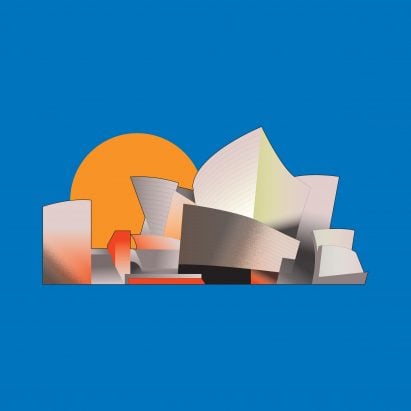

Frank Gehry's Walt Disney Concert Hall was the most significant building of 2003

Next up in our 21st-Century Architecture: 25 Years 25 Buildings is Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles by Gehry Partners, an icon of deconstructivism. Disney Hall is perhaps the most famous building by Frank Gehry who, despite being Toronto-born, is one of, if not the most, famous living American architects. Its completion in 2003, The post Frank Gehry's Walt Disney Concert Hall was the most significant building of 2003 appeared first on Dezeen.

Next up in our 21st-Century Architecture: 25 Years 25 Buildings is Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles by Gehry Partners, an icon of deconstructivism.

Disney Hall is perhaps the most famous building by Frank Gehry who, despite being Toronto-born, is one of, if not the most, famous living American architects.

Its completion in 2003, after more than 15 years of stops and starts, marked the return of Frank Gehry's rising architectural stardom to his adopted home city of Los Angeles, where the architect had been living since the 1940s.

With its crescendo of complex stainless steel panels, the symphony hall is considered an iconic example of deconstructivism – a movement that tended towards asymmetrical forms.

Though Gehry himself eschewed being labelled a deconstructivist, his work brought global attention to the style.

In the early 21st century Gehry designed countless projects, but this building's significance also stems from the near-ubiquitous influence of the Disney media empire's role in contemporary culture, though the building is owned by LA county's Music Center.

A relatively rectilinear concert hall, which hosts the Los Angeles Philharmonic symphony, sits tucked inside of the imposing metal shell.

At its heart is a sculptural organ made up of functional, asymmetrical tubes created in collaboration with tonal designer Manuel Rosales and organ builder Caspar Glatter-Götz.

The interior was clad with Douglas fir, chosen for its "psychological effect" according to Gehry, who worked with Yasuhisa Toyota of Japanese firm Nagata Acoustics to design the auditorium for sound.

Gehry said that he designed the building "inside out", first focusing on the music hall and then moving outwards to the now-famous external stainless steel shell, which has been described alternatively as resembling petals or sails.

The building was intended to be a democratised version of a private arts complex, with Gehry stating he intended the Disney Hall to be a "living room for the city" with its lobby accessible to the public.

The concert hall itself extends this sense of democratisation. Informed by Hans Scharoun's Berlin Philharmonie hall, the hall holds a relatively modest 2,200 people, the terraced, vineyard-style hall lacks columns and boxes.

"There is no obvious hierarchy," wrote critic Paul Goldberger in the New Yorker in 2003.

Disney Hall was originally commissioned in 1987 by Lillian Disney, the widow of American animator Walt Disney, who donated $50 million (£38.5 million) to the project in memory of her late husband.

With this seed money, a block of county-owned land on Grand Avenue was set aside and government funds were allocated to begin work on construction.

The most gallant building you are ever likely to see Herbert Muschamp in the New York Times

That a deconstructivist design was selected for such a large, high-profile structure in an American city may have come as a surprise, especially in the context of Downtown Los Angeles with its modernist pavilions and glass-clad highrises.

However, Disney as a company had already chosen avant-garde designs with its selection of postmodern American architect Michael Graves.

Lillian Disney herself was not immediately sold on the design but gave Gehry leeway. In return, the architect included a number of homages to her tastes, including the floral patterns on the seats of the auditorium and a garden that included a sculpture made of pieces of Delft pottery.

The project progressed slowly and by 1995 only the foundations had been built. In 1997 the project received a boost with another round of funding after a campaign by American businessman Eli Broad and then-Los Angeles mayor Richard Riordan.

When the building finally opened in 2003 it was well received – by the clients, concert-going community and architecture critics.

At the time of its opening, New York Times architecture critic Herbert Muschamp wrote that Disney Hall was the "most gallant building you are ever likely to see".

The building is often referenced in the same breath as the titanium-clad Guggenheim Museum Bilbao – a building that was credited for the artistic and economic upturn in the small Spanish city – a phenomenon named the "Bilbao effect".

However, the funding and plans for Disney Hall had been hatched nearly a decade before Bilbao's completion.

It is a serene, ennobling building that will give people in this city of private places a new sense of the pleasures of public space Paul Golberger in the New Yorker

The success of Bilbao would ultimately play a role in shifts in the design. For example, Gehry originally intended for the facade to be clad in stone for its ability to create a soft glow at night.

Gehry said he thought the metal would make the building look "like a cheap refrigerator" at night, eventually relenting.

During the day though, it shone – perhaps too much. Just a year after it completed the facade had to be sanded down after the glare from its reflection was considered a hazard to drivers.

Despite the similarities with Bilbao, the architecture of Disney Hall became iconic in its own right and represented Gehry's indelible mark on Los Angeles.

"The building is a fantastic piece of architecture – assured and vibrant and worth waiting for," wrote LA Times critic Christopher Hawthorne. "It has its own personality, instead of being anything close to a Bilbao rehash."

At the opening, mayor Riordan said that the building was a "symbol" of Los Angeles "finally having a downtown".

Whether or not the structure inaugurated a Bilbao Effect in depressed Downtown Los Angeles remains to be seen – Gehry himself thought the structure should go elsewhere.

Development in the area has continued, if slowly, with a pair of mixed-use towers by Gehry and the Diller Scofidio + Renfro-designed The Broad museum rising in the vicinity in the decades since. Gehry is also at work on the Colburn School for music nearby.

Goldberger wrote in 2003 that he wouldn't "bet" on the building jumpstarting renewed growth in the area, but also that it "doesn't matter".

"It is a serene, ennobling building that will give people in this city of private places a new sense of the pleasures of public space."

The Disney and Gehry names together make this structure beyond emblematic of this century, and the question of sculptural architecture's role in the American city continues to be worked out in the petal-like shadows of Disney Hall.

Did we get it right? Was Frank Gehry's Walt Disney Concert Hall the most significant building completed in 2003? Let us know in the comments. We will be running a poll once all 25 buildings are revealed to determine the most significant building of the 21st century so far.

This article is part of Dezeen's 21st-Century Architecture: 25 Years 25 Buildings series, which looks at the most significant architecture of the 21st century so far. For the series, we have selected the most influential buildings from each of the first 25 years of the century.

The illustration is by Jack Bedford.

21st-Century Architecture: 25 Years 25 Buildings

2000: Tate Modern by Herzog & de Meuron

2001: Gando Primary School by Diébédo Francis Kéré

2002: Bergisel Ski Jump by Zaha Hadid

2003: Walt Disney Concert Hall by Frank Gehry

This list will be updated as the series progresses.

The post Frank Gehry's Walt Disney Concert Hall was the most significant building of 2003 appeared first on Dezeen.

What's Your Reaction?