"Art deco designers shared a desire for an aesthetic appropriate for a modern world"

One hundred years ago this April, the Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs introduced art deco to the world. To kick off our Art Deco Centenary series, Kathleen Murphy Skolnik gives an overview of the style.

Art deco, the name now given to the modern, exuberant decorative movement of the 1920s and '30s, is a term that defies definition.

Although commonly associated with such features as stylisation, verticality, geometric forms and sunburst, fountain and floral motifs, its visual manifestations can vary widely, ranging from the faceted crown of New York's Chrysler Building to the simple, streamlined forms of Greyhound bus stations, and from the elegant lacquered masterpieces of Jean Dunand, to the colourful ceramics of British designer Clarice Cliff, to simple bakelite radios.

The diverse manifestations of art deco mirror the diversity of the interwar years, a time that encompassed both the great financial prosperity of the 1920s and the extreme economic hardship of the Great Depression.

It was a time of democracy in the United States and many European nations but a time of totalitarianism in other countries of Europe. And it was a time of greater independence for women, who were bobbing their hair and shortening their skirts, but more importantly exercising their right to vote and entering the workforce.

The wide diversity in art deco designs also reflects the many different and sometimes conflicting 19th- and early-20th-century artistic styles and design movements that contributed to its emergence.

The most commonly cited are cubism with its angular, fractured forms, exoticism with its fascination with distant times and places like ancient Egypt and Mesoamerica, and the ballet russe with its vibrantly coloured costume and set designs. But there were many others, including art nouveau, the Glasgow school, the Vienna secession, German expressionism, the Amsterdam school, futurism, fauvism, Russian constructivism, the Bauhaus, machine aesthetics, and aerodynamic principles.

The variability in the appearance of art deco designs has led scholars to characterise it as a movement, spirit, idiom, or approach to design rather than a distinctive style. As Jared Goss, an independent scholar and former associate curator in the department of modern and contemporary art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, points out in his 2014 book French Art Deco, style implies "specific shared characteristics" and art deco's diversity "precludes conceptual unity".

Art deco designers shared a common desire to create a new aesthetic appropriate for a modern industrialised world, but the way in which this impulse was expressed visually could differ widely.

The phrase "art deco" was not in use at the time of the movement's peak popularity in the 1920s and '30s. This designation was not applied in its current context until 1968, when it was introduced by the British author and critic Bevis Hillier in his book Art Deco of the 20s and 30s.

But its derivation can be traced to a decorative arts exposition that occurred decades earlier: the Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes, which opened in Paris in 1925. Art deco is based on the French term for decorative arts – arts décoratifs – found in the exposition's name.

Some sources cite the 1925 Paris exposition as the beginning or the birth of art deco, but that's rather misleading. The exposition was, however, unquestionably a defining moment in the evolution of the art deco movement.

It brought this new approach to design to the attention of a worldwide audience and led to its dispersal on an international scale to sites as distant as Argentina, Brazil, Australia, India, and South Africa.

But what we now call art deco had existed for years, even decades, prior to 1925. For example, the Théâtre des Champs-Élysée, considered to be the first art deco building in Paris, opened in 1913, more than 10 years before the Paris exposition.

The main purpose of the exposition was to reassert France's longstanding reputation as a leader in the production of luxury goods and the authority on matters of taste, a reputation being challenged in the early 20th century by designers in other European countries, primarily Germany and Austria.

Unlike earlier international expositions that focused on scientific innovations and industrial advances, this one was devoted exclusively to the decorative arts and more specifically to modern decorative arts.

Invitations to participate came with this stipulation: "Works admitted to the exhibition must show new inspiration and real originality... reproductions, imitations and counterfeits of ancient styles will be strictly prohibited."

The French pavilions, which occupied two-thirds of the exposition grounds, were devoted primarily to specific designers and manufacturers, French industries, and artists' associations. The exteriors tended toward elegance and refinement, like the Hôtel d'un Collectionneur (Home of a Collector), the pavilion of the French furniture designer and ensemblier, or interior designer, Émile Jacques Ruhlmann with its modernized classical design.

The Grand Salon of the Une Ambassade Français (French Embassy Pavilion), which represented an imaginary embassy in an unidentified foreign capital, was a modern interpretation of traditional 18th- and 19th-century French forms. In contrast, Jean Dunand's lacquered fumoir, or smoking room, tended toward the more avant garde.

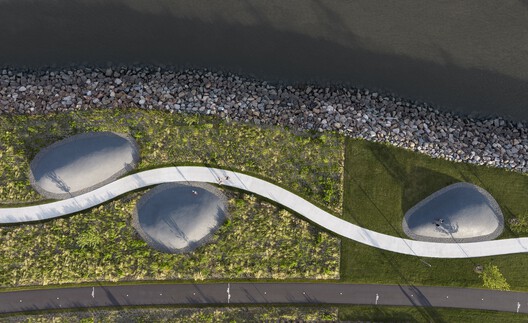

In contrast to the modernized classicism of the French pavilions, the foreign pavilions were more varied in their designs. The small Swedish pavilion showed a strong classical influence with its slender Ionic columns. The Japanese pavilion incorporated traditional materials like straw and wood. The striking pavilion of the Soviet Union, which housed a model of a Socialist Worker's club, was a dynamic design composed of two transparent triangles jointed by a diagonal staircase.

Following the exposition, designers and architects embraced art deco with the flamboyant interiors, distinctive architecture and stylised products – along with cars, trains and ships, becoming synonymous with the 1930s.

World war two necessitated a move away from the lavish ornamentation and costly materials, such as lacquer and exotic woods, favoured by art deco designers. Designs became more streamlined as opulence gave way to restraint.

By the war's end, modernism, with its clean lines and sparse embellishments, was on the rise and art deco went into hibernation for about two decades until Hillier's 1968 book once again brought it into the spotlight. Following the book's publication, two major art deco exhibitions took place in the United States, including one at the Minneapolis Institute of Arts that featured nearly 1,500 objects, and preservation movements began to emerge.

In 1991 the first World Congress on Art Deco took place in Miami Beach, Florida. Now a biennial event, the world congress brings together art deco scholars, collectors, and enthusiasts from around the world to exchange and promote information relevant to the understanding and preservation of art deco.

Today, 100 years after the 1925 Paris exposition, art deco continues to captivate and delight. Museum exhibitions showcasing art deco are attracting sizeable audiences, and art deco designs sold at auction are commanding record-breaking prices. And this October the art deco world will celebrate the lasting legacy of the exposition when the 17th world congress convenes in Paris.

Kathleen Murphy Skolnik is an art and architecture historian, based at Roosevelt University in Chicago. She is the co-author of The Art Deco Murals of Hildreth Meière and a contributor to Art Deco Chicago: Designing Modern America. She was previously editor of the Chicago Art Deco Society Magazine and currently sits on the advisory board of the Art Deco Society of New York and the board of the International Hildreth Meière Association.

Art Deco Centenary

This article is part of Dezeen's Art Deco Centenary series, which explores art deco architecture and design 100 years on from the "arts décoratifs" exposition in Paris that later gave the style its name.

The post "Art deco designers shared a desire for an aesthetic appropriate for a modern world" appeared first on Dezeen.