How Norman Foster became the most successful architect in history

Ahead of Norman Foster's 90th birthday this weekend, Dezeen explores how he became the most successful architect the world has ever seen – including by asking the man himself.

"It's just amazing what Norm has achieved in his career," Ken Shuttleworth, founder of Make Architects and a partner in Foster's firm for nearly 30 years, told Dezeen.

"I don't think any other architect has done what he's done," Shuttleworth continued. "He hasn't waned in any way as he's got older – in a way he's got better. He's a one-off."

No plans to retire at 90

Architecture historian Owen Hopkins compares Foster to tech titans Bill Gates and Steve Jobs.

"He is the one architect who occupies that position – in terms of wealth, influence, connection to politicians," he said.

"He's someone who has that ability to take technology, broadly speaking, and apply it to the everyday world in really profound and popular ways."

"In the history of architecture, Norman has produced the greatest number of architecturally important public projects," added Carl Abbott, a masters classmate of Foster's at Yale more than six decades ago.

Foster has won every major architecture award, including the gold medals of the British, American and French architecture professions, and the Pritzker Architecture Prize.

He was knighted by the Queen in 1990, later elevated to a lord, and reportedly still meets regularly with the King.

These honours reflect an unrivalled back catalogue of buildings. Highlights include the HSBC Building in Hong Kong – which Owen Hopkins dubbed "era defining" – the renovation of the German Reichstag, the Great Court at the British Museum and the Millau Viaduct in France, not to mention three Stirling Prize winners.

Along the way, Foster is widely believed to have become by far the world's richest architect via his international firm, Foster + Partners, with a net worth running into the hundreds of millions.

He now spends part of every year at an estate he owns in Massachusetts that was formerly the Obamas' holiday home.

All this has been achieved despite coming from famously humble beginnings in Manchester.

Foster was bullied at school and left at 16. He later worked variously as a baker, bouncer and ice-cream-van driver to fund his initial architecture studies.

He has also experienced hardship later in life, suffering the untimely bereavement of his first wife, Wendy, in 1989 and nearly dying of cancer and suffering a heart attack in the early 2000s.

But despite approaching nonagenarian status, Foster has remained incredibly fit, regularly undertaking ski and cycle marathons.

He also has no plans to retire. "I continue to act strategically as the chairman and also to have a very personal role in a selected number of projects with a broader overview of the others," he told Dezeen.

"I travel extensively, am immersed in design, sketch and draw non-stop, and spend time with graduate students in the masters course and workshops run by the Norman Foster Foundation and its institute."

"I don't think even he predicted this"

This remarkable journey – from working-class kid with a slight lisp to trendy avant-garde architect to leader of a business empire – has cast Foster as an enduring source of fascination for the media.

As long ago as 1999, the Guardian declared that "there has never been an architect like Foster". Earlier this year, he was the subject of an 18,000-word profile in The New Yorker.

Nevertheless, at Yale in the early 1960s, it was not obvious to Abbott that such greatness lay ahead for Foster, who was invited to the university on a full scholarship.

"I did not expect Norman to reach these heights," he said. "I don't think even he predicted this."

"No, I didn't think that would happen," echoed fellow classmate Su Rogers, who is also the only other surviving partner of Foster's first studio, Team 4.

"There was a sense that he was very keen to earn enough money to live in a nice, elegant flat, but we all had that kind of ambition," she told Dezeen.

"I could see he was driven, but I didn't really think about him becoming a millionaire or anything like that."

Even so, Foster's rare ability to assemble and run a team was already becoming apparent, as fellow students volunteered to assist him on projects.

As well as Foster's well-documented closeness with Richard Rogers, Abbott also believes that Yale's school of architecture head at this time, Paul Rudolph, was a major influence.

Rudolph ran the class with militaristic severity, with students subjected to excoriating feedback in design juries.

"It was so intense," recalled Su Rogers. "Rudolph was very tough."

"Rudolph never stopped," said Abbott. "He was intense, always searching for the very best."

Foster is known to have a similar drive for perfection in his own approach to designing and to working in general.

"There's no resting on your laurels," said Shuttleworth. "There's always that constant search to find the right solution to a project."

"I mean, he's just always moving forward. It's relentless, there's no let-up – he just keeps going."

Patty Hopkins, a high-tech contemporary of Foster's whose late husband, Michael Hopkins, partnered with him in the early 1970s, recalls an episode from that period that demonstrates Foster's steeliness.

"I remember an early meeting in the Foster Associates office that I was at," she said. "It was with a journalist who came to write about a new project."

"It was very early days, but Norman was very tough – sort of determined that he would be able to control the narrative."

Hopkins was sceptical about Foster's expectation that he could dictate the journalist's work. She was wrong; he got his way.

"He just had this – slightly un-English, in a funny sort of way – determination, that as a younger architect I was struck by."

"He understands the client"

At times, Foster has been prepared to resist compromising on his ambition for the sake of others' feelings.

For instance, Su Rogers reports that he was transparent about wanting to leave Team 4 because he no longer wanted to work with her as an unqualified architect.

In the past, Foster has sometimes been portrayed as a cold personality, most searingly in a thinly veiled parody in Philip Kerr's 1995 novel Gridiron, as the architect of a highly technical building that becomes sentient and commits mass murder.

He has also been depicted as cutting an unnerving presence on the Foster + Partners office floor.

Nevertheless, those who have interacted with Foster over the years have positive things to say about him.

"He is still the engaging, sharp, thoughtful person he was when we were students together at Yale 60-plus years ago," said Abbott, who remains a friend.

One of Foster's key attributes on his route to success has been his skill as a communicator.

"He's fantastic at talking to people," said Shuttleworth. "He's very good at selling ideas."

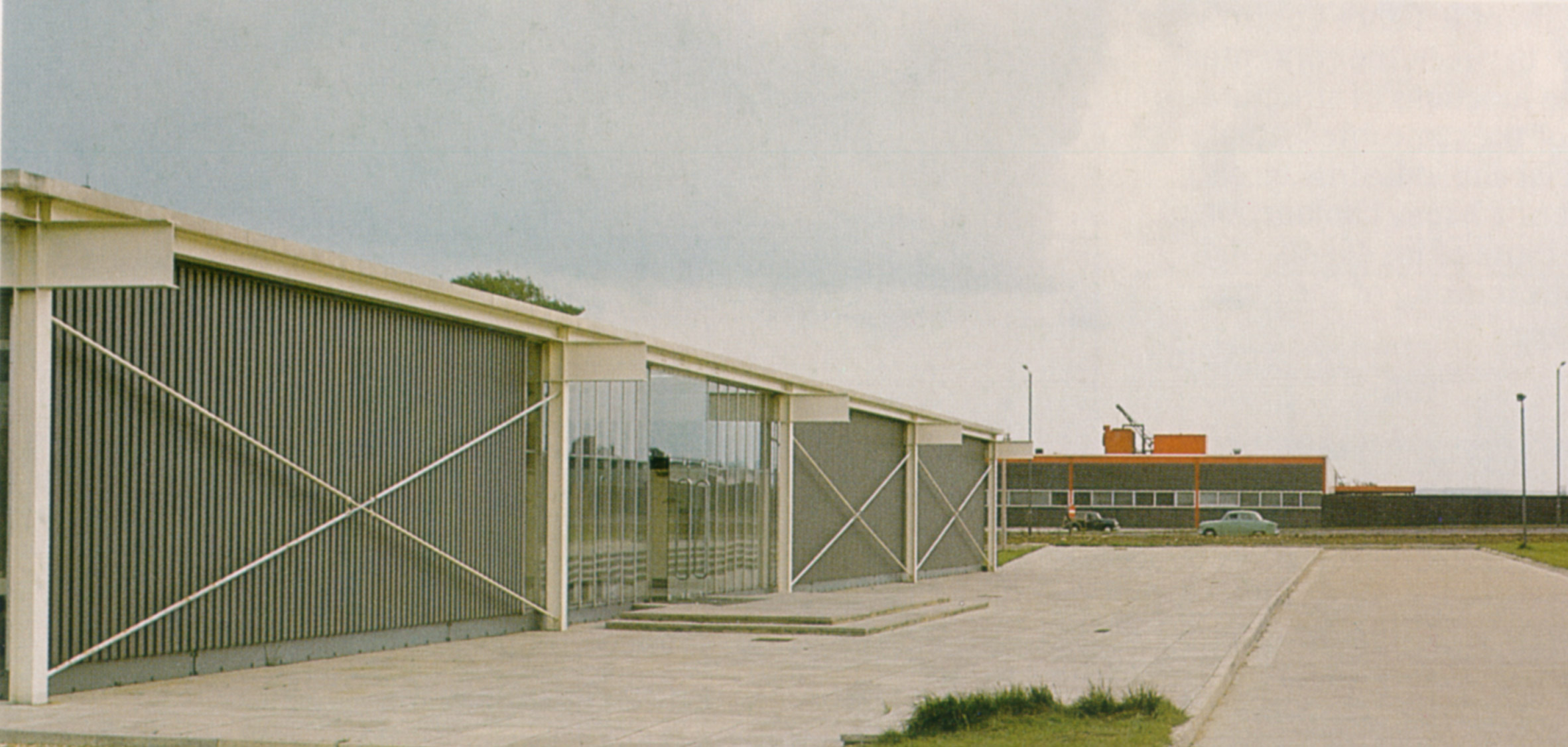

Even in the Team 4 days, Su Rogers says, Foster was "very, very good at getting clients". It was Foster who landed the group's biggest and final project, the Reliance Control factory in Swindon, completed in 1967.

In 2012, a series of videos emerged showing Foster pitching for a major skyscraper project at 425 Park Avenue in New York, in competition with other world-leading architects – Richard Rogers, Zaha Hadid and Rem Koolhaas. Foster + Partners' 425 Park Avenue was completed in 2022.

Writing about the pitches, Guardian architecture critic Oliver Wainwright remarked that "it is not hard to see why Foster so often triumphs".

"Norman was the only one who talked about them as a client," Shuttleworth said of the clips. "He understands the client, he tries to talk to them about their issues, he dresses like them."

"That is different – not many architects do that."

This ability has enabled Foster to consistently convince the world's biggest business leaders to work with his firm, including Jobs, Michael Bloomberg and JPMorgan Chase CEO Jamie Dimon.

Also, unusually for an architect, Foster is a shrewd businessman himself.

From the very first days of running his own studio, Rogers says, he was "very good at investing money in things which were going to grow to support the architecture practice".

He and his long-serving Foster + Partners leaders have demonstrated an uncanny ability to identify where lucrative projects can be landed – from the booming financial industry in the 1980s to Apple in the 2000s, and with 40 per cent of the firm's revenue now generated in the Middle East.

This has sometimes been associated with criticisms, particularly over the ecological impact of some Foster + Partners projects or the regimes it works with. It is currently working on a secretive plan for a two-kilometre-tall skyscraper in Saudi Arabia, among many other projects in the country.

"He's clearly an extraordinary business person, to be able to sniff out where the commissions are going to come from and where is going to be the focus," said Owen Hopkins.

"He's a force of nature"

Whatever the significance of his savviness, Owen Hopkins and others contend that Foster's ability to ensure his studio keeps turning out effective buildings is even more striking.

"There is clearly the desire to be successful," said the historian. "But I don't want to do a disservice to the work, which at its best is brilliant."

"Maybe the quality is not always as high as the best projects, although it would be hard to see how that would be possible, because the best are really good, and even a mediocre Foster building is still much better than most, I think it's fair to say."

Dezeen asked Foster for his own thoughts on how his firm manages to stay so prolific while maintaining critical acclaim.

In an extensive answer – published in full below – he pointed to Foster + Partners' unusual organisational structure.

The firm is broken into six studios, each able to compete for any project type anywhere in the world. These are able to draw on technical support from an army of specialist staff. All projects are then reviewed by a design board, chaired by Foster.

Among other significant factors, he argued, is "a deep-rooted respect for those who commission us – the budget and the timeline".

Frédéric Migayrou, a professor at The Bartlett School of Architecture who curated a major exhibition on Foster's work in 2023, is adamant that the real secret to the architect's success is simply his design talent and the adaptability of his approach.

He argues that Foster's unwavering conception of buildings, influenced by the American inventor Richard Buckminster Fuller, as systems in which technology and the physical environment should work together in perfect, efficient harmony, has been the defining architectural philosophy of our age.

"It changed completely the vision of architecture," Migayrou told Dezeen. "You can say what you want about the person – his involvement in economy and power – but he created really a moment of disturbance which is unique in the history of architecture at this period."

Put another way, Foster has been the perfect architect for his era.

"It's a really interesting but incredibly difficult question to try to answer: why has he got this pre-eminent position, and how has he managed to keep going?" said Owen Hopkins.

"It's quite extraordinary. He's a force of nature, isn't he, really."

"Norman is more than an architect," said Abbott. "And I don't know the word. There's a word knocking around called a futurist – that's maybe it."

"I'm amazed at the things he's doing. And it's not ending."

Read on for Foster's own take on why he's been so successful:

Dezeen: What makes you different to other architects? What is it about your approach that has allowed Foster + Partners to experience sustained commercial success over many years with minimal compromises on design quality?

Norman Foster: Easier for others to answer, but I will try. I think there are several reasons.

First, going back in time, the practice started in the 1960s with a systems approach to design. In this philosophy, the systems of structure, enclosure and services, to name the key ones, are seen as being interconnected. In the pursuit of optimising their integration, there is the potential to do more with less – a better quality of life, more joy, higher performance, a greater value with less redundancy, mass, weight and energy.

Technology is seen as a means to social ends, and from the birth of the practice, its projects have encouraged conservation of energy and nature, recycling of waste, harvesting of energy, and the benefits of natural light and views.

As a student of architecture at Manchester University in the 1950s, I had a parallel interest in studying cities and public spaces. Over the years, this has evolved into an embrace of urban design and infrastructure, which has also had beneficial effects on the design of individual buildings.

At Yale University in the masters course, I challenged the assumption that an architect designs in isolation from engineers. By working alongside an engineer at the formative stage of the design, I had more knowledge of the creative generators and was more empowered as a designer.

This experience has shaped the practices that followed – the first partner beyond the two founding architects of Foster Associates in 1967 was an environmental engineer and currently there are 226 engineers in the practice. Incidentally, the systems approach that I noted at the outset is only possible when all the key disciplines are creatively involved from the outset.

All of this is by way of background, but it brings us to the three pillars of the practice, which have served us for several decades.

First, is the studio system, which breaks down the scale of the architectural practice currently into six studios, each with its head. Counterintuitively, any studio can compete for any kind of project, anywhere in the world – there is no breakdown geographically or by building type. Studios are encouraged to partner with each other.

Second is the Design Board, which I chair, and which reviews all projects – it has full-time core members as well as Studio Heads.

Third are the Specialist Groups, which provide a wide diversity of skills – these currently number 500 – and are accessed by the studios. Some of these groups also provide independent services.

What are the unwritten codes and attitudes that permeate the practice and have the potential to make it "different"? In no particular order, the organisation of the practice is hierarchical – in shape a table topped pyramid with some 250 partners – but the creative process is flat-lined – everyone is encouraged to contribute.

Then there is a deep-rooted respect for those who commission us, the budget and the timeline. In addition, everyone is encouraged to go where the action of making takes place – the factories and the building sites.

Finally, there is no "front of house" – hardly any meeting rooms as such. Almost all the action, with a huge number of daily visitors, takes place in the open. I have never had an office – I move around constantly, and the only time I sit down is at a round conference table at the end of the studio, which is mostly shared in design meetings.

The main image is by Simon Volt. Photos by Foster + Partners, Ian Lambot, Ken Kirkwood, Rudi Meisel, Pablo Gómez Ogando, Ben Dreith and Viktor Forgacs.

Dezeen In Depth

If you enjoy reading Dezeen's interviews, opinions and features, subscribe to Dezeen In Depth. Sent on the last Friday of each month, this newsletter provides a single place to read about the design and architecture stories behind the headlines.

The post How Norman Foster became the most successful architect in history appeared first on Dezeen.