"The Brutalist somehow manages to get the architecture all wrong"

The Brutalist won a trio of Oscars last night, but it failed to say anything meaningful about architecture, writes Edwin Heathcote.

The Brutalist tries hard to be an epic movie. And how often do we get an epic about an architect? Pretty much never. But it is not, I'm afraid, an epic movie about architecture.

Despite what is a beautifully acted, directed and shot film, it somehow manages to get the architecture all wrong. You'll know the story by now; Hungarian-Jewish, Bauhaus-trained architect László Tóth (Adrien Brody playing Adrien Brody doing serious cinema) survives the Holocaust and arrives in the US.

Even the severest of brutalists wouldn't have conceived a building as grim as this

He struggles to find work until he is commissioned by a tycoon's son to build his dad a library as a birthday surprise. In the father, Harrison Lee van Buren (played by Guy Pearce), he finds his patron and he goes on, after an inevitable struggle, to great things. Though what we see is the struggle, the great things are less clear.

Architecture is used here as a cipher for so many things; it represents creative genius; it represents the opposition between radical Europe and the capitalist US; it represents civilisation through culture against the barbarity of the Holocaust (and, perhaps, US capitalism); it represents difference and alienness.

It represents the visionary and the individual, yet also, somehow it is about the building of a community centre. It represents the ecstasy and the tragedy of heroin addiction. It represents darkness and light, shadow and void, the many parallels of cinema and architecture. And so on. And on.

In fact it represents far too much and the architecture struggles to bear the weight of this burden. And the reason it struggles so hard is because the architecture is rubbish.

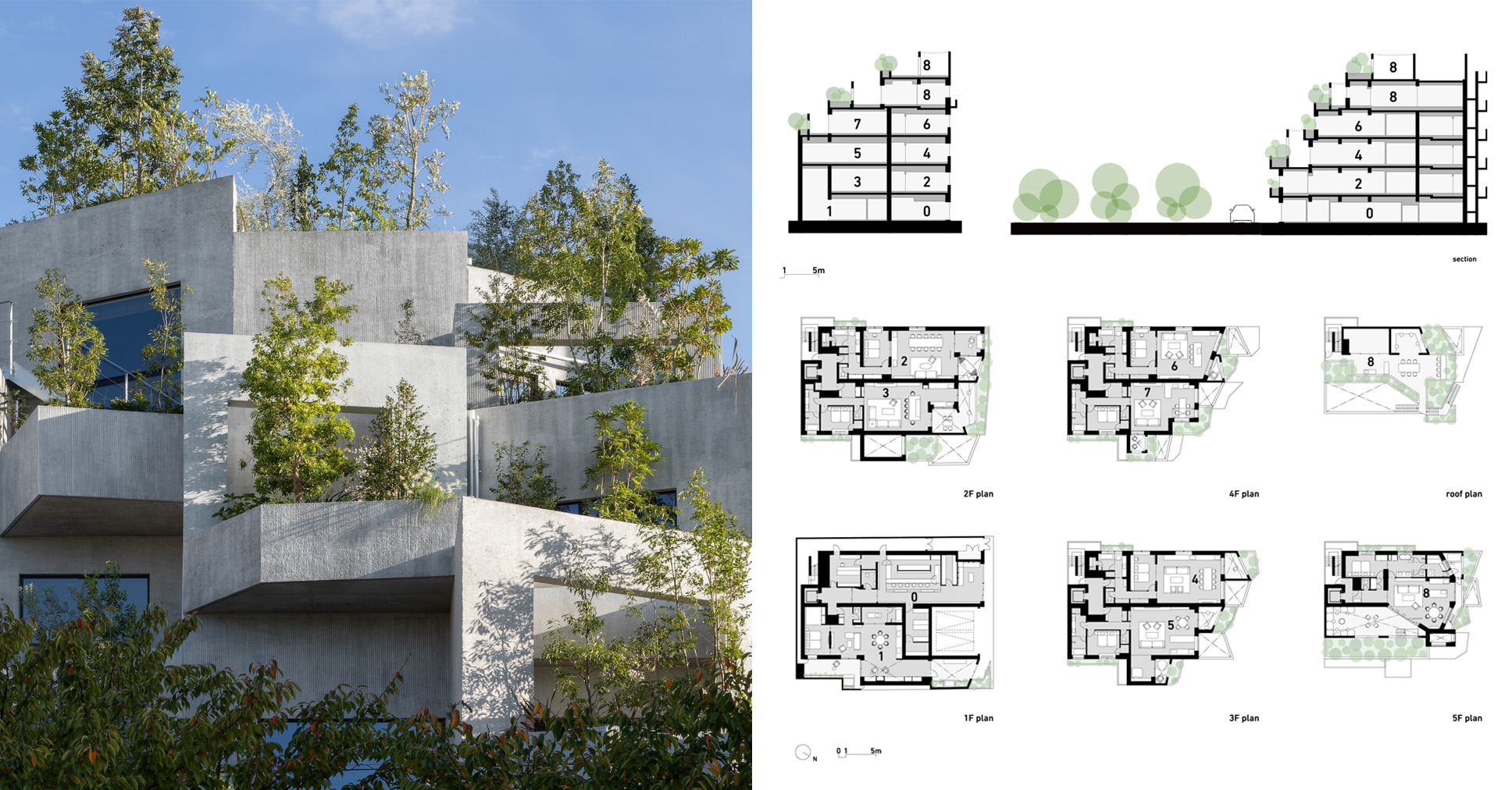

At the centre of this tale is this dark volume atop an American hill (for added piquancy the movie was wholly shot in Hungary). This odd chapel-cum-community centre has been commissioned by Van Buren and it remains a construction site for all the time we see it. It is, we are supposed to understand, a brutalist building (hence the title). It is not.

The building we see taking form (and in the shape of a huge model being lifted in to a presentation) is weird. A concrete volume with a pair of towers which together create a crucifix in the void between them and windowless walls – even the severest of brutalists wouldn't have conceived a building as grim as this. In parts it seems to owe a bit to Louis Kahn (legit), in others a little more Tadao Ando (anachronistic) and perhaps elsewhere it looks a little late Soviet (odd).

Surely the production designers could have turned to the work of real emigre Hungarians

Surely the production designers could have turned to the work of real emigre Hungarians, Marcel Breuer (whose wonderful building for the Whitney Museum in New York is currently being redesigned for Sotheby's by Herzog & de Meuron) or Ernő Goldfinger in London (whose Trellick and Balfron Towers better exemplify the social concerns of the era's architects).

The building here, perched on its hill and seen so often in silhouette, half-Golgotha, half-dance-of-death in Bergman's Seventh Seal, emerges not as a coherent volume like the model but rather as a series of submerged, cavernous spaces; dark, flooded and sinister. It is Tarkovsky's Stalker seen through the lens of Instagram.

The rationale for the proportions emerges from a storyline twist and becomes the destination of another. Neither make any real sense. These twists, for which the whole movie has been a set up, attempt to use the architecture but neither show nor tell.

Paradoxically director Brady Corbet has been meticulous in his reconstruction of the era, even down to the Vistavision in which the movie is filmed, a film format which gives it that authentic 1950s grain, a particular, lush palette and scale of Douglas Sirk or Hitchcock.

Everything from the costumes and the cars to the skylines and the soundtrack have been recreated with breathtaking care and attention to detail. My ear was particularly seduced by Brody's fine Hungarian accent and his and his wife Erzsébet's (Felicity Jones) outstanding spoken Hungarian (through a twist of fate, I should explain, I speak Hungarian).

Usually the movies don't bother with good Hungarian, it is a generic baddie language, a bit Bela Lugosi, a bit Usual Suspects, a good language to use when you want something no-one, or almost no-one will understand. But here it is done to perfection. And then I read something interesting; the speaking of this notoriously difficult language was helped along by artificial intelligence (AI), a little post-production nudge.

Tóth's buildings are a weird cocktail of late-modernist banality and late-postmodernist whimsy

AI? In Vistavision? Oh yes. In fact it turns out that AI was employed to help the architecture along too. And that explains a lot. It explains, I think, why the building is so bad. But more than that, it begins to explain the end.

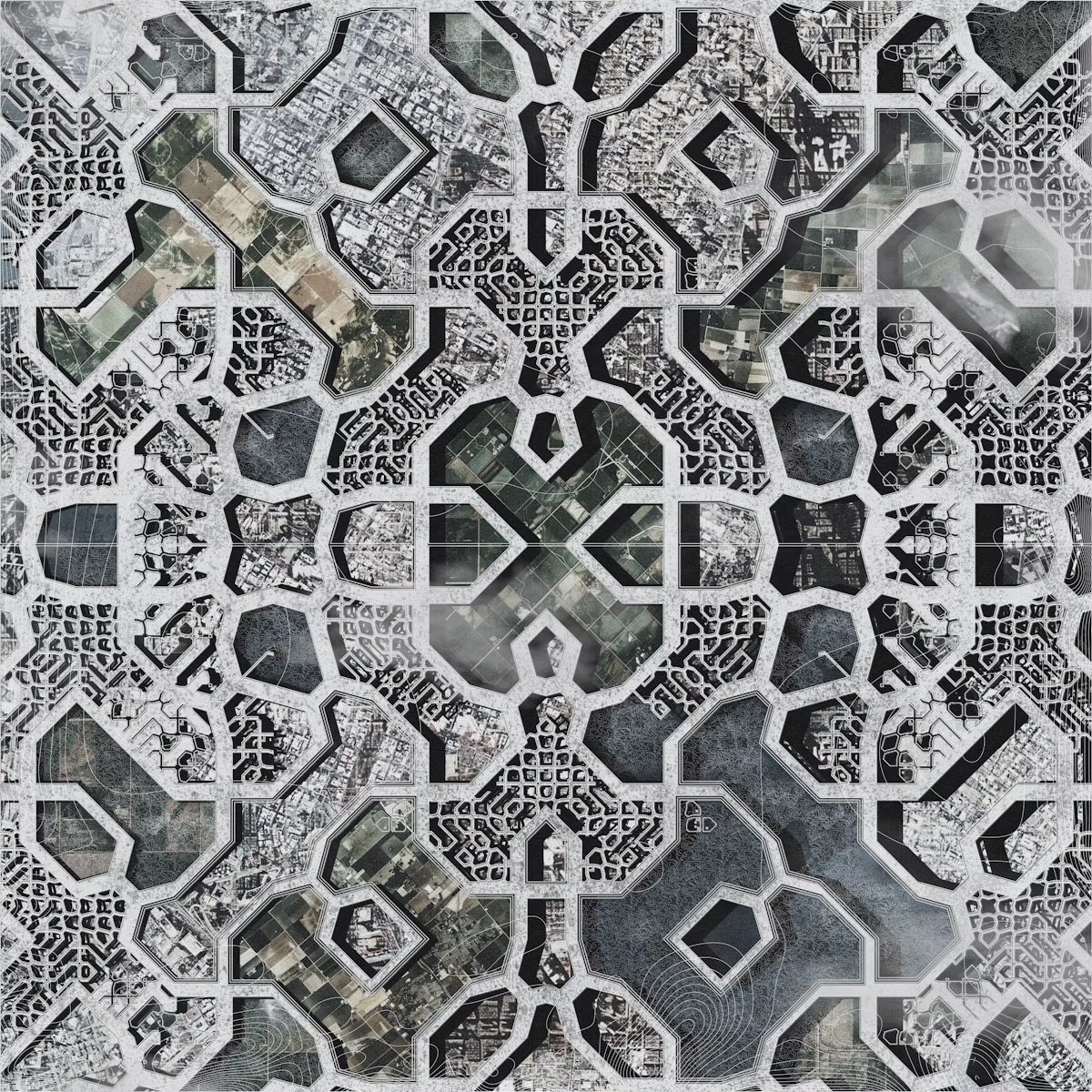

I don't think it's a spoiler to say that Tóth is finally recognised for his work. We see him being wheeled into an opening, the opening, it turns out, of an exhibition of his work at the inaugural Venice Architecture Biennale in 1980.

This, you might think, is a little curious. The theme of that biennale was "The Presence of the Past", which the movie trumpets out loud. It was the moment postmodernism broke out into the open, hit the mainstream in a flurry of columns and split pediments.

There's a fundamental misunderstanding here. That biennale was about the revival of history and representation, about the waning of modernism and the rise of references, of irony, humour, kitsch. We see some of Tóth's buildings and they are a weird cocktail of late-modernist banality and late-postmodernist whimsy. They are nothing like brutalism at all.

It turns out that AI was used here too, to create a back catalogue, to save time for the production designers. Yet this is the climax, the moment we see what Tóth has bequeathed the world and most of it looks like, well, a multi-story parking garage for an early 1990s Minnesota mall. It is dire. Architectural Intelligence this is not.

I suggest that the confusion is generational. In 1980 The Presence of the Past meant living once again among the ruins, it was about history re-emerging after having being suppressed by an excessively ideological modernism that denied the past. In 2025 "the past" means something else; it has become personal. It is all about trauma, embodied tragedy and epigenetic lingering suffering.

The Brutalist represented an opportunity to really say something about architecture

I am about to introduce an enormous spoiler here so please stop reading if you think you might be surprised by the twist; Tóth's masterpiece is based on the proportions of the concentration camp in which he was a prisoner. He is imposing an architecture of horror on an innocent community.

There are plenty of other things wrong here too. First is the suggestion that Tóth is somehow all alone in America; the US was teeming with Bauhaus refugees and modernist transplants from all across central Europe; Breuer but also Gropius, Mies, Moholy-Nagy alongside earlier emigres, Richard Neutra, Rudolph Schindler and dozens of ceramicists, artists and film-makers. He would not have been alone or unrecognised but part of a strong intellectual community.

And then there is the dialogue. "I find our conversations intellectually stimulating," Van Buren says, twice, to Tóth. Yet neither man says anything remotely interesting or profound in any of their conversations. The best dialogue is given to Tóth's long-suffering wife Erzsebet, nicely played by Felicity Jones. Like the architecture itself, the conversation is cliched nonsense.

Architecture is appearing as a character increasingly often in film and on TV, from the eye-wateringly terrible Megalopolis to the use of Eero Saarinen's coolly brilliant Bell Labs in Severance. More than three-quarters of a century after the entertainingly dire The Fountainhead, The Brutalist represented an opportunity to really say something about architecture. It fluffed it.

Edwin Heathcote is an architect and writer who has been architecture and design critic of the Financial Times since 1999. His numerous books on architecture include Monument Builders, Contemporary Church Architecture and the recently released On the Street: In-Between Architecture.

The image is courtesy of Universal Pictures.

Dezeen In Depth

If you enjoy reading Dezeen's interviews, opinions and features, subscribe to Dezeen In Depth. Sent on the last Friday of each month, this newsletter provides a single place to read about the design and architecture stories behind the headlines.

The post "The Brutalist somehow manages to get the architecture all wrong" appeared first on Dezeen.