"I wrote the first English book on art deco"

Bevis Hillier's 1968 book Art Deco of the 20s and 30s made art deco famous. As part of our Art Deco Centenary series, he reflects on the style's lasting legacy.

In 1968, when I was 28, I wrote the first English book on art deco. In the early 1960s, art nouveau was the rage, with three admirable books on the subject and major exhibitions of Aubrey Beardsley and the poster artist Alphonse Mucha at the Victoria & Albert Museum (V&A).

It did not need a soothsayer to realise that the next style due for popularity would be that of the 1920s and 30s – entre deux guerres, as TS Eliot called it.

I think the finest flowering was in American architecture

So you might think it was wily opportunism that caused me to write the deco book. It was a lot more. I have a theory that many people have a voyeurish interest in the period immediately before their birth – the period from which they were excluded. I, born in 1940 (the same year as John Lennon) looked back to the period my parents recalled as a golden age – the 20s and 30s, when there were no bombs, doodlebugs, tank traps and rationing.

You probably know that it was not called "art deco" in the 20s and 30s. It was called "jazz modern" or "moderne". The name art deco was derived from the great Paris Exposition des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels of 1925, of which the centenary is to be celebrated this year by a grand art deco congress in Paris.

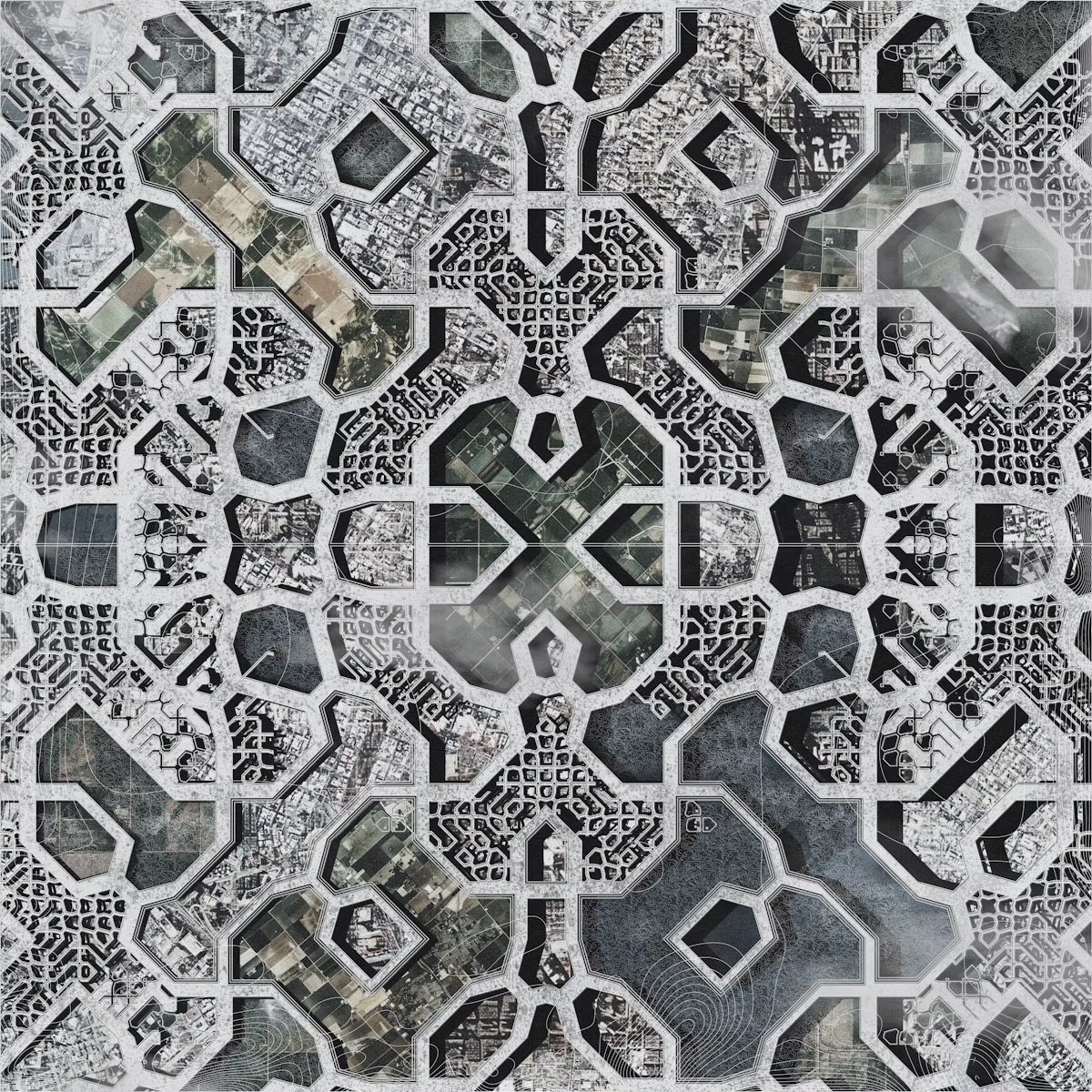

That will remind us that the origin of deco was in France; but I think the finest flowering was in American architecture – in New York, the Chrysler Building, the Chanin Building, the Empire State Building and Radio City Music Hall; in Los Angeles, the aerodynamic, streamlined Pan-Pacific Auditorium of 1935 (pictured top).

"Streamlined" is a word often applied to art deco. It is derived from mechanisation, making things sleeker in order to make them faster. A streamlined teapot might seem a rather ludicrous proposition – granny's teapot does not need to move faster – yet streamlined deco teapots there are.

It was all part of the way faster transport (cars, trains, planes) was affecting mainstream gallery art; also the fragmentation (only too literally achieved in the first world war) that certainly influenced cubism. My nutshell definition for art deco is "domesticated cubism".

In the five years 1984 to 1988 inclusive, I was a columnist on the Los Angeles Times. One of the first columns I wrote, in 84, was an attack on the City of LA for allowing its art deco buildings to fall into disrepair. What did they think tourists came to LA to see?

When I wrote my 1968 book, art deco was a despised style

I had a smarmy letter from a city officer assuring me that he cared deeply about the buildings. But the Pan-Pacific Auditorium became covered in graffiti, and the year after I left LA, it was burned down by an arsonist.

I am glad to say that Los Angeles now has a flourishing and proactive Art Deco Society, which has done wonders in restoring deco landmarks. Significant books on American deco, particularly architecture, notably Alastair Duncan's 1986 American Art Deco have alerted American culture-vultures to what they have – and what they have grievously lost, through a sort of aesthetic catalepsy.

That is all part of the international love of art deco, manifested in many more societies, in the several learned and less learned books that have been published on most aspects of deco; in high prices realised at auctions; and in the lauding of deco pieces brought on to television antiques and collecting shows. Pottery by Clarice Cliff (which I'm ashamed to say I omitted from my 1968 book) is a popular staple of those shows.

When I wrote my 1968 book, art deco was a despised style, rather as Victoriana had been in the 1950s. Since the 1980s, art deco has become a household expression.

With collectors and scholars, there are always bound to be disagreements. My other artworld love, besides art deco, has been English ceramics of the 18th century. There are constant arguments as to which factory made which pots, wares or figurines.

The study of deco has been riven by disagreements. For example, some people (notably, the writer and interior decorator Martin Battersby) have asserted that the 1920s and the 30s should be treated as quite separate subjects, the term "art deco" to be applied only to the 20s, and "modernist" to the 30s.

It affected everything from skyscrapers and luxury liners to powder compacts

I quite agree that the decades have different characters. In the 20s, as a reaction to the horrors of the first world war, there was an appetite for frivolity, having fun. They were the "roaring twenties".

In the 30s, which WH Auden called "a low, dishonest decade", with hunger marches and the rise of fascism in Germany, Italy and Spain, there was a more sharp-edged, austere style. The Wall Street crash of 1929 marks a caesura between the decades. But I have to point out that not all the artists and designers suddenly died off in 1930! There was a lot of continuity.

In 2003 the V&A held a large-scale exhibition of art deco. I was pleased that its organisers, in the exhibition catalogue, rehearsed the conflict over "art deco" and "modernist" and, quoting me, came down firmly on my side.

I encountered another kind of disagreement when co-organising with David Ryan, in 1971, a big exhibition of deco at the Minneapolis Institute of Arts. It was the happiest of collaborations; but at first we did not quite see eye to eye, as David wanted to show only examples of the highest quality – Puiforcat silver, Maurice Dufrêne furniture, Lalique glass – while I was intent on demonstrating that deco was, as I had called it in my 1968 book, "the last of the total styles".

It had affected everything, from skyscrapers and luxury liners to powder compacts, thermos flasks, lamp-posts and letter-boxes. We eventually agreed on a Hillier-slanted compromise. The luxury goods were shown alongside low-end market things – book jackets, ashtrays, even the downright kitsch of plastic candlesticks.

The Minneapolis show was particularly strong on costumes. I had managed to borrow from the Bath Museum of Costume some dazzling charleston dresses. I like to think that the singer Prince, who grew up in Minneapolis and was 13 in 1971, might have visited our show, and that the deco costumes might have inspired his extravagant get-ups.

Art deco burned so brightly between the 20s and 30s that its radiance survives

The fact that art deco was the last of the "total" styles is part of its continuing allure. No style since the 20s and 30s has so overwhelmingly affected everything – not even what is now called "mid-century modern" or "retro" furniture of the 1950s with cocktail-cherry bobbles on the legs, palette-shaped trays and varied frivolities. The relics of deco are all around us – cinemas, lamp posts, cafe doorways, a few hotel suites. Its force continues to challenge and beguile us.

Art deco burned so brightly between the 20s and 30s that its radiance survives, like that of a rock star struck down in his or her prime. Film directors love to show beaded dresses, shingled women's hair-dos, silver bangles, charlestons, and 20s skyscrapers. It is the most revived of all historic styles. The embers will just not fizzle out.

I am delighted that art deco is still in the ascendant. Long may it remain so.

Bevis Hillier is an art historian, journalist and critic. His 1968 book Art Deco of the 20s and 30s is credited with bringing the style into the public consciousness. As well as authoring several more books, he held editor roles at The Connoisseur magazine, The Times and the Los Angeles Times, and has also written reviews for The Spectator.

The photo is courtesy of Bevis Hillier.

Art Deco Centenary

This article is part of Dezeen's Art Deco Centenary series, which explores art deco architecture and design 100 years on from the "arts décoratifs" exposition in Paris that later gave the style its name.

The post "I wrote the first English book on art deco" appeared first on Dezeen.