MAD Architects at 20: From Beijing to the Global Stage

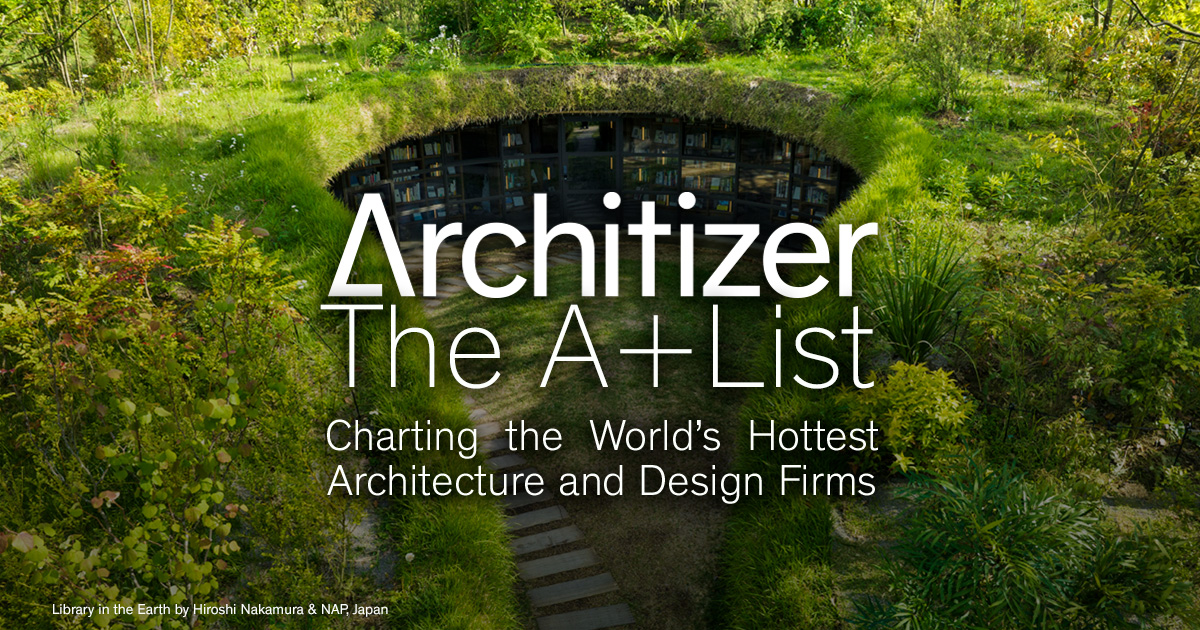

Call for entries: The 14th Architizer A+Awards celebrates architecture's new era of craft. Apply for publication online and in print by submitting your projects before the Final Entry Deadline on January 30th!

Over the past two decades, MAD Architects has built a body of work that resists easy classification. Their buildings are often described as futuristic or sculptural, yet those labels rarely capture what actually drives the practice. At its core, MAD’s architecture is concerned with how space is felt. How form, movement and landscape shape the emotional experience just as much as function.

Founded in 2004 by Ma Yansong, the studio emerged at a moment when contemporary Chinese architecture largely favored rational systems and restrained expression. MAD took the opposite position, treating nature, memory and intuition as design tools rather than indulgences. That stance initially set them apart, and over time, it solidified into a design language that is now instantly identifiable across continents.

As Ma Yansong joins the jury of the Architizer A+Awards, this timeline looks at the body of work that makes him one of the most compelling voices in contemporary architecture.

Learn More About Architizer’s A+Awards

Origins: Rejection of Rational Modernism

In the mid-2000s, as Beijing’s historic hutong neighborhoods were increasingly erased in favor of large-scale, standardized redevelopment, MAD Architects began testing a different approach. Rather than treating modernization as a choice between preservation and demolition, the studio explored whether change could occur through small, precise interventions that worked with existing urban life.

That position first materialized in Hutong Bubble 32, MAD’s first completed project and a built prototype of its Beijing 2050 vision, initially presented at the 2006 Venice Architecture Biennale and built in 2009. Inserted into a traditional courtyard compound, the mirrored “bubble” housed basic infrastructure while quietly activating new social use. Formally alien yet visually absorptive, it reflected brick, timber and vegetation, allowing the old and the new to coexist without clear hierarchy.

Hutong Bubble 218 by MAD Architects, Beijing, China | Photo by Tian Fangfang

A decade later, MAD returned to this idea with Hutong Bubble No. 218, expanding the experiment into a more complex courtyard renovation. The two projects frame the hutong as a long-term inquiry, establishing micro-scale intervention as a serious alternative to wholesale urban replacement. And in MAD’s case, a conceptual foundation for everything that followed.

Absolute Towers: The Project That Changed Everything

Absolute Towers by MAD Architects, Mississauga, Canada, Photo by Iwan Baan

Absolute Towers marked a decisive shift in MAD Architects’ trajectory. Won through an international competition in 2006 and completed in 2012, the twin residential towers in Mississauga became the studio’s first large-scale commission and its entry point into global architectural discourse.

Located in a rapidly developing North American suburb, the project challenged the prevailing logic of the residential high-rise as a neutral, efficiency-driven object. Rather than stacking identical floor plates, MAD designed the towers as continuously rotating forms, with each level subtly adjusted in response to orientation and view. A continuous balcony wraps the buildings, dissolving the rigid vertical segmentation typical of tall residential architecture and reconnecting domestic life with sky, light and landscape.

Nicknamed the “Marilyn Monroe Towers,” the project entered public imagination as much as professional debate. More importantly, it demonstrated that MAD’s approach (previously tested through smaller experiments) could withstand the demands of scale, engineering and regulation, establishing the practice as a serious international contender rather than a speculative outlier.

Cultural Landscapes: MAD’s Breakthrough in China

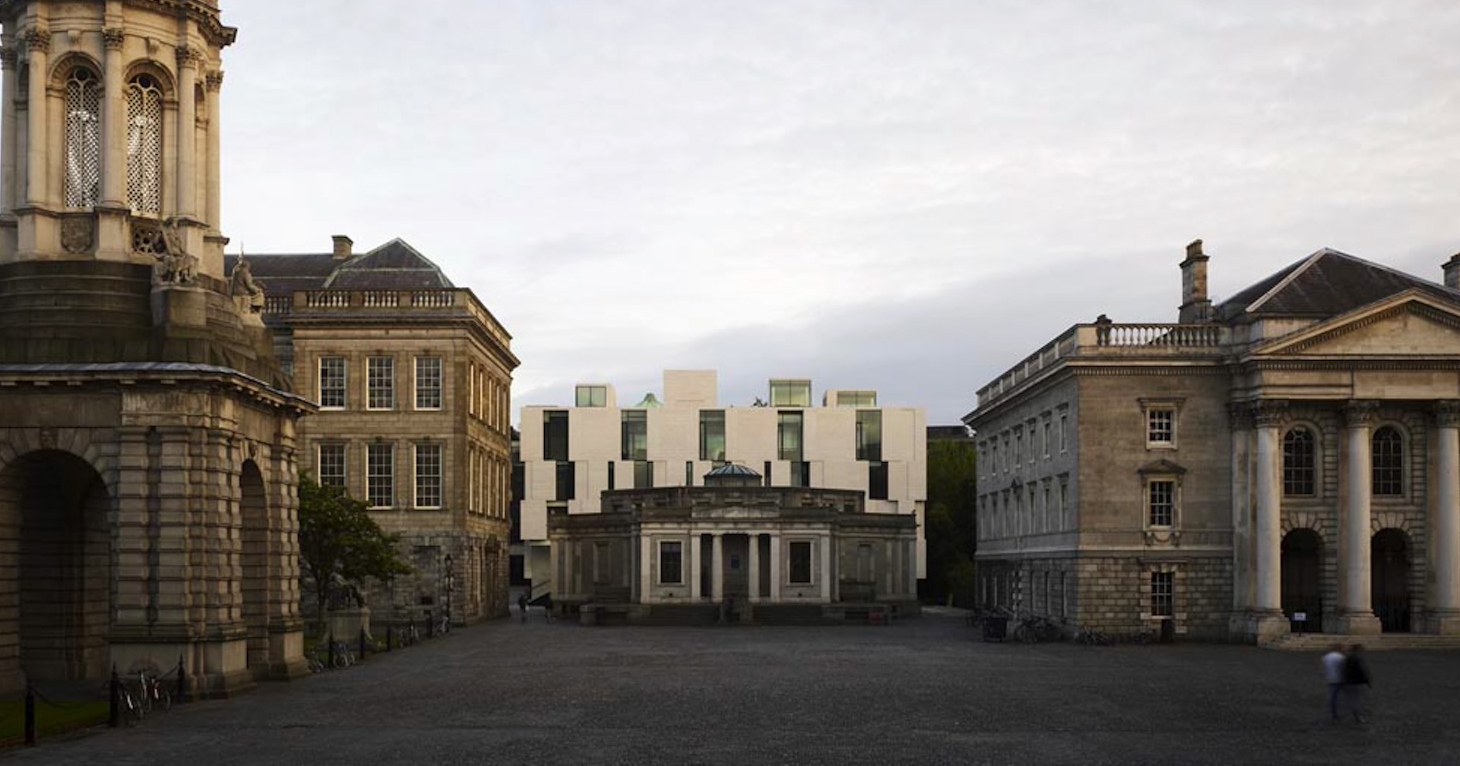

Ordos Art and City Museum by MAD Architects, Ordos, China

Ordos Art and City Museum by MAD Architects, Ordos, China

MAD’s first major cultural project in China, the Ordos Art and City Museum, reads almost like a refusal. Set within the rigid geometry of Ordos’ new city plan, the building appears as an amorphous mass that seems to have landed rather than been placed. Wrapped in polished metal louvers, it reflects and dissolves its surroundings, turning inward instead of engaging the city head-on. Inside, the logic shifts. Canyon-like corridors, skewed proportions and light filtering through skylights replace the clarity of the master plan outside. Culture here is not displayed as an object in the city, but protected from it.

That instinct carries through to the China Wood Sculpture Museum, where architecture again behaves as a continuous shell. The building feels compressed and geological, less concerned with visual openness than with framing cultural memory through sequence, mass and material presence.

Harbin Opera House by MAD Architects, Harbin, China | Photo by Adam Mørk | Popular Choice Winner, Architecture +Wood, 4th Architizer A+Awards

Harbin Opera House by MAD Architects, Harbin, China | Photo by Hufton+Crow Photography | Popular Choice Winner, Architecture +Wood, 4th Architizer A+Awards

This trajectory reaches its most confident expression in the Harbin Opera House. Embedded within wetlands and shaped by wind, snow and movement, the building no longer resists its context but grows from it. Visitors climb, cross and inhabit the architecture as if traversing terrain, blurring the line between performance space and public landscape. Here, MAD’s ideas fully open up. Architecture stops acting as an object and becomes an environment, signaling a shift from cultural protection toward collective experience.

From Cultural Expression to Public Responsibility

The “Train Station in the Forest” – Jiaxing Railway Station by MAD Architects, Nanhu District, Jiaxing, China

As MAD’s cultural projects gained visibility, the studio increasingly turned its attention to architecture that had to work not just symbolically, but operationally. These were buildings defined less by spectacle than by how they reorganized daily life in the city.

That shift is clearly articulated in the Jiaxing Train Station redevelopment. Rather than treating the station as a monumental object, MAD buried the transport infrastructure underground and returned the surface to the public as a continuous urban park. Trains, retail and circulation operate below, while above, citizens stroll, gather and pass through what feels like civic ground rather than transit space. The historic station is reconstructed at a one-to-one scale as a railway museum, anchoring memory within an otherwise contemporary system.

Yabuli Entrepreneurs’ Congress Center by MAD Architects, Shangzhi, Harbin, China | Jury Winner, Hall / Theater, 9th Architizer A+Awards

A similar sensitivity shapes the Yabuli Entrepreneurs’ Congress Center, where a national-scale institution is quietly embedded into a mountainous landscape. Its tent-like form resists dominance, favoring integration and atmosphere over assertion.

Quzhou Stadium by MAD Architects, Quzhou, China |Jury Winner, Stadium & Arena, 10th Architizer A+Awards

Quzhou Stadium by MAD Architects, Quzhou, China | Jury Winner, Stadium & Arena, 10th Architizer A+Awards

At the largest scale, Quzhou Stadium pushes this logic further. Submerged within a park-like terrain, the sports complex dissolves the boundary between elite competition and everyday public use. Here, architecture becomes infrastructure, landscape and civic space at once, marking a mature phase in MAD’s engagement with public responsibility.

MAD on the Global Stage

Fenix – the Tornado by MAD Architects and EGM architects, Rotterdam, Netherlands

By the mid-2010s, MAD’s trajectory had shifted from international recognition to sustained global practice. With offices established in Beijing, Rome and Los Angeles, the studio began operating across continents as a matter of course rather than exception. Projects in Europe, Japan and the United States followed not as declarations of arrival, but as natural extensions of a design approach already tested through cultural and civic work at home.

One River North by MAD Architects, Denver, Colorado

In Rotterdam, MAD’s Fenix opened in 2025 inside a former harbour warehouse, introducing a new public route that rises through the building and frames migration as a spatial experience shaped by movement and memory. In Denver, One River North carries related ideas into a residential context, carving a vertical passage through the building and allowing daily circulation to guide how the architecture is used and understood.

Lucas Museum of Narrative Arts by MAD Architects, Los Angeles, California

The same sensibility also shapes MAD’s expanding work in the United States, most notably in the Lucas Museum of Narrative Art, set to open in 2026 in Los Angeles. Organized as a continuous spatial sequence, the museum approaches storytelling as something experienced through movement, reinforcing the studio’s ongoing interest in how people navigate, inhabit and remember architectural space.

Looking Ahead: A Practice Defined by Continuity Across Scale

Courtyard Kindergarten by MAD Architects, Beijing, China | Photo by Iwan Baan | Popular Choice Winner, Kindergartens, 8th Architizer A+Awards

Across MAD’s work, scale has never been the point of departure. Whether designing environments for children, temporary installations for international exhibitions, or public spaces intended for slow, everyday use, the same principles recur. Architecture is approached as a lived sequence rather than a static form, shaped by movement, atmosphere and emotional response. The programs shift, the audiences change, but the underlying logic remains steady.

Con-stella-tion:Dunhuang by Atelier Alter Architects, curated by Ma Yansong (MAD), Venice, Italy

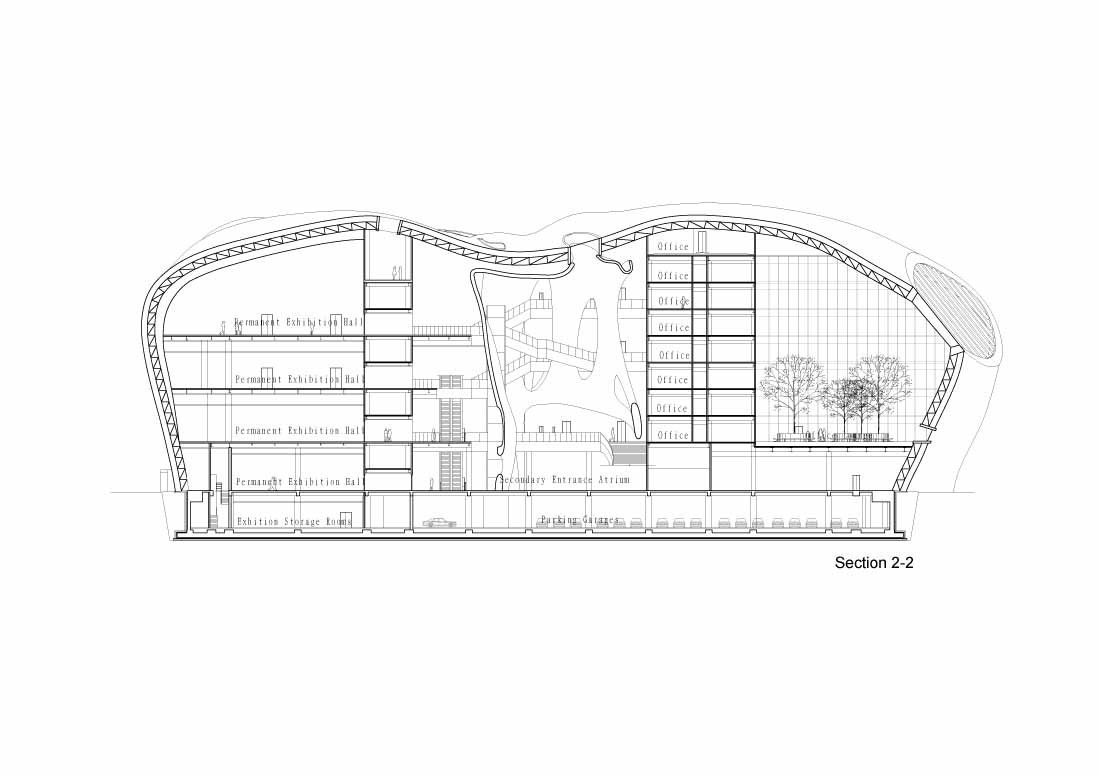

That same logic now informs MAD’s largest urban gestures, the latest of which is taking shape at Shenzhen Bay Culture Plaza. Planned as a major cultural and public complex along the waterfront, the project brings together exhibition halls, educational spaces and civic amenities beneath an expansive, earth-covered roof. Rather than asserting itself as an object on the skyline, the architecture folds into the landscape, extending the city’s public realm toward the bay and creating a continuous park that can be inhabited, crossed and occupied throughout the day. Circulation, topography and open space are treated as the primary architectural drivers, reinforcing MAD’s long-standing belief that civic buildings should first operate as places for people.

Shenzhen Bay Culture Park by MAD Architects, Shenzhen, China

As this work moves toward completion, Shenzhen Bay will also host the Architizer A+Awards Gala this January, situating the celebration within a setting that mirrors the values the awards seek to recognize. As Ma Yansong joins the A+Awards jury, his body of work offers a clear point of reference: architecture judged not by style or scale alone, but by its ability to remain coherent, humane and emotionally resonant across every context in which it operates.

Call for entries: The 14th Architizer A+Awards celebrates architecture's new era of craft. Apply for publication online and in print by submitting your projects before the Final Entry Deadline on January 30th!

The post MAD Architects at 20: From Beijing to the Global Stage appeared first on Journal.