What will it take for us to eat lab-grown steak?

Lab-grown meat is gaining traction. But before we consume it, we need to believe in it – and that's where design comes in. Jane Englefield asks scientists, designers and a food critic what's at stake.

"What is meat, really?" considered emerging London-based food designer Leyu Li. "Is it defined by its molecular structure, its nutritional composition, its cultural role, its biological origin, or the emotional resonance it carries?"

Questions like Li's make lab-grown meat, which could be on sale in the UK within the next two years, an intriguing proposition.

"Far more sustainable" than conventional meat

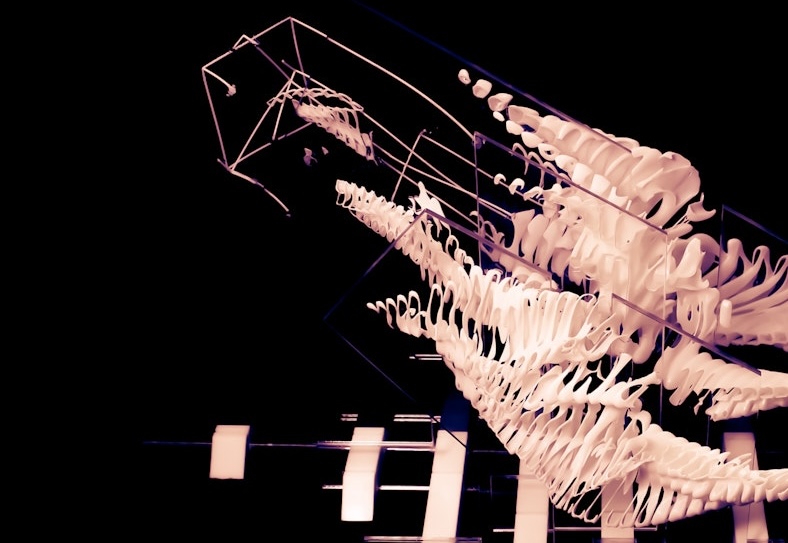

Also known as cultured meat, in vitro meat, clean meat and healthy meat – among other suggestive titles – lab-grown protein is produced in a bioreactor by cultivating cells that can be repeatedly extracted from a live animal without the need for slaughtering it.

Worldwide, lab-grown meat is still in its infancy. Singapore became the first country to green-light cultivated chicken for human consumption in 2020, followed by the United States in 2023.

The first slaughter-free steak was approved in Israel last year, while Australia permitted the use of cultured quail in June.

With conventional meat already accounting for around 60 per cent of the greenhouse gases caused by global food production and human population growth driving surging demand for protein, advocates of lab-grown meat describe it as more sustainable, healthier, and a game-changer for animal welfare.

American alternative proteins analyst Zak Weston is confident that cultivated meat is "likely to be far more sustainable" than animal-derived meat if scaled up.

"Even with early life-cycle assessments, we see significant land and water usage reductions along with reduced carbon dioxide emissions intensity, and it's highly likely that these metrics will improve as the technology matures and becomes more efficient," he told Dezeen.

But scaling up lab-grown meat for widespread consumption raises myriad practical and ethical questions, not least the creative challenges involved in making it look and taste palatable.

Recent revealing studies showed that just over 30 per cent of Americans find the concept of cultivated meat "appealing", while only a quarter of Britons would eat the protein if it were commercially available.

"As much a design challenge as a biological one"

Perhaps the trickiest task of all will be popularising the lab-grown beefsteak – an age-old cut of red meat that is infamously bad for the planet, but considered among the most desirable foods in many culinary traditions.

"Creating the 'perfect' steak, whether from plants or cultivated meat, is as much a design challenge as a biological one," explained Bianca Lê, a cell biologist at San Francisco lab-grown meat company Mission Barns.

"Texture, marbling, colour, and even how it cooks and sizzles – all these elements need to be intentionally crafted," she told Dezeen.

Mission Barns is one of three cultured-meat organisations currently approved for practice in the US.

All of the company's products are courtesy of resident "donor pig" Dawn, who Lê said "remains happy and alive in a climate sanctuary called Sweet Farm in upstate New York, while we're producing cultivated pork in San Francisco".

While Mission Barns is gearing up to serve its lab-grown bacon, pepperoni and meatballs at local restaurant Fiorella, Lê explained that designing structured whole cuts of cultivated steak is still some way off.

"Whole cuts of meat are made of muscle, fat and connective tissue," she said. "Producing and combining all three components at scale is costly and not yet feasible with today's technology."

Progress is being made on costs. Weston predicts that cultivated meat could reach commercially available cost parity with conventional meat within seven to 10 years, but he also acknowledged that "much more work remains to be done" in every area of scaling up the products.

Financial Times restaurant critic Jay Rayner agreed that it could be a while before lab-grown steak becomes the norm on our menus.

"My suspicion is that this isn't going to happen for a very long time," said Rayner, who once worked in an abattoir to confront his own carnivory.

"A steak is a very particular thing," he told Dezeen. "It's a lot of different things, and that's why I think it's proved to be so very, very difficult to replicate."

"Culturally, it can feel uncanny"

Naturally, our relationship with food stretches back further in the collective memory than almost anything else. But as recently as the turn of the millennium, lab-grown meat was merely an abstract idea.

The push for cultivated protein was popularised by American scientist Jason Matheny, who founded the cellular agriculture nonprofit New Harvest and in 2005 optimistically declared that "with a single cell, you could theoretically produce the world's annual meat supply".

This paved the way for Dutch pharmacologist Mark Post to create the first lab-grown beef burger in 2013, which reportedly cost £225,000 to produce.

Despite significant scientific progress since, the issue of consumer acceptance persists.

"The main cultural challenge, which is an interesting one, is a suspicion in certain quarters of what is regarded as something being unnatural," said Rayner.

"In an age when there is a backlash against ultra-high processed foods, making a market for something which is about as processed as it's possible to imagine may be tough," he added.

"Culturally, it can feel uncanny," offered Li. "It evokes concerns about artificiality, ethical ambiguity, and even bio-disgust."

This is especially evident in the US, where seven states have already banned lab-grown meat, including Mississippi.

"I don't know about you, but I want my steak to come from farm-raised beef, not a petri-dish from a lab," wrote the state's agriculture commissioner Andy Gipson last year.

Texas has also forbidden cultivated meat, with commissioner Sid Miller proclaiming that people "have a God-given right to know what's on their plate, and for millions of Texans, it better come from a pasture".

"If we look at the current state of world politics and the shifting right, and the lack of attention to climate change, while we might have assumed that the course of human history was leading us towards less meat consumption, I would say at the moment, all bets are off," observed Rayner.

"What we eat is political"

This might be where design comes in.

Caroline Cotto is a food researcher who understands the complexities attached to distributing appetising alternatives to animal meat.

Her California-based company Nectar conducts taste tests of protein alternatives as part of chef-prepared meals, complete with all the expected trimmings and condiments, in restaurant-style settings.

The idea is to orchestrate "a much more authentic experience for consumers than being served a quarter of a burger patty naked on a plate" in a laboratory.

For Cotto, a key challenge is demystifying the underlying motivations behind why people eat meat and resolving "what they would need to be true" to adapt their diets.

"What we eat is political. It's cultural," she acknowledged. "It's not easy for people to make the link between food and climate. And then it often requires them to sacrifice something or change their personal behaviours, which is a largely unpopular practice."

Designers like Li are also aiming to redirect perceptions. In 2023, she created three conceptual products that combine lab-grown meat with vegetables, playfully called Broccopork, Mushchicken and Peaf.

Part of Li's project involved promoting the products on TikTok to an audience who didn't know whether they were real or not, under the pseudonym account Meaty Aunties.

Li's goal was not to predict or dictate the future of meat, but to expand the way we think about it.

"The 'perfect' fake steak is not just a matter of mimicking marbling and texture," she explained. "It's about creating a believable story."

"Designers have a unique role in this space," added Li. "Not only to help translate scientific innovation into sensory experiences, but also to expand the vocabulary of what meat can be."

"Even if it's molecularly identical, we're sceptical," agreed London creative strategist and cultural researcher Liv Taylor. "Because our relationship from source to table through the centuries deeply influences how we perceive flavour."

Some suggest that hybrid products like Li's could be on our supermarket shelves and restaurant menus before more complicated whole cuts like steaks, not only as a solution to logistical obstacles but also as a way to introduce consumers to partially lab-grown meat products.

"It's going to take a while to get to fully cultivated products," acknowledged Cotto.

"But in the interim, what if we were to use real animal meat as sort of a flavouring mechanism, using animal fat, or just smaller amounts of animal meat, and combine that with plant-based ingredients?"

"There is a tendency in the food world to lecture"

Then there is the possibility that lab-grown meat will never really take off. Insect protein has been proposed as another potential meat alternative, perhaps as one of a number of ingredients in cheaper meat products, such as sausages or pre-made lasagnas.

Packed with health benefits, insects are already eaten diversely across Africa, Asia and South America, but are generally less familiar to western cuisines.

"There is no doubt that proteins from insects are exceedingly environmentally friendly," said Rayner.

"People say things like, 'will we be eating insects?' To which I say, no, we will not be eating bugs, because it's culturally not what we do," continued the food critic. "But somebody will come up with proprietary animal protein products, and they will be called something like Nature's Bounty, rather than Bugalicious."

"As long as some smart marketing is done, it could be acceptable on that level," he added.

"A lab-grown steak versus organically farmed insects," mused Taylor. "I'm intrigued as to which people would be more comfortable with."

Despite his speculations, Rayner also cautioned against not only attempting to predict too far into the future, but also policing global eating habits with a one-size-fits-all lens.

"There is a tendency in the food world to lecture those on low incomes about how they feed themselves in a very paternalistic, patronising sort of way, without recognising the challenges of real poverty," he warned.

"Many things become very expensive, and for those who are looking to feed themselves and their families on very low incomes, this whole debate is completely irrelevant."

Dezeen In Depth

If you enjoy reading Dezeen's interviews, opinions and features, subscribe to Dezeen In Depth. Sent on the last Friday of each month, this newsletter provides a single place to read about the design and architecture stories behind the headlines.

The post What will it take for us to eat lab-grown steak? appeared first on Dezeen.