"I'm teaching students not to follow Mies van der Rohe's example"

Architecture students are often taught about Mies van der Rohe as a master of modernism but they should also learn about the problematic legacy of some of his most significant work, writes Leen Katrib.

I first heard of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe as an undergraduate in the early 2010s. Mies was one of the most influential modern architects; I saw him as a disciplinary anchor – someone whose work helped me situate the contemporary architects I would later work for and follow.

That's why I added his works to the map of my own architectural pilgrimage: New York's Seagram Building; the Barcelona Pavilion; Farnsworth House in Plano, Illinois; and Crown Hall, home to Illinois Institute of Technology's (IIT) College of Architecture in Chicago, which Mies led from 1939 to 1958.

I've been leading the charge on a critical revision of Mies van der Rohe's racial legacy in America

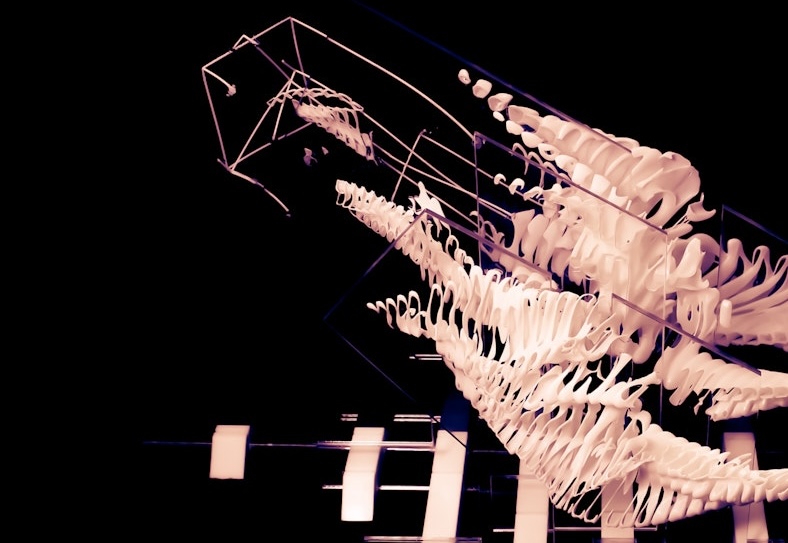

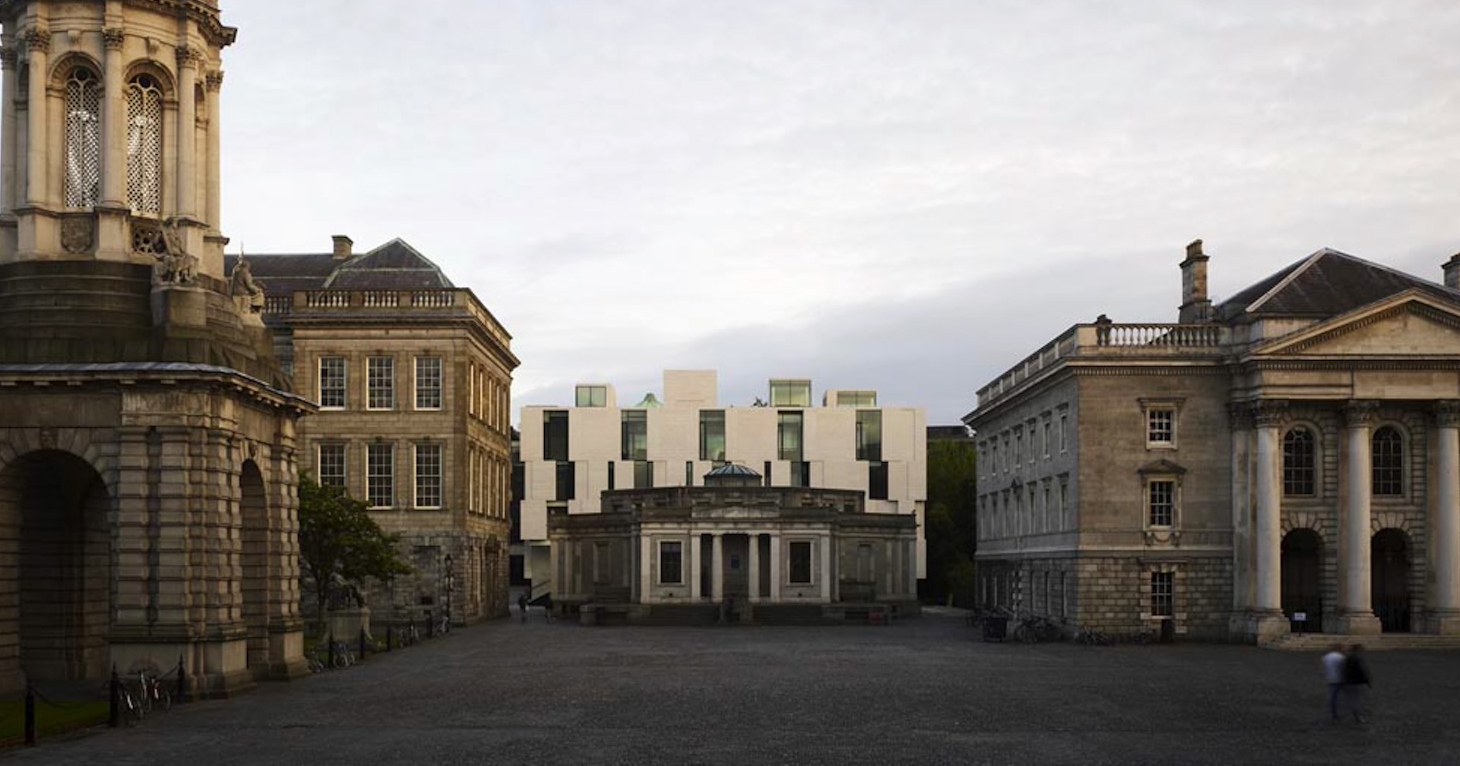

At IIT, Mies was given a rare opportunity and a bigger responsibility than most architects could ever dream of: to design a new campus masterplan, all its institutional buildings, and a new architectural curriculum. The campus became one of the world's largest collections of his buildings.

A few years ago, while I was designing a university building myself, I came across a report of objects recovered during a tunnel repair near Crown Hall. They belonged to Mecca Flats, a hotel-turned-residence built in 1892 that was significant during Chicago's Black Renaissance. The building's generously lit glass-roof atrium and the vibrancy of its publicly accessible open courtyards set the stage for an active communal life that inspired The Mecca Flat Blues by jazz composer Jimmy Blythe and In the Mecca by the poet Gwendolyn Brooks.

Despite a decade of fierce resistance the tenants were evicted, and in 1952 Mecca Flats was demolished to make way for Crown Hall. In fact, vast swaths of Chicago's Bronzeville neighborhood were leveled as part of the larger urban renewal project that would make way for IIT's campus expansion, designed by Mies van der Rohe.

While this backstory was known to architectural and cultural historians, and of course, Bronzeville's Black community, it was unknown to many – including me as a student who was taught to revere Mies's contributions strictly through terms of rigorous order, proportion, structural clarity and material honesty. How could this racial underside to one of the most celebrated works of modern architecture go consistently unmentioned – to future architects, planners and builders, no less?

I am now a professor of architecture. Uncovering the racial impact of higher education's ever-expanding built environment – and the architects, planners and builders behind these projects – has become central to my teaching. I've been leading the charge on a critical revision of Mies van der Rohe's racial legacy in America, which I've spent the past three years developing and presenting nationally and internationally. I've installed traveling exhibitions at several institutions to bring this history to both architectural and lay audiences, deconstructing the tools and methods that went into elevating the narratives of architectural genius while ignoring the displaced people and histories.

Mies was famously indifferent about race

It's deeply problematic that I only learned the full story behind Mies' IIT campus through a chance encounter with a news article about an archaeological find. By framing the campus solely through Mies' mastery of proportion and detail, we are failing to explain modernism's enduring influence on racial geographies across the American landscape.. That's why I'm teaching students not to follow his example.

To be sure, other campus designs have bulldozed communities: University of Pennsylvania, Columbia University's Manhattanville campus, Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis and University of Southern California, to name a few. None, however, is as strongly linked to its architect as Mies is to IIT, which defined campus planning by being one of the country's first federally funded post-war urban renewal campus expansions.

There is no evidence suggesting that Mies was racist, nor is that a conclusion I'm drawing by calling for a revision to his legacy. In fact, the few Black students who attended IIT in the 1940s and '50s reported a supportive environment that treated them on par with White classmates.

Mies, rather, was famously indifferent about race – not an uncommon position amongst architects of his time. He represents a broader ideology that cast architecture as a politically neutral act of creative expression and ushered in a lineage of designers and builders who propagated this belief.

In a famous photomontage he produced in 1941, he simply superimposes a photograph of a physical model of the proposed campus onto an aerial photograph of Bronzeville. The campus sits on a raised white plinth in defiance of its place in Chicago's Black Belt.

In many of his other architectural representations of campus buildings, context is similarly absent. And in class, when he asked his students to design a new university campus, they generated proposals that similarly shied away from representing or integrating existing context.

It's our responsibility to acknowledge the racial underside of architecture

Biographers of Mies have either ignored the impact his work had on the lives of Black communities or rationalized his indifference as a general detachment from the human condition. Such neutral reading was partly shaped by what Mies himself wrote in 1924, declaring that "questions of a general nature are of central interest. The individual becomes less and less important; his fate no longer interests us".

Mies's legacy, however, is inextricably entangled with the racialized restructuring of American cities. Beyond Chicago, his Lafayette Park residential campus in Detroit stands on the bulldozed traces of the Black Bottom community.

And I recently received a Graham Foundation grant to investigate a similarly problematic campus expansion master plan at Auraria Campus in Denver, which will mark its 50th anniversary next year. That is, 50 years since more than 300 Chicano families were evicted and their community demolished to expand a campus and unite three higher education institutions near downtown Denver. The designers were former disciples of Mies.

Revising a legacy doesn't come easily, and the list of Mies apologists is long. But if we train future architects to focus solely on the design of buildings without pausing to critically assess their long-term impact on existing communities, we risk perpetuating a built environment that reinforces systemic inequities.

Such re-examinings are more crucial than ever in light of the Trump administration's threats against efforts to reconsider American history through the lens of race. As an educator responsible for shaping future architects, I remind my students that it's our responsibility to acknowledge the racial underside of architecture and to advocate for acts of redress for impacted communities.

Architects should see the welfare, safety and success of community members as part of their mission

Colorado's House Bill 22-1393, which perpetually extends the "Displaced Aurarian Scholarship" to descendants of displaced Chicano families, is a concrete example of institutional restitution, as is an NEH-funded effort by CU Denver faculty to examine Auraria's history. Illinois and IIT would do well to consider something similar for displaced residents of Bronzeville and their descendants.

The legacy of campus expansion does not end in an isolated episode of displacement but is a continuing cycle of harm. As architects continue accepting university commissions, professional organizations such as the American Institute of Architects (AIA), must call on their members to reject those that do not integrate community members into the design in a responsible way.

The next generation of architects should see the welfare, safety and success of community members as part of their mission. That would be a legacy to be proud of.

Leen Katrib is an assistant professor of architecture at the University of Kentucky, a PD Soros Fellow and a Public Voices Fellow of The OpEd Project.

The photo is by Arturo Duarte Jr.

Dezeen In Depth

If you enjoy reading Dezeen's interviews, opinions and features, subscribe to Dezeen In Depth. Sent on the last Friday of each month, this newsletter provides a single place to read about the design and architecture stories behind the headlines.

The post "I'm teaching students not to follow Mies van der Rohe's example" appeared first on Dezeen.