Architects Ask: What Would a Post-Capitalist City Feel Like?

Call for entries: The 14th Architizer A+Awards celebrates architecture's new era of craft. For early bird pricing, submit by October 31st.

Cities are sprawling, rents are escalating, apartments flip hands faster than trading cards and glass towers rise like stock tiers. It’s true — in our contemporary cities today, every inch of space is expected to perform, to generate value and ultimately to sell itself. Private space is monetized more than ever before, while public space is a funnel leading us, through thoughtful advertising, to consumption.

Frankly, architects have lost their leverage when it comes to cities, giving way to real estate developers and investors to pave the way for house commodification to take hold. Although social housing has become a grave urgency for cities worldwide, it is only part of the solution to the wider reasoning behind city-making.

What if we pressed pause on profit-driven strategies and treated our streets, parks and buildings not as designs aimed to maximize return or investments but rather as spaces where care and community took center stage? In other words, what would a post-capitalist city look like?

Fred Hsu on en.wikipedia, NYC Downtown Manhattan Skyline seen from Paulus Hook 2019-12-20 IMG 7347 FRD (cropped), CC BY-SA 4.0

As ideal this idea may sound, it is not a concept that has never been materialized before. In medieval Europe, cities were formed through guild halls, communal pastures and marketplaces, where the residents shared both an active social life and the grind of production to survive. Labyrinthine-like streets opened up to small, public squares that acted as stages for trade as well as entertainment. Similarly, the Haudenosaunee Confederacy’s settlements in America were prioritizing the reciprocity between land and community, where longhouses were organized in relation to agricultural fields. This way, urban life was intertwined with collective survival and care rather than private ownership.

Finally, during the 19th century, as a response to the alienation spurred by the industrial revolution, a French philosopher named Charles Fourier imagined phalanstères — a utopian community, ideally consisting of 500 to 2,000 people, all working together for a mutual benefit. This community was essentially a building comprised of three distinct parts: the central one featured dining spaces, rooms for gatherings and libraries, the left wing was reserved for noisy activities such as carpentry and play and the other hosted merchants and travelers, who paid a fee for accommodation. The phalanstère also included private apartments and many social halls.

H. Fugère (artist) / Ch. Daubigny (engraver?), Houghton Soc 860.05 – Fugère, phalanstère, marked as public domain, more details on Wikimedia Commons

These precedents stand as examples of cities that aren’t bound to real estate goals or corporate branding and whose primary objective wasn’t profit but rather shared an ethic of communal living. Consequently, they can act as reminders for architects, proving that alternative urban models have always existed – it’s only a matter of recognizing their relevance in shaping more human-centric cities.

Let’s consider now the “ingredients” that make up cities. Private housing and retail, public space and lastly, infrastructure are potentially the three main categories that comprise an urban fabric. In a post-capitalist city, housing would no longer be viewed as an asset class.

Hagener Straße by Stefan Forster, Düsseldorf, Germany

Models such as cooperative housing open up possibilities both in terms of architectural as well as urban design. One example is the Hagener Straße project in Düsseldorf, Germany by Stefan Forster. Three beautiful, red-brick buildings house 188 cooperative-owned rental apartments as well as a children’s day nursery and communal facilities such as a laundry and tea house. In-between the buildings, a series of courtyards and ensemble corridors foster a deeper communication amongst the residents.

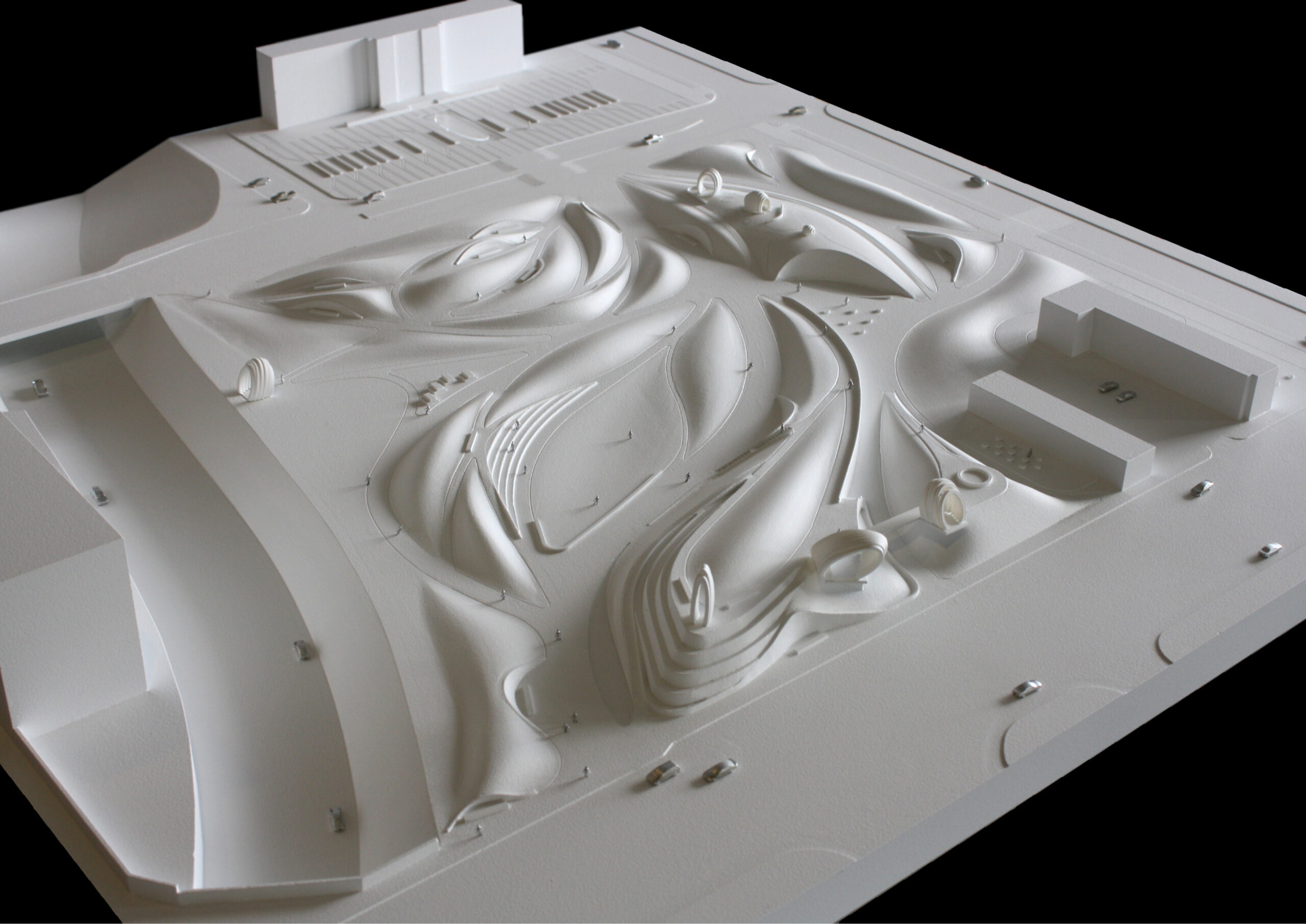

In parallel, by viewing public space as a place of “true commons” (i.e. resources of space that are collectively managed rather than a mere bridge between people and consumption) a city’s urban character would change dramatically. The Tongva Park and Ken Genser Square in Santa Monica, designed by Field Operations, not only introduces a new type of urban landscape-making but was also conceived through extensive public participation.

Tongva Park and Ken Genser Square by Field Operations, Santa Monica, California | July Winner, 2015, A+Awards, Public Park

What used to be an empty parking lot, is relinked with the rest of the city. The artificial topography organizes the site into four “thematic” areas: the garden hill, filled with vegetation, the discovery hill, a play-space for children, the observation hill, a framing of iconic views and, finally, a gathering hill, a large open space that flexibly houses all types of encounters.

Last but not least, infrastructure – the machinery of the city – could also shift from profit imperatives. Apart from providing universally accessible transportation, steering away from the private car and promoting a collective mobility strategy could be the key to a more balanced public space and convivial urban rhythms. The Bridge of Nine Terraces in Nanjing, China is a pedestrian bridge that spans over the Qixiang River.

Bridge of Nine Terraces by Scenic Architecture Office, Nanjing, China

What is striking about the specific infrastructure is its mixed-use design. Specifically, nine suspended platforms are connected by ramps and stairs, with a central passage for walking and side spaces for resting and hosting bridge-top markets, while also doubling for a boat passage. At the same time, a double-sloped roof, used to cover the shear walls, is used to design two additional “half-houses,” imbuing this pedestrian bridge with the warmth of a village homecoming.

Ultimately, the post-capitalist city is not a utopian vision. It is more about reclaiming architecture’s role in shaping spaces and, more widely cities, as well as rediscovering the life before profit became the priority.

Call for entries: The 14th Architizer A+Awards celebrates architecture's new era of craft. For early bird pricing, submit by October 31st.

Featured Image: Tongva Park and Ken Genser Square by Field Operations, Santa Monica, California | Jury Winner, 2015 Architizer A+Awards, Public Park

The post Architects Ask: What Would a Post-Capitalist City Feel Like? appeared first on Journal.