The Quiet Tensions of POPS: How Private Institutions Shape Public Urban Wellness and Access

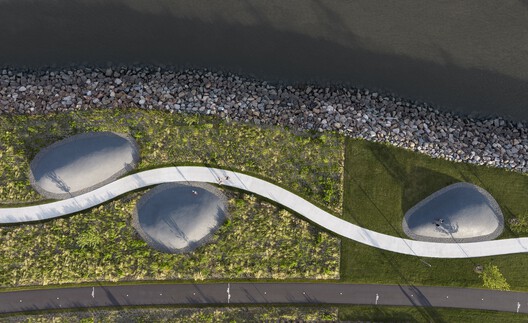

Sky Forest Scape / Shma Company Limited. Image © Phos Studio, Nawin Deangnul

Sky Forest Scape / Shma Company Limited. Image © Phos Studio, Nawin Deangnul

In contemporary urban development, the concept of Privately Owned Public Space (POPS) has gained increasing prominence. These are spaces that, while built, owned, and maintained by private developers, are legally required to remain publicly accessible. Often the result of negotiated planning incentives—such as zoning bonuses or increased floor area—POPS have become especially prevalent in dense urban environments where land is limited and demand for public amenities is high.

New York City remains the most thoroughly documented example, with over 500 such spaces—ranging from plazas to atriums—cataloged in Jerold Kayden's book, Privately Owned Public Space: The New York City Experience. Although originally conceived to supplement the city's public realm, POPS have long drawn criticism for favoring private interests over public benefit. Many of these spaces, critics argue, are carefully curated to serve developers and select their users, often falling short of their civic promise. Yet, despite their shortcomings, might there be ways in which POPS—when thoughtfully designed and equitably managed—can foster environments of wellness, reflection, and healing? Can they navigate the delicate balance between private gain and genuine public value?

In recent years, similar models have emerged across the globe, including in cities throughout Asia. In some cases, private developers may not directly own the public space, but are instead required—often as part of planning conditions tied to nearby developments—to design, build, or maintain public areas such as parks or plazas. These evolving arrangements prompt important questions: Can privately managed public spaces in Asian cities offer new perspectives on integrating accessibility, community engagement, and inclusivity? And how do local design approaches, governance structures, and cultural attitudes toward public space shape their outcomes?