"In post-disaster cities like Los Angeles, we need new model homes and we need them now"

After disasters like the Los Angeles wildfires one of the best ways for architects to help is by designing prototypes, write Dana Cuff, Emmanuel Proussaloglou and Ryan Conroy.

Octavia Butler's 1993 apocalypse novel, Parable of the Sower, is set 20 miles outside Los Angeles, where homelessness, environmental collapse, fires and poverty-induced violence have reached unlivable extremes.

Eerily, the book's first fires are set at the start of 2025, when it has re-emerged as a bestseller in Southern California following the deadly fires that swept across Los Angeles in January. Today's readers need hardly use their imagination if they ever drive through the devastation in Altadena, Pacific Palisades, or along Pacific Coast Highway.

Parable serves us architects searching for ways to recover in the wake of January 2025's fires

It is a cautionary tale about potential horrors on the horizon, as well as how individuals might survive to shape the future through the strength of community. The characters become refugees, reliant on survival skills, land and seeds to plant for harvest in the face of inescapable change.

Butler's Parable serves us architects searching for ways to recover in the wake of January 2025's fires.

Cynics say that the 800 architects at AIA Los Angeles' post-fire town hall were motivated by the prospect of all that new work after recent slowdowns in business. We see something different taking shape: architects, particularly from the burn areas, becoming civic leaders with an earnest desire to contribute in some way.

After Rodney King, we swept the streets of South LA and after Katrina, we designed and built houses for Lower Ninth Ward in New Orleans. But such help, if heartfelt, follows quickly on the heels of disaster and then withers as the spotlight moves elsewhere, without much thought or support for the people who will carry the work after the clean up over the following decades.

Los Angeles, at present, is buzzing with so many worthy efforts that redundancy, disarray and the potential for exploitation loom. Groups have formed to protect domestic workers who lost their places of employment and residents whose homes were uninsured. Burn-area survivors organize to defend against developers in Altadena and welcome them into Pacific Palisades, but no one is getting their neighborhood back.

At the civic level, the spectrum of leaders is mobilized – from the mayor to county supervisors and city councilmembers, universities to foundations, tech companies to church leaders. At some point, each turns to architects for help, since houses, churches, libraries, schools and businesses must be rebuilt.

With such an overwhelming recovery path ahead, architects as well as civic leaders tend to resort to big thinking

Our response thus far? Free services, standard plans, pro bono advice, material science information about fire hardening, and myriad essays, interviews, and op-eds about how the city should rebuild.

With such an overwhelming recovery path ahead, architects as well as civic leaders tend to resort to big thinking about masterplans, infrastructural solutions, and legislation. Intelligent post-disaster reports recommend widening streets to improve fire access, undergrounding electrical power or mandating new code requirements for fire-resilient building materials.

Inevitably, long-term, large-scale planning efforts meet outrage from those who seek speedy rebuilding for private property owners, and the entire process stalls.

What if the right solution at the start of recovery is neither comprehensive plans nor like-for-like rebuilding, but the germination of individual prototypes? Rather than talking about imposing our ideas, what if – like the characters in Butler's novel – we planted seeds?

In post-disaster cities like Los Angeles, we need arrays of new model homes and we need them now. The sooner we can plant them, the faster they will grow.

Inadvertently, the first seed was a survivor of the Palisades Fire. The photo of a single standing house went viral – a phoenix, a miracle, a model.

The Palisades seed models a more survivable future

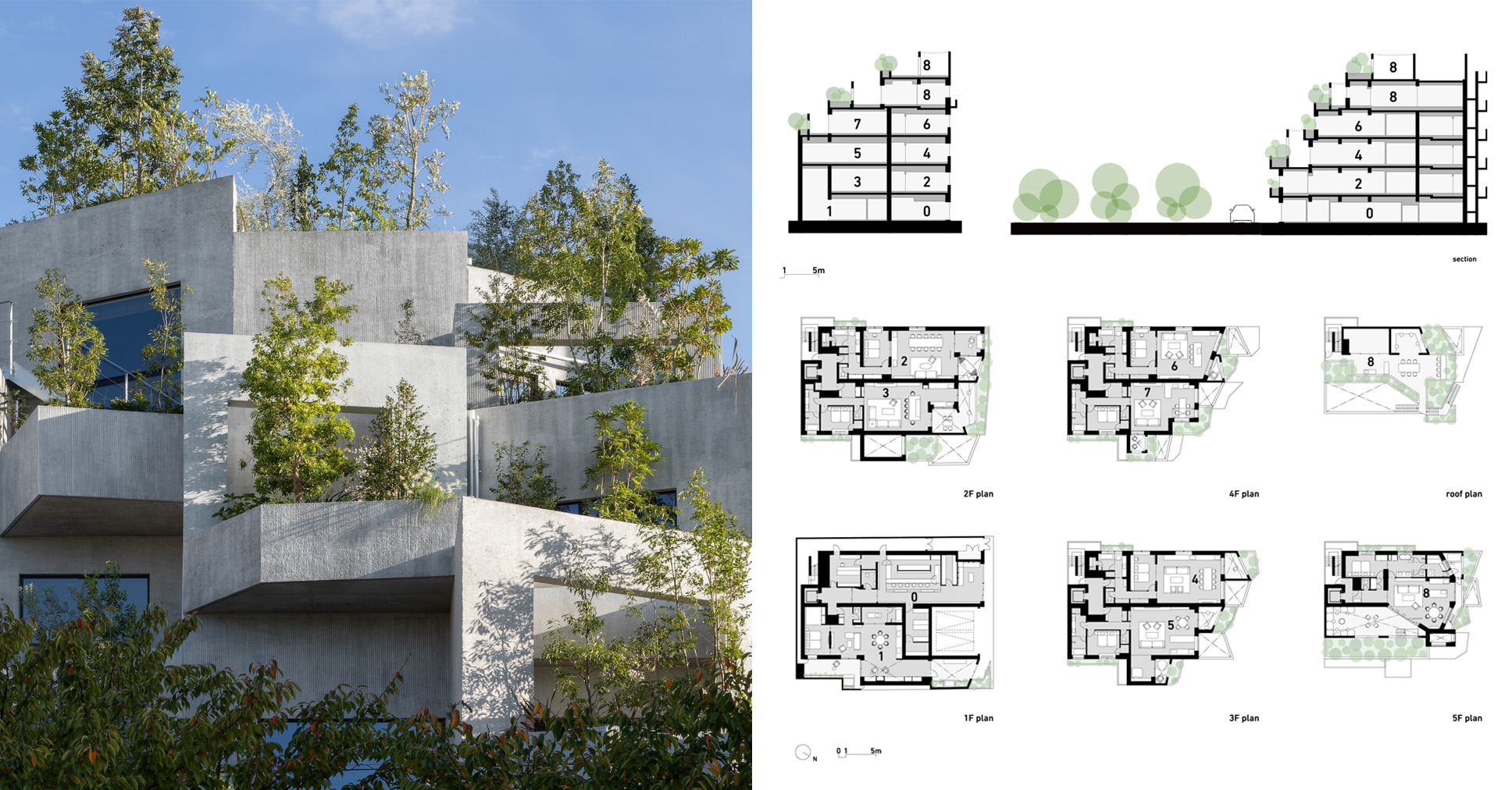

It was a discovery out of the ashes that architect Greg Chasen's design, built (mostly) to passive house standards, was a resilient structure, tightly sealed, without ornament or interior corners to trap embers, without eaves on its sloped metal roof, double-paned glazing, no nearby flammable vegetation, a low, concrete perimeter wall rather than a wooden picket fence.

The straightforward form was admired by neighbors who lost their homes, and crystallized proposed regulations that could drive rebuilding. Real-life demonstrations that people can see – and kick the tires of, as it were, spur opt-in pathways toward building back better, instead of the resistance met by abstract regulations.

Showing the way forward, the Palisades seed models a more survivable future. Chasen's home inadvertently became a full-scale model home – one powerful, tried-and-true means to forecast the future.

In Los Angeles, the opportunity to build new demonstrations is currently being offered by mayor Karen Bass in partnership with cityLAB-UCLA, our design research center, on city-owned land. Over 900 teams of students, architects and designers of all stripes registered for the Small Lots, Big Impacts competition to design resilient, compact starter-home schemes for sites smaller than a quarter-acre.

Winners, announced at the end of May, will be exhibited widely and linked to builder-developers aiming to construct those homes on about a dozen city-owned lots, breaking ground in summer 2026. This is warp-speed for those familiar with the excruciatingly slow building process; disaster rebuilding is even slower, especially when whole communities have been eviscerated.

In a separate effort with community partners, we are also working to plant on Los Angeles County sites a range of factory-built homes – modular, panelized, volumetric – to showcase greater efficiencies and speedier timelines for those impacted by the Eaton Fire.

We architects should be taking every opportunity to build full-scale, multi-faceted, publicly accessible demonstration houses

Given the pressing need and the slow pace of our industry, we architects should be taking every opportunity that arises to build full-scale, multi-faceted, publicly accessible demonstration houses, to overcome resistance to much-needed change.

Architects are stepping forward without waiting for a client to ask. We can create opportunities out of everyday work: the addition to your local school, the rector's residence, a mock-up on the community college campus, a prefab granny flat visible on a corner lot.

This open-source strategy is not the way we usually work. Creating models for the future means partnering with communities, assembling constituencies, gathering resources, harnessing media attention, and opening your practices so that others can follow.

In an interview, Butler says she wrote Parable about "a possible future… [by looking] at where we are now, what we are doing now, and to consider where some of our current behaviors and unattended problems might take us".

Her existential threats – global warming, water shortages, firestorms, houselessness, bankrupt governments – loom now, in the real 2025. Butler, as prescience would have it, went to school in Altadena.

In the face of forces beyond our individual control, we are wise to start working together in unconventional ways, collectively undertaking local, transformative actions that lay a path for others. It's not the only solution, it's not an easy solution, but it is one solution that can be planted and grown in your neighborhood garden – or city-owned lot.

Dana Cuff is the founding director of cityLAB and a professor of architecture and urban design at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). Emmanuel Proussaloglou is a co-director of cityLAB, leading on its Reimagining Housing research area. Ryan Conroy is associate director of architecture at cityLAB and an architect at Kevin Daly Architects.

The photo is by Greg Chasen.

Dezeen In Depth

If you enjoy reading Dezeen's interviews, opinions and features, subscribe to Dezeen In Depth. Sent on the last Friday of each month, this newsletter provides a single place to read about the design and architecture stories behind the headlines.

The post "In post-disaster cities like Los Angeles, we need new model homes and we need them now" appeared first on Dezeen.