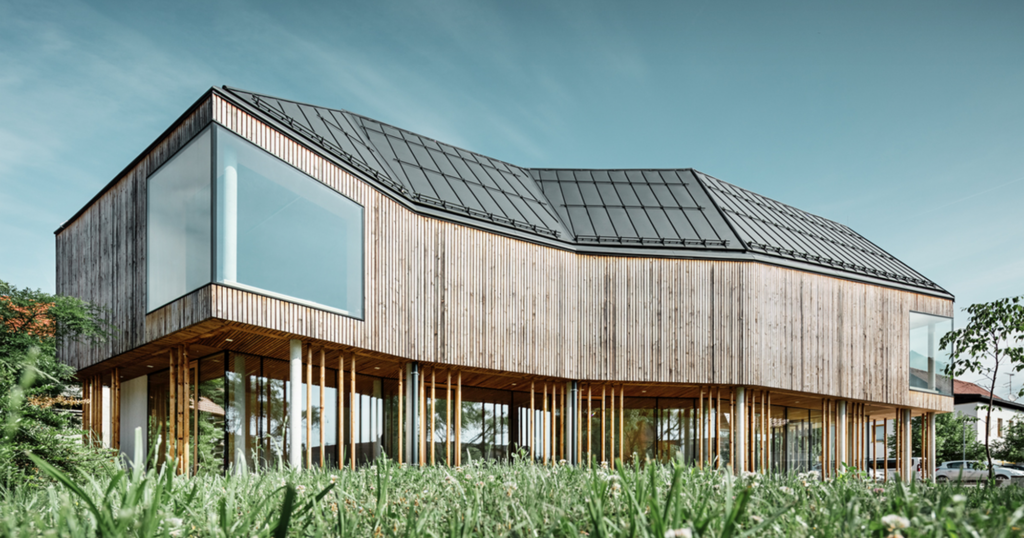

Life Cycle by Steffen Welsch Architects, Coburg, Australia | Popular Choice Winner, Sustainable Private House, 12th Annual A+Awards

What certifications exist to establish standards for sustainable buildings?

LEED – Leadership in Energy & Environmental Design

BREEAM – Building Research Establishment Environmental Assessment Method

WELL Building Standard – Certification based on human health and well-being in relation to a building

Green Globes – Green Building Initiative certification and rating system

Living Building Challenge – Certification of sustainable design and construction leading to net positive impact

DGNB – Measurement of a building’s effect on ecology, economy and society

Energy Star – US Environmental Protection Agency certification for operational energy efficiency

National Green Building Standard – rating and certification of homes and apartments for energy, water, maintenance, indoor environmental quality, more

Passivehaus Standard – Certification designating a home as being environmentally ‘passive’, indicating no or positive impact

Fitwel Standard – Focused on the health and wellbeing effects of apartments, retail and commercial buildings

Google Borregas by MGA | MICHAEL GREEN ARCHITECTURE, Sunnyvale, California | Jury and Popular Choice Winner, Architecture +Workspace; Jury Winner, Architecture +Wood, 12th Annual A+Awards

Which architects are associated with sustainable architecture?

The list could be longer, but here are a few distinguished names:

Kunlé Adeyami is an architect, designer and development researcher at NLÉ Works in the Netherlands, and the mastermind behind the Makoko Floating System — an adaptive, regenerative, low carbon solution to rapid population growth in coastal areas of developing countries facing the brunt of the climate crisis.

Michael Green is a Canadian architect and founder of Michael Green Architecture. In addition to authoring books on mass timber construction, he is also a vocal advocate of revolutionizing the AEC industry through material specification and design choice, drawing critical attention to the term “sustainability” itself.

Alexandra Hagen is CEO of Swedish sustainable architecture powerhouse White Arkitekter and has led on a number of iconic timber construction projects in northern Europe, a snowball’s throw from the Arctic Circle.

Mariam Kamara, founder of Atelier Masomi, considers local aesthetics, histories, societal attributes and environmental traits in every decision, informing use of materials such as glass and steel in projects across her Niger homeland and beyond — one of innumerable countries now on the frontline of climate change.

Edward Mazria has a hugely impressive portfolio of global projects and 40 years of sustainable practice behind him. In more recent years, he founded Architecture 2030, a pro-bono entity looking to transform the built environment into a net positive carbon contributor.

Pablo Sendra, in the bestselling Designing for Disorder, argues that the built environment’s liveability depends on its evolutionary qualities. Simply put, sustainable places are made to adapt and change roles as our needs evolve.

What are famous examples of sustainable architecture?

We’ve already mentioned headline-grabbing award-winners like the Makoko Floating System and Sara Kulturhus. But the Architizer archives are full of examples — hence a dedicated section of Sustainability Categories in Architizer’s A+Awards Program.

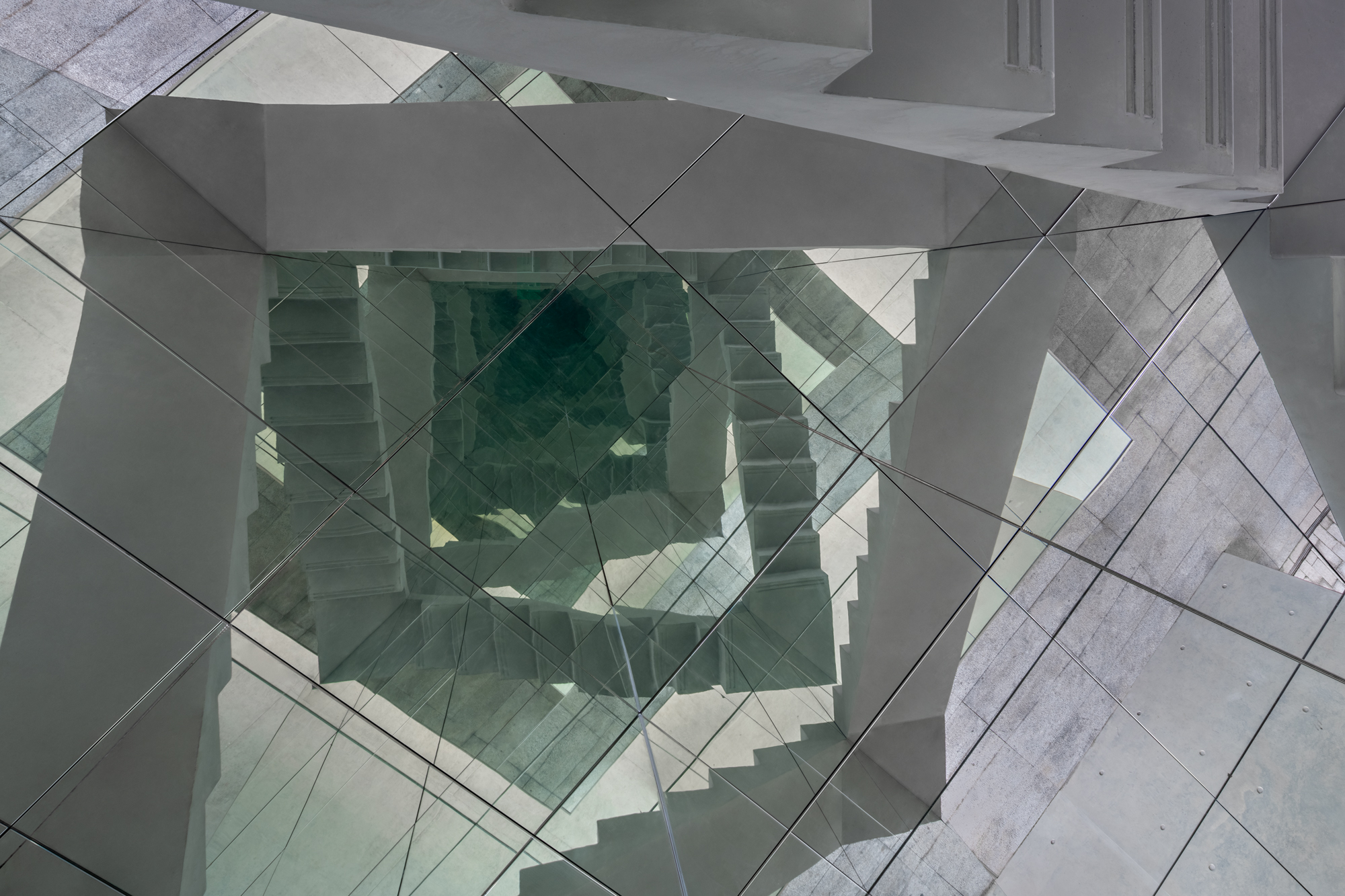

Past winners include commercial buildings like Oslotre Arkitekter’s HasleTre, Amazon HQ2 at Metropolitan Park by ZGF Architects and Foster + Partners Ombú, cultural institutions like the Bundanon Art Museum + Bridge by Kerstin Thompson Architects and the Echo building at TU Delft by UNStudio.

Not to mention private houses such as Sumu Takushima by tono.inc, and Shore House. This is before we come to major urban interventions and transport developments. One Green Mile in Mumbai, and the Amazon Bus Station, Belém, Brazil.

The Future of Sustainable Architecture

Amazon HQ2 at Metropolitan Park by ZGF Architects, Arlington, Virginia | Popular Choice Winner, Sustainable Commercial Building, 12th Annual A+Awards

What technologies are being developed for the future of sustainable architecture?

BIM – Building Information Modeling is a powerful management framework that provides detailed insights into every aspect of a building’s construction and maintenance, boosting efficiency and cutting waste.

AI – Artificial intelligence is playing an increasingly big part in streamlining and fine-tuning building processes, ensuring the most efficient and effective solutions are deployed

Bio insulation – Insulation brings down energy use, and in doing so a building’s operational footprint. We need a lot more of it, but the materials involved are often damaging to the environment. Mycelium – the root-like structure of fungal communities – is one of many bio alternatives now available

3D printing – Accuracy counts for plenty in the sustainable age, and 3D printing is as accurate as it gets. Improving the impact again by maximising resources, it’s also possible to use recycled raw materials to produce whatever structure you’re printing, turning construction into a circular process involving pin point precision.

Energy production – In an ideal world, the future of buildings isn’t just carbon positive, it’s also energy positive. While hospitals, airports, and other key infrastructure sites have long had on-site energy production for obvious reasons, new projects are incorporating solar panels, wind turbines, and geothermal technology. The result means contributing to, rather than extracting from, over-stretched national grids.

Water conservation – Emissions, gases, carbon, and even biodiversity impact all get more air time than water, yet with population growth alone we’re running out of H20, and can’t survive without it. Rainwater harvesting, grey water recycling systems, and low-flow taps are just some examples of how architects are considering this often overlooked issue.

Architizer's 13th A+Awards features a suite of sustainability-focused categories recognizing designers that are building a greener industry — and a better future. Start your entry to receive global recognition for your work!

Top image: Interpretation Center of Biodiversity and Pile Dwellings in the Ljubljana Marsh Nature Park by Atelje Ostan Pavlin, Ljubljana, Slovenia | Popular Choice Winner, Sustainable Cultural Building, 12th Annual A+Awards

The post Architecture 101: What Is Sustainability in Architecture and Design? appeared first on Journal.